The Inner Life of the American Communist

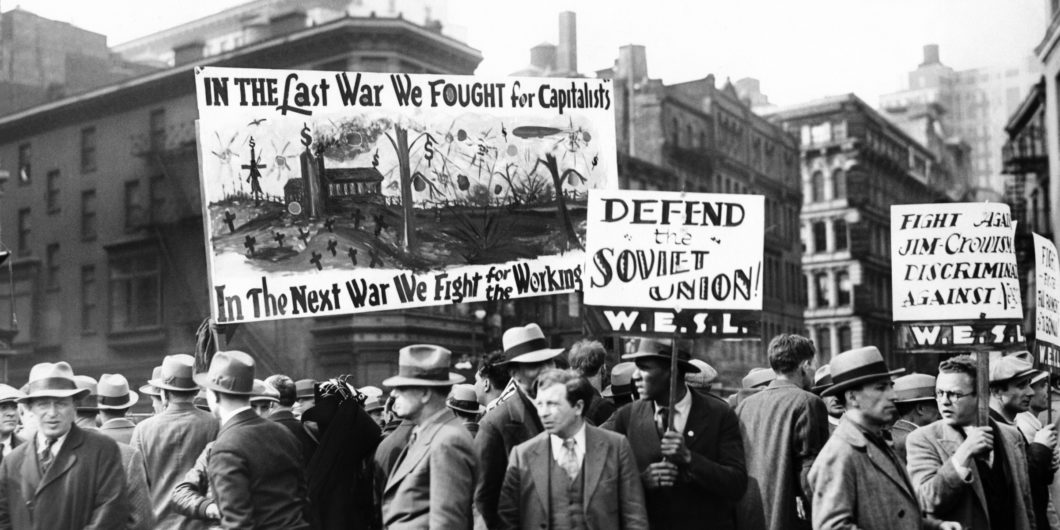

The title of Vivian Gornick’s 2020 re-release of her 1977 book, The Romance of American Communism, isn’t quite right. It would be better titled as “The Romance of the American Communist Party.” To be sure, ideology and the Party overlap, significantly. But it is with the Party in particular that the romances described in the book are had—and with which they end. These romances mostly end bitterly, with the destruction of the Party’s living spirit in 1956. It died on February 25, 1956 to be exact, when Khrushchev delivered his “Secret Speech” to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union denouncing “The Cult of Personality and Its Consequences” under Stalin. The speech devastated the American Communist Party. It never recovered.

Gornick, a “red-diaper baby” raised in the communist hothouse of New York City in the 1930s and 1940s, interviewed scores of former Communists (and some continuing communists) active in the Party during the Party’s heyday during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. This is not a history of the Party, however, except indirectly. Gornick interrogates the inner lives of these Communists. What they felt, what they experienced. What motivated their membership and their work for the Party. Finally, why the romance ended; why they left the Party, or why they were kicked out.

Despite the rarefied focus on members of the Communist Party during a period decades old when originally published, and now over half a century ago, the focus on the inner lives and experiences of Communist Party members makes it a book more generally about humanity. By that I don’t mean the book evokes the humanity of these Communists in a sympathetic way, although Gornick intends her book to provide a sympathetic treatment.

Regardless of her apparent intentions, the painful end of the romance dominates the book from start to finish, and this is true even for Gornick herself. Here we see the full continuum of human response to having made a spectacularly bad choice. These responses are not pretty, despite Gornick incessantly describing the former Communists as “beautiful” or “bright-eyed” or “impressive” or imbued with an “inner illumination.”

Few of her subjects can flat out admit to Gornick—nor, apparently, to themselves—that they made a terrible choice in joining the Party. Romance offers a series of 40-some case studies in self-deception. Gornick’s subjects rationalize, justify, and flatter themselves in an effort to avoid confronting this ugly truth. They cannot overcome the tremendous waste of their lives, and the lives of others, and this includes Gornick herself.

Like real people, they don’t necessarily learn from their experience or always end up any wiser. In this their lives are like the lives of almost everyone else in that it is hard for most of us to find regular, television-style character development, illumination, or growth. But the lives of these ideologues present some startling failures in self-realization and a striking absence of self-honesty. There is certainly too little deep reflection about the link between ideology and Party that produced these results.

Despite how the end overawes the beginning and the middle, it would be wrong to read the end into the beginning and the middle. Gornick and her subjects open an otherwise closed door to us today on Communism and the Communist Party from the 1930s to the mid-1950s. It’s hard to understand the experience today. We don’t understand how all-consuming the Party was to the people involved, and also to many who opposed it. We see the experience through the lens of the gentle mockery of the Coen brothers’ Hollywood Marxist study group in Hail Caesar. (Which, incidentally, has Gornick’s subjects dead to rights. The Coens simply needed to portray the oh-so-earnest study group to mock it.)

I expect Gornick highlights the theme of communism’s romance because the alternative theme of Communism’s religious-like dimension is better trodden, if perhaps less understood in America’s increasingly post-Christian society. That the Party called for faith and sacrifice and that Marxism provides an eschatology of the post-revolutionary world-to-come are all well known aspects of Communist belief. While not dwelling on the analogy, Gornick’s subjects can’t help but observe the analogy in their experience as well, with the focus on the institutional parallel between Church and Party:

With the exception of the church and its myths and legends, there was no agency in the world so capable of making men feel the earth and the people upon it than the Communist Party.

Beyond the obvious, Gornick’s personal histories highlight other, less obvious, analogies to Christian religious experience. One of the Gospels’ seldom-emphasized themes is the restoration of the faithful’s full humanity through the second Adam, Jesus Christ. Gornick’s subjects repeatedly report that their conversion to Communism restored to them a true sense of their full humanity.

Everything happened so quick then. . . . I saw it all at once. And all at once, I saw, and I could hardly believe this, there was a way out for me. . . . I saw that being a worker was literally slavery, and that the slavery came from being a dumb animal hitched forever to the machine, and this idea of us as a class relieved the slavery, gave you a way to fight, gave you a way to become a human being.

Another subject put it this way:

You know, forty-six years have gone by since that time. That’s a lot of years. I spent thirty of them in the Party, and now sixteen out of the Party. . . . But you know? They can never equal each other. Those years in the Party, they made me a human being. Nothing else did. Nothing else ever could. The Communist Party did a lot of terrible things, but one thing I gotta give it; it took raw American clay, and made a thinking human being out of it.

So, too, the Party provided an intense feeling of community, of solidarity; an echo of the ontological unity of the deep Church, individual people being united to each another in the One Body of Christ. One female subject observed:

Of all the emotions I’ve known in life, nothing compares with the emotion of total comradeship I knew among the fruit pickers in the [Nineteen]Thirties, nothing else has ever made me feel as alive, as coherent. It was for that, for the memory of that time, that I hung on.

Or Gornick herself:

It was the Party that brought to astonishing life the kind of comradeship that makes swell in men and women the deepest sense of their own humanness, allowing them to love themselves through the act of loving others. . . .

You were, if you were there, in the presence of one of the most amazing of humanizing processes: that process whereby one emerges by merging. . . . [Y]ou were in the presence of the socializing emotion, that emotion whose operating force is such that men and women feel themselves not through that which composes their own unique, individual selves but rather through that which composes the shared, irreducible self.

And yet the Party was an idol, ultimately communicating death rather than life. The Party, Gornick writes, was at first “compellingly humanizing” yet turned “compellingly dehumanizing.” One of Gornick’s subjects tells her:

I must say I lost more than I gained from being a Communist. My inability to live among people, to live inside my own skin, is the great reality for me now. . . . Somehow . . . that doesn’t seem quite right. Having lived my life in the service of the humane ideal, it seems to me I should feel more human now not less so. And this is not the case, not the case at all.

Another ex-Communist says:

I am bound to [the Party] by ties stronger than love or hate. . . . To hate it, to deny it, to turn on it is to wipe myself out. That I cannot do. . . . In some sense it’s like a walk around with this gaping wound inside me, holding myself together. But I do it. I walk around and hold myself together.

The Party ultimately ministered isolation rather than community, injustice rather than justice with the defense of Stalin and the show trials both in the Soviet Union and Party trials in the U.S., then disillusion and dissolution. Almost all of Gornick’s subjects discuss growing doubts and unease with the Party, even long before the Khrushchev report. And finally, with the report itself, “Overnight, the affective life of the Communist Party in this country came to an end.”

So what lessons? A part of me resists drawing more-general lessons. The experiences which Gornick reports are compelling, lives inspired and consumed by an all-encompassing ideology, lives devoted to serving the Party, and then all of that suddenly crushed. They are just people coming to grips with having made a breathtakingly bad decision, both for themselves and for others.

Yet perhaps implications exist for us as well. Perhaps cautionary lessons of seeking solidarity through worldly institutions, whether that institution is called the Party, or whether that institution is called the nation. Yet Gornick offers little by way of implication for today’s radical Left moment relative to yesterday’s, because without the Party there can be no comparison. There was a deep ideological faith inherent in the experience of the Communist Party from 1919 to 1954. That deep faith might continue in individuals today. Yet the old faith was incarnated almost solely in and around the Party. This consigns the personal histories in Gornick’s book to the past. A tragic past for the subjects of her book, no matter whether they admit it to themselves, or to Gornick.