The Living Constitution’s Illimitable Government

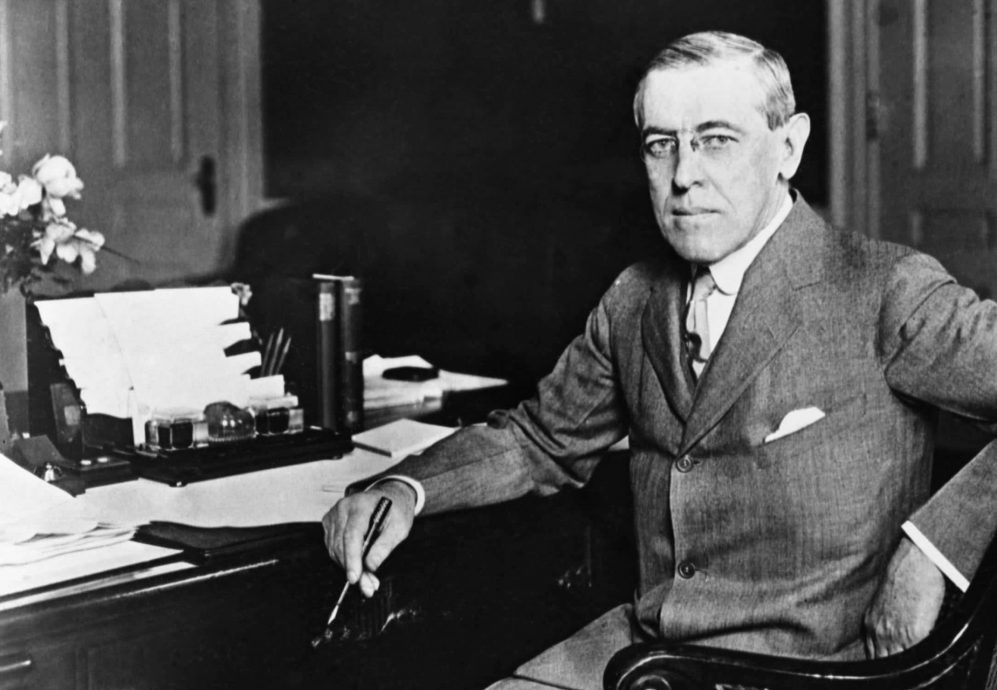

“All that progressives ask or desire is permission—in an era when ‘development,’ ‘evolution,’ is the scientific word—to interpret the Constitution according to the Darwinian principle.”

Woodrow Wilson, “What Is Progress?”

That Wilson and his progressive epigones got what they wanted is too plain to permit of serious doubt. Those disinclined to accept such matters on faith need look no further than Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 landmark case that legitimated same-sex marriage. That case was decided in the court of public opinion before it was decided in the court of last resort, and but for that earlier pronouncement, the latter would not have been reached. To frame that differently, it is only because public opinion shifted appreciably in favor of same-sex marriage that the Supreme Court announced that a right to it was now fundamental.

Clearly, Obergefell could not have been handed down in an earlier century. But it was not the Constitution that changed in that time, at least not with regard to the matter at hand. What changed was the opinion of the public. And the Court, cognizant of that change, updated the Constitution to reflect that societal shift and canonize a right that the document never contemplated. To return to the progressives’ opening supplication: permission granted.

Wilson’s gripe with the Framer’s Constitution is that it was ill-conceived; or, to be more charitable, it was well-conceived given the century that they inhabited, but the wisdom of their day was superseded by the wisdom of a later one. Such is the implacability of progress: it forgives no fallacy and confines every age to obsolescence. For Wilson, “those fathers of the nation” viewed government as the scientists of their age viewed nature: mechanistically. “Politics in their thought was a variety of mechanics.” But governments are not machines; they are living things. Accountable to Darwin, not to Newton, they obey the laws of life, not mechanics. The Framer’s system of checks and balances is fatal to government, for “no living thing can have its organs offset against each other, as checks, and live.” Instead of being allowed to adapt to circumstances and evolve, as all life—if it is to persist—must, the Framer’s constitutional order is fated to atrophy and perish.

To be fair, unlike the Decalogue, the Constitution is not set in stone. The men who gathered in the Pennsylvania State House in the summer of 1787 were merely that—mortals, not demigods as Jefferson memorably portrayed them. Well aware of their mortality and fallibility, they proffered a foundational document that could be amended to reflect the changing needs and values of the American people. Admittedly, the Constitution does not readily accommodate amendation. A mere 27 amendments have been affixed to it over two and a third centuries, a number that appears even more modest when one takes into account that the first ten were added straightaway and the last had been penned and proposed along with the first. But that resistance to change is integral to the Constitution’s raison d’être, which Wilson misapprehended. The alternative that Wilson propounded is false. The choice is not between a living constitution and a moribund one. It is the living constitution that is menaced with death for the very reason that all that lives dies. The alternative, then, to Wilson’s living constitution is an enduring one. That is what the Founding Fathers bequeathed to their posterity—a Constitution designed not to evolve, but to endure.

John Marshall, that lone justice fit to be called a statesman, grasped the nature and purpose of this design. Pace Wilson, the Constitution was not some static document repugnant to change, but nor was it an abstruse palimpsest that could be interpreted capriciously per the whims of its expositors. As Marshall put it in McCulloch v. Maryland, the landmark case that established the constitutionality of the national bank and, more consequentially, the elasticity of the Necessary and Proper Clause, the Constitution is “intended to endure for ages to come.” That intention can be gleaned, in part, from the broadness of its brushstrokes. Were the Framers to enumerate every legitimate power that the government possesses, as well as the proper means for its execution, not only would the document “partake of the prolixity of a legal code [that] could scarcely be embraced by the human mind,” but it also would be rendered obsolete from one age to the next. It is thanks to the Framers’ genius, not Wilson’s, that America boasts the oldest extant written constitution the world over.

Once it becomes permissible to update the Constitution, not by amending it, but by reinterpreting it (whether in the courts of law or that of public opinion), the foundational law loses its force and meaning.

Its nature and purpose also can be gleaned from the fact that the Constitution was written at all. And here, as before, Marshall’s sagacity eclipses Wilson’s. Written constitutionalism is a relatively recent development, one that largely can be traced back to the late eighteenth century. One need not be conversant in history to safely infer that given this late date, political regimes got on just fine without written constitutions. Why, then, did the Americans feel impelled to constitute themselves in writing? Marshall’s answer, put forward in Marbury v. Madison, is that “all those who have framed written constitutions contemplate them as forming the fundamental and paramount law of the nation.” They are foundational laws that not only constitute governments, but spell out their ends (to secure the blessings of liberty) and limit their powers (the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it). And they are intended to do so in perpetuity. Written constitutions make no sense if the governments they constitute can contravene the limitations imposed on them. They would, in Marshall’s words, be but “absurd attempts, on the part of the people, to limit a power, in its own nature, illimitable.”

A living constitution cannot be squared with a written one for the generative principle of the former controverts the animating purpose of the latter. Once it becomes permissible to update the Constitution, not by amending it, but by reinterpreting it (whether in the courts of law or that of public opinion), the foundational law loses its force and meaning. The ligatures that constrain the state become attenuated and a government of laws slowly mutates into a government of men. A governmental system that does not check and balance itself is bound to become unchecked and unbalanced. This has less to do with the nature of the system than the nature of those who run it.

To paraphrase Madison, human nature is reflected not only in the need for government, but in the need—if liberty is to be secured—for a certain kind of government: namely one that is enabled to control the governed and obliged to control itself. In the absence of such restraints, governments will further and further extend their reach for that is what governments—or rather, the persons who comprise them—do. As Hamilton observed, “a fondness for power is implanted in most men, and it is natural to abuse it when acquired.” Hardly in need of validation, the veracity of Hamilton’s insight is confirmed by governmental (mis)behavior in the time of COVID, a time that has witnessed an unprecedentedly prolonged and widespread curtailment of civil liberties. The acquiescence with which too many Americans have exchanged their liberty for security suggests that they are deserving of neither.

Before he became the nation’s chief executive, Wilson seemed to espouse the wisdom of the Framers. In a speech delivered to the Commercial Club of Chicago in March of 1908, he decried “the perfect mania for regulation that has taken hold of us.” If left unchecked, that mania would pave the way for despotism, the injustice of which would greatly exceed whatever private injustices might materialize in an unregulated market. “I can resist my neighbor,” said Wilson, “but I cannot resist the government; and when the government is made strong against me and interferes in everything I attempt to do, then my life is the life of a man enslaved.”

That is the sort of sentiment that would compel a man to preserve, protect, and defend a written constitution; a sentiment, alas, that Wilson later spurned when he advocated for a constitution that answers to Darwin and not to Newton. It is telling and hardly a coincidence that in the name of progress, the living constitution sanctioned the forced sterilization of tens of thousands of people in the early part of the twentieth century. Those who shudder at the Progressive’s abuse of power in the name of science, but applaud the government’s present abuse of power in the same name, apprehend history and the disposition of the beings who make it poorly.

The written constitution was designed to forestall such gross offenses. The extent to which the Founders intended to limit the government that they framed is nicely illustrated by Hamilton in his argument against the need for a bill of rights. Hamilton, the arch-federalist who was (wrongly) suspected of being a monarchist and who advocated that the government be given “a liberal latitude” with regard to the exercise of its constitutional powers, thought a bill of rights not only superfluous, but dangerous, for it “would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and, on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do?”

Notwithstanding the logic of Hamilton’s argument, it did little to allay the fears of those at the time of the founding who felt that in the absence of further guarantees, their sacred liberties would not enjoy the security they duly deserved. And so, a bill of rights devised to protect the people from a government that is naturally inclined to arrogate to itself more and more power was promptly appended to the Constitution. If it was a piece of folly to reason that the government would never exercise powers it was not granted, there is no less folly in the view that fundamental rights will be preserved when the written constitution is replaced with a living one. When interpreted in the light of current exigencies and fashions, the state can exercise powers it does not constitutionally have and enshrine rights the people do not constitutionally possess (or for that matter, deprive them of ones that they do). That danger may not trouble the sleep of those who find themselves in line with the reigning orthodoxies, but power changes hands and the orthodoxies of today are the heterodoxies of the morrow. Fundamental rights and principles ought not to be dictated by and dependent upon the day’s trendy and transitory conceits. That is a verity that the Framers grasped, one that eludes far too many today.

At this time, there is much hand-wringing about the possibility of the court overturning Roe v. Wade. Those who are overwrought by the prospect find themselves, constitutionally at least, on rather tenuous ground. For Roe could be decided only on the basis of a constitution that lives, where words and precedents cease to matter. Those who celebrate that decision and others like it have legitimized an arrangement whereby unelected judges are allowed, even encouraged, to exercise their will and impose their moral and political predilections on a people to whom they do not answer. But if that is all it takes to grant a right, then presumably no more is needed to take it away.

Whatever the fate of Roe, it seems an opportune occasion to recall the admonitory adage that “a government big enough to give you everything you want is a government big enough to take from you everything you have.” That those who clamor for the central holding of Roe to remain untouched would champion a living constitution, and with it the illimitability of the state, is an irony more likely to be lost than found.