We laugh at images of evil and make them sexy, and Carpenter's Halloween shows us the error of our ways.

The Nightmare of the Soul

Every good horror movie needs a skeptic. When the terrorized hero runs for help to the relevant authorities, someone is usually there to assure him—quite reasonably—that monsters don’t exist. The abominations that stalk through these films are dreadful not just because of what they can do, but because of what they are: they are the kind of thing that no one believes in anymore. And if no one believes in them, no one can stop them.

This fatal incredulity is a staple of the modern horror movie, going right back to its origins. Throughout the ’30s and ’40s, and into the ’50s, Universal Studios released its classic monster pictures. These were the movies that fixed the form in Americans’ minds: even if you’ve never seen them, they have helped define what you think of as a scary movie. Try imagining a stereotypical vampire without stage actor Bela Lugosi’s viscous Transylvanian baritone, immortalized onscreen in Dracula (1931): “I never drink…wine.”

This was the first of the true Universal classics. From its opening scene, the engine of the plot is doubt. “That’s all superstition,” says the real estate agent R.M. Renfield when warned about fearsome creatures that “feed on the blood of the living.” Viewers who had read Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel knew already that Renfield would soon become Count Dracula’s twisted lackey, gibbering in a lunatic asylum about his hunger for the blood of insects. In the film, it is Renfield’s disbelief that makes him such easy prey: he has no room in his imagination for vampires, and so he never sees them coming.

In the next year, Universal released The Mummy, familiar to Millennials by way of the 1999 remake starring Brendan Fraser. The original movie opens on archaeologist Joseph Whemple, who uncovers an ancient curse beside the body of a long-dead priest. Though his friend Dr. Muller pleads with him to leave well enough alone, Whemple grumbles, “I can’t permit your beliefs to interfere with my work.” Whemple’s assistant, the bluff young Ralph Norton, is still more callowly dismissive: “Surely a few thousand years in the earth would take the mumbo-jumbo off any old curse.”

When it proves that time has not cancelled the power of the old gods, Norton descends into a cackling insanity as the mummy walks among us. Like Renfield, Norton is driven mad by powers he refused to acknowledge even as possibilities. The modern mind cracks open under the assault of the supernatural, its brittle walls burst and broken by things it refused to conceive. The crucial error is to exclude all possibilities but rational ones—when in reality, “most anything can happen to a man in his own mind,” as Sir John Talbot (Claude Rains) says in The Wolf Man (1941).

Though Talbot does not believe in real werewolves, he has enough good sense to acknowledge that human philosophy can never encircle the heavens and the earth so entirely as to bring all things under the force of reason. “All astronomers are amateurs,” he tells his son (Lon Chaney), who will soon find himself twisted into the form of a wolf: “when it comes to the heavens, there’s only one professional.”

And there is the heart of the matter. For in point of fact we don’t believe in werewolves or vampires, or in ancient curses—at least not in quite the literal way that these movies depict them. The misgiving we express in horror movies isn’t that these sorts of monsters will materialize in the flesh. No, horror bears witness to a much subtler anxiety: the anxiety that man’s mind can never totally grasp, and so domesticate, the whole of creation. Again: “When it comes to the heavens, there’s only one professional.”

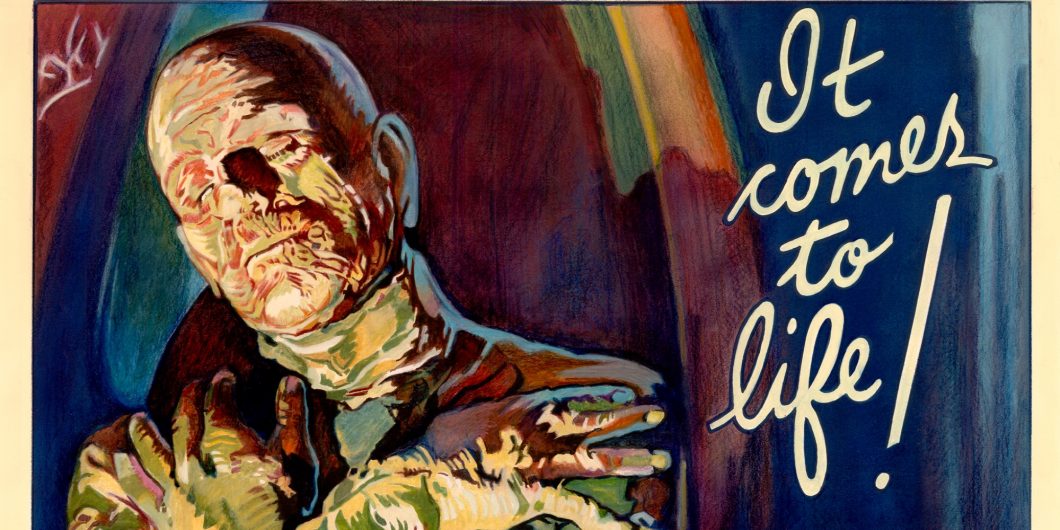

This is why the ancestor and originator of all modern nightmares is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), the book that helped create horror and science fiction alike as dominant popular genres. Universal’s 1931 rendition of Frankenstein, famously starring Boris Karloff, deviates wildly from Shelley’s original. But the movie retains Shelley’s diagnosis of her tragic hero, the Faustian doctor who hunts with “gladness akin to rapture” to “learn the hidden laws of nature,” as Shelley writes.

This almost worshipful curiosity, innocent or perhaps even virtuous in itself, mutates under the influence of grief into a ravenous quest for power and immortality. Dredging up and recombining chunks of human flesh in his laboratory, stripping the physical world of every enchantment and taboo, Dr. Frankenstein arrives at last at a kind of magic that actually works: the magic of material science, which gives him power over life itself. “First to destroy life, then recreate it,” says Frankenstein’s old professor, Dr. Waldman, in the movie: “there you have his mad dream.”

To bring all things into rational and mechanical order, subduing the physical world through the power of understanding—that is Frankenstein’s project, and ours. Once all things are describable in mathematical terms, then all things are controllable in predictable ways, even and especially our own bodies and minds. This is the appeal of regarding the human person as “a chemistry lab made of meat” or a computer program to be “hacked,” as it has become fashionable to do. That which has no spirit also has no idiosyncrasies, and so can be made to work just like a machine.

Here is a truly blood-curdling notion: there might be sorrows that clinical analysis cannot medicate or cut away.

But to strip the world of souls is to fill it with monsters. That is what Frankenstein discovers, and what we are beginning dimly to realize. By restricting his vision only to matter, by refusing to countenance the kinds of spiritual truths and natural pieties that would have held him back from robbing graves, Frankenstein blinds himself to every reality that cannot be brought under the power of his new science.

And there are such realities: the human form is not merely meat but the embodiment of a soul. The human mind is not simply a chemistry set but the seat of sorrow and joy, virtue and vice alike. Close your eyes to spiritual entities and they will not cease to exist: they will simply haunt the edge of your sight like specters. If you do not respect the human soul as a living thing, it will haunt you as a ghost.

Which explains why no horror movie can work without a skeptic, someone who refuses to believe in things that are not dreamt of in his philosophy. The skeptic is us: starting at a world that is more than matter, unable to see it for what it is. We are menaced by the supernatural precisely because we have refused to concede that it might exist.

So it is significant that our horror movies very often feature psychiatrists and psychotherapists. Take Halloween, the 1978 classic whose latest sequel, Halloween Ends, is in theaters this year. Mike Myers, the masked slasher who lurks in the shadows of that franchise, gives us chills because he is beyond the ministrations or even the understanding of contemporary psychoanalysis. “I spent eight years trying to reach him and then another seven trying to keep him locked up,” explains Myers’s psychiatrist, Dr. Sam Loomis. Eventually “I realized what was living behind that boy’s eyes was purely and simply evil.”

Here is a truly blood-curdling notion: there might be sorrows that clinical analysis cannot medicate or cut away, disorders that cannot be understood as neurochemical patterns and so brought under neurochemical control. That is the fear which drives Halloween, made flesh in the vacant eyes behind Mike Myers’s expressionless mask. He is a contorted reflection of everything we cannot acknowledge in ourselves—the parts of us that have no place on an MRI scan and cannot be tamed with the application of physical tools.

Or take Smile, another movie that has gripped audiences this Halloween. The psychiatrist Rose Cotter, who finds herself tormented by a grinning spirit of self-destruction, turns to her own therapist and demands a prescription for the drug Risperdal to cure her “fleeting moments of self-induced hallucinations.” But when her therapist turns out to be yet another manifestation of the same demonic force, Rose has nowhere left to turn. The demon is more than psychiatry can name or subdue—which means it is more than she can bear.

Neither science nor psychotherapy is without its uses. There are no werewolves, and no child of God is really irredeemable in the way that Mike Myers seems to be. But the point of our collective nightmares, the horror stories we tell ourselves this time of year, is not that some boogeyman might jump out from under our beds: it’s that some things exist which cannot be explained or drugged away with more and better physical science.

The mind itself cannot reduce everything to atoms, for the simple reason that the mind must be something more than atoms; material science itself relies on concepts and ideas that are more than material. The refusal to acknowledge this fact is what makes Frankenstein, and not his monster, the real cautionary tale. The mind of man can do great things, but it cannot bring the universe to heel. In that department, “there’s only one professional.”