Americans take to the road because it turns out that Bruce Springsteen was on to something: democratic souls are born to run.

The Perverted Salve of Power Outages and Close Quarters

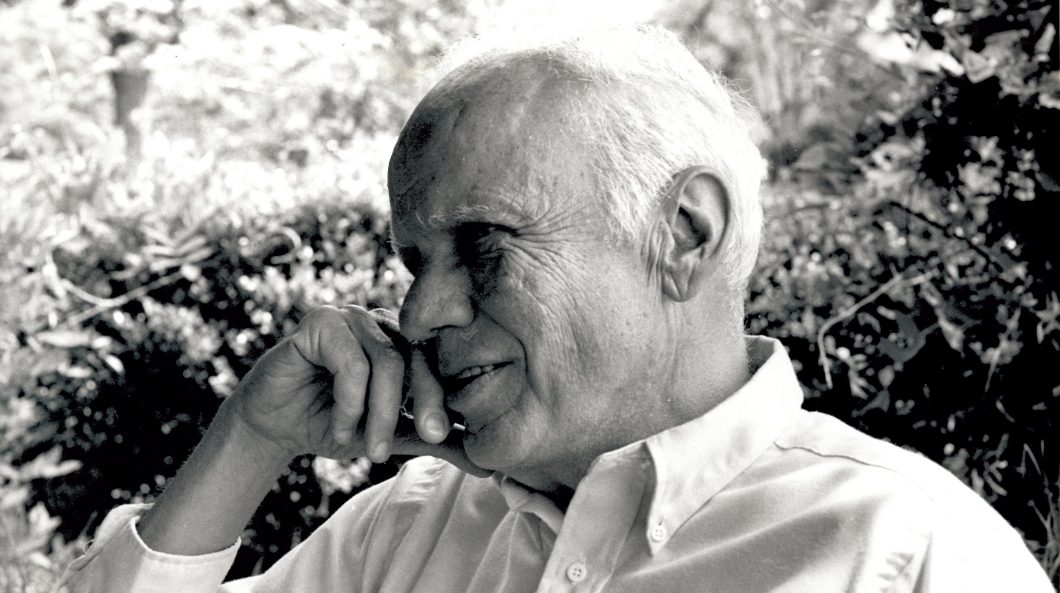

Walker Percy had an eccentric theory about disasters. Despite the modern consensus that calamities should be avoided at all costs, the National Book Award-winning novelist speculated that most people actually prefer them to safe, healthy, “good” environments. Moreover, the joie de vivre folks tend to experience in the middle of a crisis (think Louisiana “hurricane parties”) is, Percy posited, the most natural and healthy response for an inhabitant of modernity, with all its technological prowess and progress. Does the COVID-19 outbreak—a disaster if there ever was one—qualify as Percy’s “catastrophe as catalyst in the ontology of joy”? For Percy, the advantage of a disaster lies in its capacity to break through the humdrum, detached routines of modern living. The current pandemic, by contrast, requires us to double down on these very routines, thus revealing limits to Percy’s theory, but making it all the more important to understand.

Losing Houses and Gaining Homes in the Wrath of a Hurricane

An impending hurricane, Percy’s quintessential example of a happy “bad” environment, portends two things for a Louisiana kid: hip boots and sleeping pallets. Both are necessitated by frequent flooding and power outages, which, in the case of my extended family, rarely fail to gather us into the one house that manages best to escape damage—usually my childhood home. Located on a natural levee known as “The Bluff,” it boasts a grand 28 feet above sea level, more than 20 feet higher than any of my relatives’ homes. Still, 28 feet is not much when the Mississippi rages a mere five miles away. I’ll never forget the first time I heard a news reporter describe Louisiana’s peculiar condition of sinking. Dig seven feet deep in most parts of my home parish and you’ll strike water; a few more and you’ll hit the tops of full-grown oaks that have slowly been engulfed by swampland over the centuries. You know you’re on shaky ground when you’re walking on treetops.

Hurricane season is an annual reminder of our fragile state. Even if a hurricane takes a sudden turn or weakens, its potential wreaks havoc with our emotions and imaginations, conjuring visions of homes underwater or, like the embalmed trees, buried in silt. So why is it that some of my fondest memories are set in the midst of these terrifying tempests?

Part of a hurricane’s magic is that, to use Percy’s terms, it breaks the grip of everydayness, which consists in a mechanical approach to life as an endless to-do list of tasks and pleasantries. The mindlessness that ensues is “the enemy,” as Binx Bolling explains in The Moviegoer, because it makes a genuine search for meaning and purpose impossible. Now that modern science has satisfied nearly every physical need and want, offering in their place “a life without the old longings,” man’s soul is left in a peculiar predicament—longing for the old longings. Modern man’s state of malaise, in which he is alienated from the world and the people in it, can be fractured only by disaster’s visceral wake-up call: you are not a ghost in a machine watching your well-fed, well-medicated body go through the motions of 21st century life. You are a real human being in a real world with real aunts and uncles and cousins and grandparents whose real-but-now-warped parquet floors need to be ripped up. In interrupting our normal schedules, a disaster can wake us up to the possibility of a search. This freedom from the everydayness is temporary, of course, but, at the very least, the unpredictability of a disaster serves to remind us that the world is not an ephemeral abstraction but is, in fact, ours to, as Binx says, “stick [our]selves into.”

A tropical storm breaks through the malaise with power outages and, for many, forced togetherness, turning everyday routines upside down. When hurricane winds take the place of A/C, normalcy goes out the window. Thawing freezers might mean ice cream for dinner (or spiked mudslides for the parents?). Close quarters may force divorced grandparents to sleep under the same roof. Cousins stake out sleeping bag territory in the living room and gleefully evade bedtime enforcement while aunts and uncles settle into a Nertz or Bourré tournament while monitoring the weather.

In the absence of television or Internet connection, storytelling, by flashlight or candlelight, becomes a fundamental feature of these multi-day hurricane rendezvous. As kids, my cousins and I would marvel at trials from our parents’ and grandparents’ childhoods, like when our grandfather and his ten siblings’ photo landed on the front page of the local paper because they’d all contracted mumps at the same time, or when our grandmother’s house caught fire. My cousin’s favorite was the time a horse thief robbed our parents of their beloved pet Pal, but I preferred to hear about my great-grandfather and his friend Shoe hopping a cargo train to Michigan during the Great Depression. Lured by rumors of jobs, their hopes were dashed when the first thing they spotted in Benton Harbor were breadlines.

Our family lore was no less troubling than a hurricane’s foreboding squall lines, but it offered lessons for how to meet our fragile futures. The proper stance in the face of the perennial evils of mortal existence is not one of mastery or evasion, but one of clear-eyed awareness and daring embrace of the messy beauty and goodness of human life. Indeed, disaster is only half a remedy for the malaise. Storytelling about our catastrophic state can provide a second salve, as Percy often recognized.

For Percy, the advantage of a disaster lies in its capacity to break through the humdrum, detached routines of modern living.

Strangely, it “make[s] a man feel better to read a book about a man like himself feeling bad,” Percy muses in “The Delta Factor.” Even better to read such a book with others who also feel bad: “Why was it that when Franz Kafka would read aloud to his friends stories about the sadness and alienation of life in the twentieth century everyone would laugh until tears came?” Percy found inspiration for his own stories in the thought of Søren Kierkegaard, who wrote that the specific character of despair is to be unaware of one’s despair. A story about our vulnerable and alienated condition can at least make us aware of our malaise, but sharing such a story with others might deepen that awareness, allowing us to, “in the seeing, know that the other sees,” to quote Binx. We can then “listen to people, see how they stick themselves into the world, hand them along a ways in their dark journey and be handed along, for good and selfish reasons.” Rather than distract from the hurricane’s reminder of our mortality, our parties constitute the proper human response to it.

Home Alone in the Grip of a Pandemic

The current COVID-19 crisis has upended our modern lives in many ways, emptying physical classrooms, offices, churches, and restaurants, postponing weddings and conferences, canceling baptisms and funerals. What might formerly have been called agoraphobia now qualifies as good citizenship.

Yet perhaps our experience of this ongoing disaster falls short of the bizarre good “bad” environment Percy often pondered, in part because of the very scientific and technological advances that he thought made disaster salutary. Percy would have reservations about the two unique, albeit prudent, responses to the current pandemic—namely, the wholesale relocation of our lives to the Internet, and the social distancing that technology makes feasible.

Applications like Zoom and Instacart make it possible not only to work from home but to grocery shop from home, to attend class (and Mass) from home, and to go to the yoga studio from home. During this time of national shutdown, we find ourselves ever locked into the very routines that a hurricane’s tangible destruction makes impossible. Rather than break the grip of everydayness, this disaster risks exacerbating it. While 24-hour news coverage can bring images of the virulent reality into our homes, Percy might challenge that television’s flattening of this reality further distances us from it. TVs can be turned off, after all. For Percy, the speed and comfort of modern living aggravate the “invincible apathy” that makes everydayness the enemy. How much more numb might we become when images on a computer screen replace flesh-and-blood humans?

Stay-at-home measures are no doubt crucial for mitigating COVID-19’s spread, as is moving life online for sustaining the economy. Still, amid a 20-year sharp increase in “deaths of despair,” we would be wise to reconsider Percy’s observations about disasters, both the opportunities they afford and the limits imposed by our current crisis. Single-person dwellings now make up a third of American households, so many of us likely aren’t huddling with family and friends under one roof, sharing stories by candlelight. Nevertheless, we would do well, as much as possible, to let this disaster poke holes in the everydayness of twenty-first century living. The Italians’ now famous singing from quarantined balconies is a good example, as is New Yorkers’ clapping for healthcare workers from their stoops. A friend of a friend started a weekly Zoom story hour, during which he reads aloud from Love in the Ruins. Percy might turn over in his grave at the thought of such a 21st century perversion of Kafka’s practice. Then again, he might prefer it.