The Plot to Abolish Charter Schools

It’s time to “end the fight about charter schools.” So argues sociologist Eve Ewing, author of a book on “racism and school closing on Chicago’s South Side,” in a February 23 New York Times op-ed. Regrettably, she remarks, “discourse” over the merits of charter schools has become “ideological” rather than factual, blocking an opportunity to “reframe” the debate. Hence she urges the Biden administration to avoid “dogmatic” claims on both sides, instead “demanding high-quality, well-financed schools for all children.”

Wanting to represent her view of charters as open-minded, Ewing observes that different studies have come to findings as diverse as that despite improvements, charters “are less effective than their non-charter peers,” yet “are more effective for low-income students than for white and more affluent” ones, although (or because?) they tend to suspend disruptive students at higher rates. Additionally, charters “can improve standardized test scores and the likelihood of taking an Advanced Placement course,” are “more racially isolated” (that is, they enroll more minority students). Not only do charter schools “hire more teachers of color,” but attending them has been found to be particularly advantageous in high-poverty areas. And in what Ewing calls an “especially telling Economics of Education paper,” two Stanford scholars found that charter schools vary in quality (quelle surprise!) and that on the average “only19 percent (sic) outperform their non-charter peers in math and reading.”

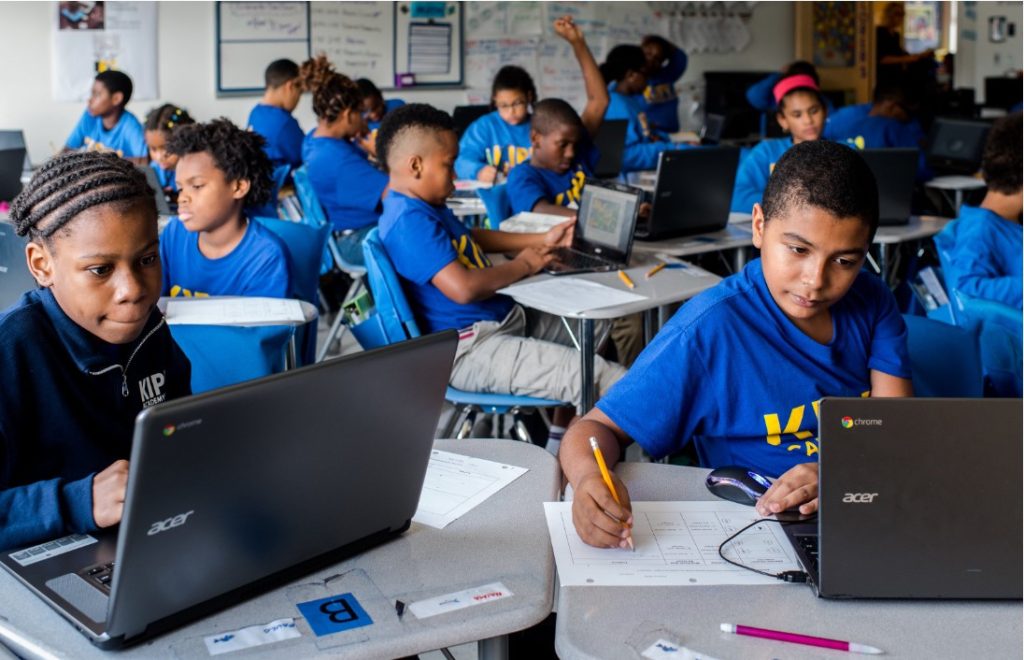

Generously, Ewing absolves parents of the over two million students of color currently enrolled in charters of “guilt for seeking the education they felt was best for their children in districts that have failed them.” But she reminds us that only about 6 percent of public school students attend charters.”

Ewing fails to mention the leading factor preventing that figure from being significantly higher around the country: the narrow limits imposed by state and local governments, at the behest of teachers’ unions and school administrators aimed at limiting competition—compelling charter schools to use admissions lotteries. Instead, she tries to divert attention by lamenting that the offspring of undocumented immigrants or the disabled are less likely to have “change advocates” acting on their behalf.

Ewing complains, without evidence, that such students lack “the smiling faces who attract big donors and awe-struck media coverage” that draw funding to charters—oblivious to the financial obstacles imposed by municipal governments that refuse to supply them even with vacant school buildings, requiring them to draw on private capital. In Massachusetts, for instance, rather than being provided with buildings by the city, charters must finance their acquisition through non-tax sources. And in New York City alone, as of 2019, over 50,000 children were on wait lists seeking admission to charter schools, while Mayor DeBlasio announced an end to their expansion and threatened further restrictions on existing ones.

But Ewing has a better idea: “an education policy agenda dedicated to ensuring [the largest] resources for all students, not just lottery winners?” Hence she exhorts Education Secretary Miguel Cardona launch “an all-hands-on-deck effort to guarantee every child an effective learning environment,” pursuing “the dream of great schools not through punishment (as in [George W. Bush’s] No Child Left Behind program,” or “competition (as with [Barack Obama’s] Race to the Top) but through the provision of essential [financial] resources?” Remarkably, Ewing regards state testing, designed to measure school and teachereffectiveness, as a form of “punishment”—perhaps because she describes herself as an advocate not only of racial justice but of “the rights of teachers,” who resent such impositions.

Yet even while claiming to distinguish herself from conventional “education advocates” who oppose charter schools outright, Ewing goes beyond traditional Democratic and union advocates of ever-increased spending on conventional public schools. Her program requires “abandon[ing]” policies that allow “education philanthropists” to donate funds to charters, as well as “ditching the philosophy that we attain excellence through private consumer choice—the idea that a great school is something that in-the-know parents ‘shop for’ …—in favor of a commitment to excellence for everyone.” Although Ewing never acknowledges this, far from favoring those “in the know,” charter schools go to considerable lengths to publicizetheir offerings among lower-income and immigrant communities.

Far from abandoning liberal dogmatism, Ewing not only wishes to prevent philanthropists from financing charter schools, but clearly would not allow the continued existence of publicly-financed vouchers (or privately financed ones?) that have enabled tens of thousands of kids from lower-income communities to attend private and parochial schools in cities like Milwaukee and D.C.

In 2019 D.C.’s deputy mayor for education opposed expanding school choice on the ground that there were already thousands of vacant seats in the capital’s regular schools—but evidently not enough parents wanted to take them given the system’s abysmal failures. If parents shouldn’t be allowed to “shop” for the best schools, perhaps we should prohibit them from moving from one neighborhood or town to another for that purpose?

In her penultimate paragraph Ewing finally arrives at her real message: charter advocates and skeptics must each heed the lesson of the pandemic: “educators don’t get paid enough”! She even warns that the pandemic will leave in its wake a growing “teacher shortage.”

Ewing’s column exhibits the way that conventionally liberal politicians and education scholars, like the post-1789 French reactionaries, have learned nothing, and forgotten nothing (of past failures). But unlike the reactionaries, their claims and prescriptions fly in the face of hard data. During the 2019-20 Presidential campaign, Socialist-Democratic Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders went so far as to claim that during the previous decade “states all over America [had] made savage cuts to education” and that “teachers are paid starvation wages and schools across underserved urban and rural parts of our country are crumbling.” During the same campaign Joe Biden asserted the existence of an estimated “$23 billion annual funding gap between white and non-white school districts today,” along with spending “gaps between high- and low-income districts.” To address those supposed gaps he called for a threefold increase in federal Title I spending, which totaled $15.9 billion in FY 2019.

But as a July 2019 Manhattan Institute report by Max Eden demonstrates, the claims of Ewing, Sanders, and Biden about a supposed shortage in public-school spending as an explanation of America’s education problems are misleading. As Eden observes:

Over the past half-century, America’s per-pupil spending on K–12 education has nearly tripled [in inflation-adjusted terms], and … now stands at an all-time high in most states. The U.S. spends more money per pupil on primary and secondary schools than any other major developed nation, and American teachers earn substantially more than their peers in the private sector. … [Although] spending varies widely between states, that variation shows little correlation with academic achievement…. Achievement gaps by race, class, and zip code still persist, but inadequate and inequitable school spending are not among the causes.

The causes of failure in America’s public education system are several and are widely known. They include high numbers of poor and minority kids coming from single-parent families that fail to provide the discipline needed to learn; a debasing popular “culture” that also discourages learning; increasing political and judicial limits on the capacity of schools or teachers to discipline recalcitrant pupils, interfering with the opportunity of their classmates to learn; high levels of mobility, especially among immigrants, between schools; and declining expectations of students from all socioeconomic levels, with textbooks in fields like history and literature assignments being dumbed down. But system failure is also sometimes due to rigid union regulations, which guarantee lifetime tenure to teachers before they’ve completed three years on a school staff (since the legal costs of dismissing even the least qualified or motivated ones once tenured are normally prohibitive).

It was largely to combat these latter sorts of decline that No Child Left Behind, as well as the superior state learning standards originally devised in Massachusetts starting in the 1990s following the bipartisan Education Reform Act of 1993 While Race to the Top ultimately accomplished little, at least it acknowledged the need to address our education problems by means beyond just spending more money.

Among the 65 charter schools in New York City in 2017-18 that shared buildings with traditional public schools, each having a predominantly black or Hispanic population and having at least one grade level in common, out of 172 grade levels tested in English, in 65 percent of those grades, “a majority of the charter school students scored at the ‘proficient’ level or above,” while only 14 percent of those grade levels tested in the regular schools scored at those levels—so “the disparity in achieving ‘proficiency’ was nearly five to one.’”

Although teachers—like all Americans—have faced a particularly stressful environment during the COVID pandemic, the reluctance of unionized teachers across the country to return to the classroom, despite extensive safety precautions and the fact that youngsters are less likely to transmit the virus, hardly justifies admiration, let alone a call to boost their compensation. For example, the Jewish day schools that my grandchildren attend have stayed open for in-person learning throughout the 2020-21 school year, with only periodic, limited shutdowns. Of course, they aren’t unionized.

But the most glaring omission in Ewing’s column is its disregard of the extensive scholarly literature—produced by distinguished social scientists without an ax to grind like Stanford’s Caroline Hoxby, Harvard’s Paul Peterson, and most recently Thomas Sowell. This literature demonstrates that charter schools on the whole greatly improve the educational and career prospects of poor, immigrant, and minority youth.

Sowell’s carefully designed study of charter schools aimed to measure the contribution that charter schools make to student performance. He compared results on the English and math tests that New York City administers annually to all students in both types of schools in grades 3-8. He focused his attention on NYC charter networks that had the largest number of schools sharing buildings with traditional schools whose grade levels coincided with theirs (hence with students having similar demographic characteristics, in buildings that were in comparable condition, in the same vicinity).

Although Sowell never claims that charter schools always produce superior results, his findings are striking—and far beyond the “19%” figure cited by Ewing’s authorities. Among the 65 charter schools in New York City in 2017-18 that shared buildings with traditional public schools, each having a predominantly black or Hispanic population and having at least one grade level in common, out of 172 grade levels tested in English, in 65 percent of those grades, “a majority of the charter school students scored at the ‘proficient’ level or above,” while only 14 percent of those grade levels tested in the regular schools scored at those levels—so “the disparity in achieving ‘proficiency’ was nearly five to one.’” When it came to mathematics, 68 percent of the charters’ grade levels had a majority of students scoring at the proficient level or above, while only ten percent of the regular schools’ grades attained that standard: a disparity of nearly seven to one.

Those who genuinely care about the welfare of America’s less-advantaged youth will take Sowell’s findings, along with those of Hoxby and Peterson, to heart. After his analyses, along with the findings about school spending summarized by Eden, it will be hard to take seriously claims that the solution to America’s education problem lies in throwing more money at it—let alone trying to further restrict if not abolish charters and vouchers.