The Rational Objectivity of a Man of Letters

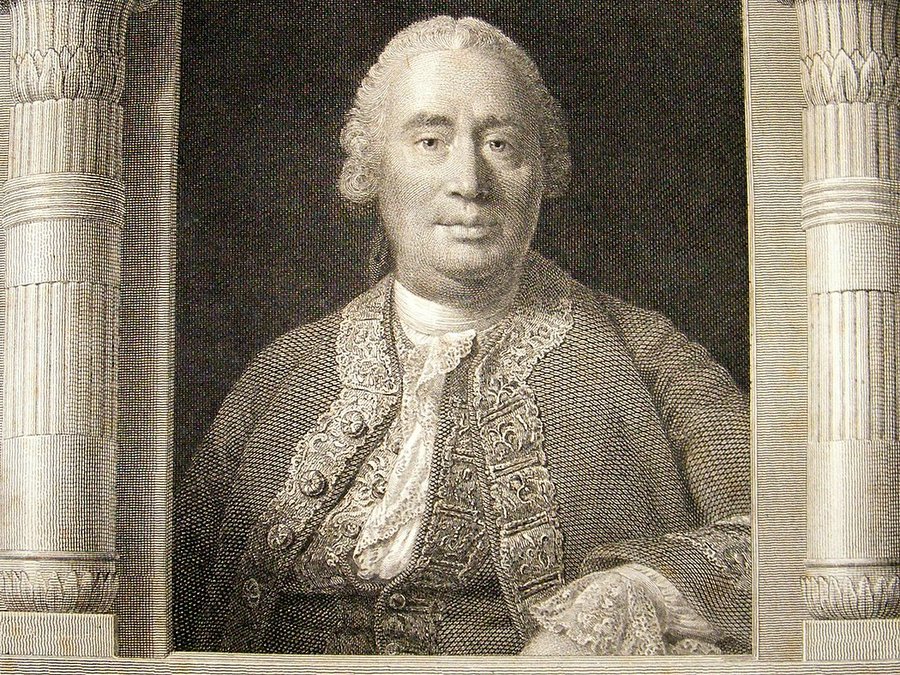

When David Hume died at the age of 65 in the year of the American Revolution, he was rich, famous, and often misunderstood.

Hume (1711-1776) is that rare bird amongst philosophers, a man who made a lot of money from his books. Though he was highly admired by a number of America’s Founding Fathers, his fame was in some respects problematic. His signature claim that reason is little able to justify most of our beliefs about the world upset many in Scotland, especially educators, and he was twice refused academic positions in his homeland.

Despite this, he could count as friends many of the leading lights of the French and Scottish Enlightenments. His ideas and manners earned him the fierce loyalty and friendship of Adam Smith, but other great contemporaries, like the philosopher and clergyman Thomas Reid of Aberdeen, criticized him for what Reid considered his destructive skepticism.

James A. Harris, an expert on 18th century British philosophy at the University of St. Andrews, has written the first intellectual biography of David Hume. This large work—500 pages plus another hundred of footnotes—is not only very welcome, but very fine, too. The book aims to explore Hume’s literary output in relation to his intellectual and political context and is full of engaging historical nuggets and interesting insights into the motives of one of Britain’s greatest thinkers.

Hume set himself two goals in life: fame and fortune. He wanted the fortune so that he could pursue the fame he believed would be forthcoming from a life spent as an independent man of letters. Hume’s father, a lawyer, set his son up with a thousand pounds’ capital. This gave Hume 50 pounds a year to live on—a modest income, but one that allowed him to move to France and reside near the famous Jesuit school, La Fleche, where the founder of modern philosophy, René Descartes, had been educated a century before. Here, at the astonishing age of only 26, Hume wrote his classic work, Treatise of Human Nature (1738), today one of the most influential of all philosophy books.

It is a large work, tersely written, and essential reading for those interested in scientific explanation, theory of knowledge, aesthetics, morals, philosophy of mind, and language.

By the time he died, Hume had grown his capital to give a yearly income in excess of a thousand pounds. He managed this by writing, and taking the odd, carefully chosen and remunerative job. He served on the general staff to some military expeditions, was appointed Keeper of the Advocates Library in Edinburgh, and did some diplomatic stints.

There is something curious about this, however. Harris argues that Hume always consciously saw himself not as a philosopher but as a worldly man of letters, in the mold of the Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713), who influenced him greatly. After writing the seminal Treatise of Human Nature, Hume largely transitioned to writing essays on matters of taste and commerce, before settling into the role of historian, penning his highly lucrative, multi-volume The History of England in the years 1754 through 1761.

Great philosophers tend to single-mindedly pursue abstract thought, and to write unrelentingly in developing that thought. Hume, by contrast, happily turned from philosopher to historian—the latter is how the British Library catalogues him—and, into the bargain, made his mark as a man of affairs.

In the latter part of his life, Hume took up various positions in the British government, including a diplomatic assignment to France in the mid-1760s. In Scotland, he was admired in some quarters and denounced in others; in France, he was adored. Known to all the leading lights of pre-revolutionary France, and invited everywhere, Hume chiefly relished his conversations with Anne Robert Jacques Turgot (1727-1781). With almost Burkean foresight, Hume found the philosophes somewhat “off” and most enjoyed talking commerce and public finance with Turgot, the man who was shortly to become France’s Minster of Finance, trying to hold back the deluge.

On leaving France, the bachelor Hume built himself a grand house in Edinburgh and there spent his last years throwing dinner parties as he indulged his hobby of cooking. In the last 14 years of his life, he barely wrote, and appears not to have missed it one jot. His gracious table earned him the sobriquet, le bon David, and it helped him remain at the center of Scottish intellectual life, as did spending several hours each day reading new Scottish works in the arts and sciences, as well as the Latin classics.

Another broad point made by Harris is that Hume saw himself as a European writer. Although he firmly believed that Scotland’s intellectual life in his time was second to none, and although he strongly supported some, if not all, of Britain’s military claims abroad—trying to hold on to the American colonies was militarily a lost cause, he believed—he nonetheless did not write as a Scotsman or as a Briton. As Harris points out, if you were to read Hume’s essays without knowing either who wrote them or if they were translations, you would have few indicators as to whether they were written by a Frenchman, a German, or a Briton.

This stems from a peculiar quality of his writing, its cool detachment. In many ways, it was Hume’s detachment that made him controversial and misunderstood. Another factor is that, while Hume is likely to have written thousands of letters over the course of his life, most were destroyed. In his will, he charged his friend, Adam Smith, with the task of getting rid of his papers, a fairly common practice in the 18th century. Smith did a very thorough job. Only two original manuscripts exist of all of Hume’s varied writings, and of the surviving letters, only a handful cast any light on the gestation of his ideas.

One letter, however, reveals much. Hume wrote as a young man to a doctor in London detailing a mental breakdown. The antidote to his mental fragility was detachment. Hume’s unmerciful analytical coldness was often read as a passionately iconoclastic subversion of other people’s deeply held positions. But nothing was further from the truth: Hume was not passionately for or against anything. He dared not be, understandably anxious not to trigger a recurrence of his mental instability. He used his reason to clinically assess the rational support for various beliefs. This rational criticism was skeptical; it was not a dogmatic rejection of others’ cherished beliefs. A call for more rigorous justification is not the same as radical subversion, so Hume believed.

Being a mannered and amiable man recommended Hume to many, and while his precise reasoning, and the sangfroid with which that reasoning operated, battered the cherished beliefs of the age, his aloof ways proved a boon politically. The Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 put all Scots in Britain in a difficult position, not least any Scot wanting to write about British history. The United Kingdom celebrates the Queen’s 90th birthday this year but in Hume’s time, to consult the historical record to assess the legitimacy of the Protestant Succession and the House of Hanover was to enter a minefield.

On utilitarian grounds, Hume was a convinced Hanoverian: he subscribed to the Whig position that the commercial growth of towns and cities would prove a vehicle for British power and also prove to be the agent of a reformation of manners. (My previous Law and Liberty contribution related to this aspect of Hume is here.) His reputation for philosophical atheism and rational objectivity, however, left him free to find in the historical record evidence of the Stuart monarchs’ political actions being in conformity with practices dating at least back to the Tudors, especially Elizabeth I. The Toryism of the Stuarts was a longstanding, validated part of British tradition. So well did Hume pull off this balancing act that he was given various posts in Hanoverian administrations.

Hume: An Intellectual Biography is both richly researched and highly readable. Through the life and work of this remarkable Scotsman, Harris offers an expansive treatment of the ideas and political currents of the 18th century, which laid the contours—and the fault lines—of our own time.