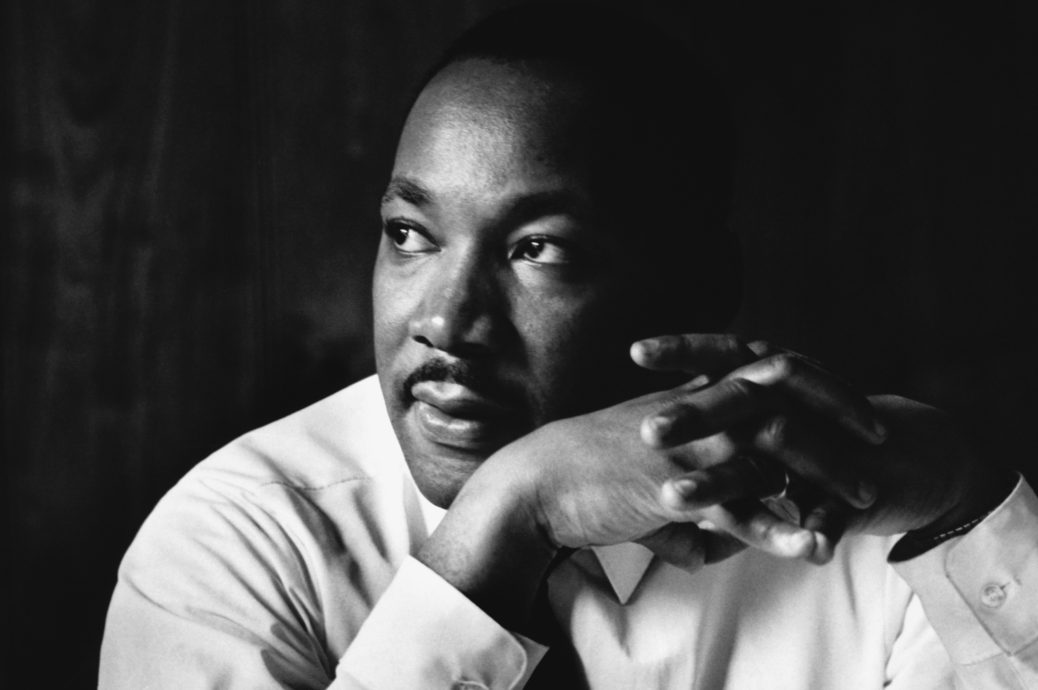

The Vanished World of Martin Luther King

With today’s honoring of Martin Luther King, Jr. come new skirmishes in the turf war over his legacy.

Tradition holds that radicals on the Left own it. Because the civil rights leader was most radical near the end of his life, that King allegedly proved to be the truest. The King of the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign is deemed to be better than the younger, greener, and more obviously Christian King of the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott. He engaged in acts of civil disobedience, including boycotts, demonstrations, sit-ins. He went to jail to demonstrate the violence at the heart of the white supremacist state. He also vocally opposed the Vietnam War. King sought to relieve the racially and economically dispossessed by way of government programs that would redistribute wealth from the richest Americans.Recently, conservatives have sought to claim King for their own. They concede that he favored political and economic programs far to the Left of what a conservative would want. In addition, they concede that conservatives of King’s time failed to appreciate his prophetic witness against segregation. Conservatives argue, however, that his civil rights activism rested on a solidly conservative foundation.

First, King understood himself to be primarily a preacher of the Christian gospel. The contemporary Left has abandoned any kind of religious faith—indeed, has laid bare its hostility toward it.

Second, King remained committed to preserving a civic faith in the American Founding, especially as interpreted by Abraham Lincoln. The contemporary Left has broken with the Founding, regarding it as hopelessly racist and capitalistic.

Third, King insisted on a “colorblind” standard for American race relations, calling on his fellow Americans to create a nation where his children “will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Who has the true claim to King’s legacy, the Left or the Right? The answer is both, but in fact the claims of both are weak. For example, Amy Gutmann has sought to divorce King from his Hebraic-Christian foundation, arguing rather incredibly that his arguments “are not uniquely tied” to his faith but retain importance because he argued for “reciprocity . . . across different ethical identities.” Gutmann’s position is untenable. King rested his entire economic and political activism in what he viewed to be the Christian demand for justice.

Equally untenable is the conservative appeal to a supposed colorblindness in King. King always stressed the importance of cultivating a sense of black pride in the numerous African American contributions to American greatness despite the indignities and even atrocities white supremacists waged and moderates generally disregarded. He said: “The tendency to ignore the Negro’s contribution to American life and to strip him of his personhood is as old as the earliest history books,” to which the black men and women must respond “I am somebody. I am a person. I am a man with dignity and honor. I have a rich and noble history,” and finally, “I’m black and I’m beautiful.”

The Left correctly claims King’s legacy of activism and his social democratic ideas of political economy. The Right is correct to claim King’s religious foundation and his celebration of the American political tradition. Even so, the critiques that the two sides level against the other are also true. By bracketing out King’s political and economic positions, the Right gives away much of King’s legacy to the Left. By ignoring King’s deep Christian foundation for his social democratic politics, the Left purges the faith that drew in King’s multiracial, ecumenical alliance of support.

Consequently, ideological defenders write and rewrite the same articles with no hope of resolution. Those on the Right claim King’s religiously grounded, patriotic colorblindness and find challengers on the Left insisting he was a radical socialist breathing fire on white supremacy. In truth, he was both.

What is at the heart of these competing claims? I would say that it is the demise of the America in which King lived, and that two elements of that bygone America are key. The first is what King called the “Hebraic-Christian” heritage, which in his day was expressed as an alliance among liberal-minded Protestants, Catholics, and Jews (recently explored in the works of Matthew S. Hedstrom and Kevin M. Schultz). This alliance has declined. The second is a faith in the administrative state to provide economic benefits for all, which has also declined.

When in the winter of 1955, a coalition of local black Christian congregations gathered in Montgomery Alabama’s Holt Street Baptist Church and thrust the Reverend King onto the world stage, King preached not merely to those assembled but to the mainline Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Jewish congregations across the nation. The three major American faiths had formed something of a détente. Mainline Protestants had accepted the end of the 19th century Protestant hegemony forged during the Second Great Awakening and preserved during the post-Civil War political dominance of the Republican Party. The Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the Second World War ended Protestant hegemony politically, and the postwar surge in mobility and suburbanization ended it culturally. Increasingly, Protestants, Catholics, and Jews were neighbors, and found much in common. Furthermore, the existential threat of the Soviet Union during the Cold War demanded that Americans put aside their differences to confront a common foe.

From the 1930s until the 1950s, mainline Protestants retained their status as first among equals. They had the most elite congregations, the most access to institutions, and the most money. The 1950s, however, ushered in an age of economic upward mobility that granted the very numerous Roman Catholics in the United States considerably more influence. At the time of King’s famous sermon on Holt Street, a Roman Catholic bishop, Fulton J. Sheen, was one of the most popular figures in the United States. American Jews were viewed sympathetically by their countrymen because of the Shoah, and the importance of the new state of Israel as geostrategic partner and, for some Protestants, an eschatological marker of the Second Coming.

Catholics and Jews even wrote competing books on inner peace—Rabbi Joshua L. Liebman’s Peace of Mind (1946) and Sheen’s response, Peace of Soul (1949)–books, incidentally, that King criticized—with Mainline Protestants making up a considerable part of the readership for both. The rise in Catholic and Jewish prominence led to the formation the “Hebraic-Christian” or now more commonly called the “Judeo-Christian tradition.” All three faiths stressed points of agreement, and did so as equals.

Even as Jews, Catholics, and other descendants of the second-wave immigrants to America from Europe achieved upward mobility, most mid-20th century institutions continued to bar African American entry. King appealed to the Judeo-Christian tradition that the black church shared to demand that white Americans remove these barriers.

His most famous speech is the one he gave at the March on Washington, but often forgotten is the full title of that 1963 event: “The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.” King insisted on political liberty and economic prosperity. Other speakers and prominent guests at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial were black union leaders demanding entry into a unionized labor force that was garnering increasingly healthy wages in a booming postwar economy.

It is no accident, either, that King’s first leadership position was managing a form of economic civil disobedience—a boycott. That same economic civil disobedience was part of his last leadership position. On that fateful day in 1968, he was in Memphis to lead a strike of sanitation workers—a strike that, after King’s murder, resulted in recognition of the union.

This was a demand for prosperity, moreover, within the framework of the new administrative state. King wanted government recognition of black labor unions and the integration of the American workforce to harness the government’s power to regulate industrial and commercial activity for the benefit of minorities. His premature death meant that he did not live to see the rapid decline of this model of economic mobility.

He died not just with faith in the gospel but in the federal government’s capacity to improve the economic lives of black Americans just as it improved their political lives with enforcement of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. For King, poverty-relief programs provided the bridge between economic segregation and access to good jobs and good wages. By the time African Americans made inroads, however, the mid-century economic expansion was almost over, and it was too late for black workers to benefit. Of course, King had no way of knowing events would unfold this way.

The foundation for King’s economic appeal was the same as his political appeal, which overlapped with his religious appeal to the Hebraic-Christian tradition. He argued the following: Protestants, Catholics, and Jews all agree that the sacrificial love of agape provides the model for our relationships with God and with each other. Agape demands that individuals place neighbors and even the whole community ahead of personal interests—a sacrifice that, performed individually by all, brings individuals together in greater social trust and respect. These sacrifices produce greater benefits to the individual than strictly following self-interest, since the redemptive power of love provides valuable spiritual redemption over mere material satisfaction.

King grounded this appeal in an ecumenical approach to Scripture and religious tradition. Perhaps his most famous piece of writing, “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” was the most emblematic of this approach. The letter is addressed to the local white Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish clergy who had asked King not to march in Birmingham. It speaks nominally to them but, in truth, to co-congregants across the nation. It invokes figures that would satisfy each denomination. King spoke of the gospel, St. Paul, and St. Augustine, and Paul Bunyan for Protestants. For Catholics, he added St. Thomas. King spoke to Jews through references to Martin Buber and the Prophets.

Tying these three traditions together are several imperfect, yet critical, examples of American statesmanship with respect to racial equality. King does not argue that America is a Christian nation or that it serves some unique role in the salvation of humankind. Rather, he sees in the American Founding the same agape consensus of individual sacrifice for the improvement of the whole.

He specifically focuses on Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln as relevant to the American dream in which all citizens should equally participate, and he sympathetically critiques Jefferson and Lincoln for their imperfections on issues of racial equality. King appealed to these statesmen as having, however reluctantly, done the right thing. His audience was white Americans, but especially the liberal Republicans and non-Southern Democrats of the country’s political leadership. The weight of civil rights reform rested on them to finish what Jefferson and Lincoln had imperfectly started, says King, since African Americans could not affect the political process due to their disenfranchisement.

The Hebraic-Christian tradition, as a political consensus, completely fell apart thereafter—another development King did not live to see. The New Left, already visible during his life, came to violently reject the bourgeois, anticommunist Democratic Party, with the Republican Party moving to pick up the mostly white voters whom the Democratic Party was perceived to be abandoning. Many of these white voters were evangelical Protestants who had, either tacitly or overtly, opposed efforts to implement civil rights reform, though some would moderate or even repudiate their old positions. While these repudiations were often sincere, some were also convenient.

In the 1970s, the white evangelicals of the American South suddenly made a reentry into politics (from which they had withdrawn after the fiasco of Prohibition) and thus were engaged in the kinds of efforts that they had condemned when African American preachers engaged in them in the previous decade. At the same time, the mainline Protestant churches, already in decline, sunk deeper into that decline. And the African American civil rights leadership fragmented.

In fact a harbinger of that fragmentation came in King’s time. Notwithstanding his demand for greater political equality, he had organized the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with the top-down leadership style of a church. An early opponent of the hierarchical model was Ella Baker, once an SCLC leader but disillusioned during her three years there (1957 to 1960). She sought a more egalitarian and even collective leadership, which has survived that period and is now the dominant form of political organizing.

In short, the political and economic message of King today has no home in either political party because the world in which King prophesied racial equality has vanished.

Rather than affirming the Left or the Right, King’s legacy challenges both. The Left must come to terms with the failure of the very administrative state and poverty-relief programs that King himself hoped would uplift African Americans out of the conditions imposed by centuries of slavery and segregation. In addition, King’s vocal, unmistakably Christian language puts in sharp relief how today’s conditioning of a genuine democratic consensus on a secular discourse does not enhance the possibility of debate—it dramatically shrinks it. It even excludes those like Obama administration veteran Michael Wear, who recently made news discussing the tremendous ignorance of Christian ideas among his fellow Obama staffers.

By the same token, conservatives must recognize that African Americans cannot accept the notion of a colorblind society, since such a view denies the historical place of African Americans in the history of the United States. Conservatives celebrate the Declaration of Independence as the moral foundation for republican government, but, as King reminded his audience, the Declaration was a revolutionary document in its defense of individual rights. Slaveholders and segregationists were the ones who tried to stop that revolution, and they did so specifically to deprive African Americans of the rights the Revolution was supposed to restore.

Martin Luther King carved out a place in American tradition for African Americans to call their own, yet he understood this tradition as part of a larger whole, one which would refine and repair the injustices of the past. As he once preached, on July 4, 1965, with the voices of his Ebenezer Baptist Church congregation calling back to him:

And I tell you this morning, my friends, the reason we got to solve this problem here in America: Because God somehow called America to do a special job for mankind and the world. (Yes, sir, Make it plain) Never before in the history of the world have so many racial groups and so many national backgrounds assembled together in one nation. And somehow if we can’t solve the problem in America the world can’t solve the problem, because America is the world in miniature and the world is America writ large. And God set us out with all of the opportunities. (Make it plain) He set us between two great oceans; (Yes, sir) made it possible for us to live with some of the great natural resources of the world. And there he gave us through the minds of our forefathers a great creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men (Yes, sir) are created equal.”