The 1938 film showed us what is admirable in young women and what inspires young men.

The Voight-Kampff Test

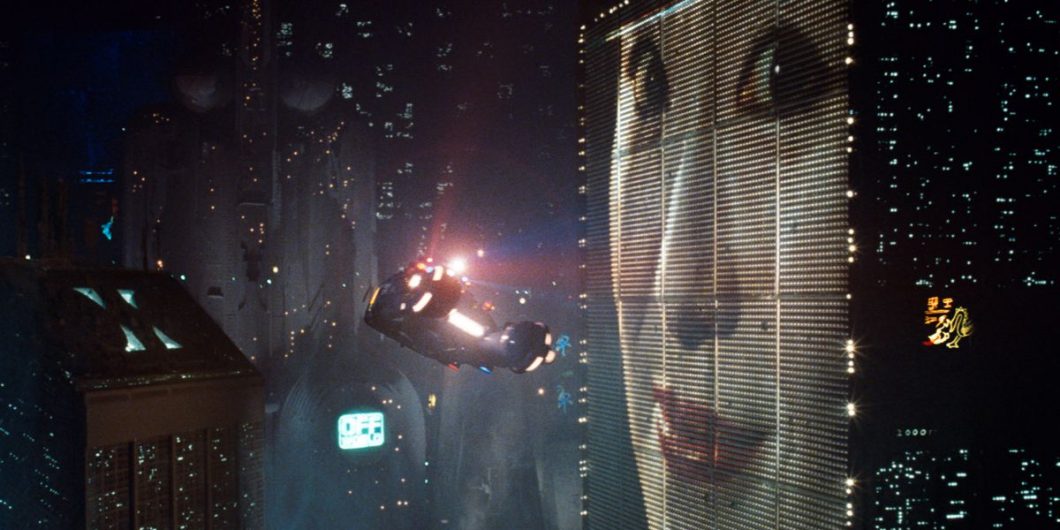

The year 2022 is the 40th anniversary of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, perhaps the most influential vision of the future cinema has presented in this generation. Moreover, we may say we have been living in the Blade Runner future for a while now, since the movie is set in 2019. It’s worth asking ourselves, given Blade Runner’s profound influence over movies, TV, and computer games, what is it that we learn about ourselves from such a shocking, unwelcome story of tyranny overwhelming everything we treasure about America?

As with all science fiction set in the near future, Blade Runner is an attempt to make us look at ourselves as though we were strangers to ourselves, allowing for the possibility that serious changes can come suddenly and overcome our beliefs or preferences. Could we end up like Deckard, Harrison Ford’s character, a bounty hunter, or “blade runner?” Shockingly for a Hollywood protagonist, his job is to enact the Fugitive Slave Act, as my friend Pete Spiliakos puts it. Granted, he’s hunting down apparently human robots called “replicants” rather than slaves whose humanity was insufficiently apparent. But he is aware it’s dirty work, he quit his job with the police for that reason. Indeed, he is compelled to do it by his former police captain’s threats and the evidence that the replicants are murdering people. Perhaps Deckard’s no freer than the replicants he chases. The plot forces him to face the futile cruelty of his activity, to bring him to existential questions about his own humanity and what it demands of him.

Yet Deckard at first recalls a Philip Marlowe character, a private detective in a corrupt Los Angeles, the future resembling the past. America could do worse than rely on the honor of individual citizens who will not make a travesty of justice or ignore the suffering of victims. But Blade Runner doesn’t fit Raymond Chandler’s vision, because technology has displaced glamour and money. There may be no romance left, no beautiful lies to reveal, indeed, one almost wants to say, there’s no beauty left at all in this gloomy, storm-drenched future. Certainly, that’s Deckard’s view of life at the beginning of his adventure.

Questioning Humanity

We need not embrace this kind of despair, but only need understand its appeal. The social landscape of Blade Runner seems plausible enough. The film presents American cities overrun by crime and poverty while technological corporations become immensely wealthy. Indeed, these companies are seemingly the last competent organizations, as politics disappears and administration is both overextended and inept—cluttered, corrupt, confused. A suitably dramatic expression of something we see around us quite often; indeed, perhaps exaggeration is necessary, since we have an excusable, but unfortunate tendency to ignore the misery of American cities.

Though unhappy, these cities are identified with the future, both in the sense that business and money concentrate there and that the young especially want to live there. Our way of life offers at present no relief from an unlivable situation, except suburbia, which however is not a vision of the future. Therefore, it is obvious, and it bears stating, that our visions of the future are now almost always colored by rather dark passions. Optimism, where it endures, is typically inane, vague, unable to say what good things we might achieve or how. It has little in common with a younger America, where everything from science to poetry seemed to be giving people energy and specific purposes to pursue.

Thus far, Blade Runner would seem to be a prophetic warning of realities we experience today, but it may also be called a memory of the similar ugliness of the ’70s, a threat of social collapse. That is also when ugliness came to be considered a virtue of our cinema and, indeed, our storytelling has since cultivated a taste for ugly truths, or at least what are believed to be ugly truths. Yet we may heed these warnings, we may be brought to face our weaknesses or even vices, without entertaining despair. Blade Runner justifies its dark mood not by sociology, but by a deeper, psychological inquiry into the troubles of the American heart. Going beyond practical concerns, the work of art is compelled, and in turn compels us, to look at the things we usually ignore, for the sake of decency.

To hunt replicants, Deckard and the rest of the strange police force he’s part of, must first identify them as such. Blade Runner thus forces us to ask how we know we are human, suggesting that uncertainty about that question leads its character to a strange, gratuitous cruelty. In the movie, supposed experts, themselves untested, subject others to tests of their humanity, all the better to prevent the raising of the question, what is humanity? The authorities claim that replicants are only pretending to be human—but what except a human being would pretend to be human? In the movie, this is mankind’s last available form of piety, trying to defend an idea of humanity from the consequences of technological power, the robots.

Digital America

The questions concerning humanity that advance the plot of Blade Runner are neither the vanities of storytellers, intended to perplex us, nor fantasies supposed to afford us some kind of escapism. Just consider the parallels to our social media. We are ourselves in the process of installing all sorts of technological-ideological partnerships and systems to test and refute claims to humanity. All the recent talk about “disinformation” and “misinformation” is intended to institutionalize the censorship of political opinions, to delegitimize political dissent in an authoritative, elite way, and eventually to deny Americans their rights. This is all worrisome, but not yet beyond our ability to find political redress. The further problem is the basis on which these moral-intellectuals claims are formulated, putting woke experts and technological tools like algorithms in charge of deciding not just who’s a real American (as opposed to a Russian bot, for example), but who’s even human.

The screens through which most of us mostly meet other people obscure our humanity as well as theirs, the very thing we have in common, on which basis we could begin to form communities. Our aspiring techno-tyrants are themselves victims of this process, yet they think they will master it by removing our humanity. The language used online increasingly reveals this problem, going beyond the elite jargon concerning information and the government-corporation conspiracies to censor political, scientific, and other opinions.

Blade Runner issues from a humanistic intention, which requires the use of replicants to give us an image of ourselves, with our fears and hopes, our aspiration and despair.

The vaguely rightwing online crowd routinely mocks people as NPCs, that is, non-player characters, mere algorithms. This word is taken from computer games, which increasingly have become a source of the images used to describe our world. Moreover, the common reference to bots everywhere from political polemics to legal wrangling between Twitter and Elon Musk suggests a Kafkaesque fear that nobody around is really human, that we’re talking to machines and, possibly, transforming into machines. These are to some extent descriptions of online behavior. They even have a power to persuade or compel, which is called “gamification,” an attempt to persuade people to live online as though in a game, chasing fantasms as rewards, allowing algorithms to block their options. To that extent, they testify to our almost willing dehumanization, further giving credence to the psychological, not to say poetic and spiritual warnings in Blade Runner. We are not very far from the world that movie envisions; we are certainly close enough to recognize these disturbing similarities.

Do we understand ourselves and our possibilities adequately? This question arises from Blade Runner and replaces the poetic depiction of an America reduced to despotism. We follow Deckard on his quest and, along with him, begin to discover the humanity of the replicants, and eventually their nobility, which cannot but inspire our own. We are somehow led to admit that we need drama, conflict, polemics of the right kind to reveal the humanity we stand to lose or gain, but which we cannot take for granted. It would be a long political work to understand how technology and institutions should be interpreted in that light, which is beyond the work of the critic as it is beyond that of the storyteller.

Poetic Defenses of America

It must suffice here to reveal that Blade Runner issues from a humanistic intention, which requires the use of replicants to give us an image of ourselves, with our fears and hopes, our aspiration and despair. The movie uses the image most attractive to audiences nowadays, by reason of novelty and promise of power, technology. After all, of the many billionaires and vastly more numerous millionaires in America, the one Americans find most fascinating and scandalous is Elon Musk, who makes rockets and robots and who wants to recreate social media and neural networks. Perhaps Blade Runner understands him as well as it does our society.

Deckard learns to deal with the temptation to despair by quitting working for a despotic institution, falling in love, and learning to respect the nobility of an adversary, or recognizing the tragedy of the human condition. One sees similar choices in our times, showing not just that much of the cinematic diagnostic is correct, but that some of the prescriptions are, too. Properly understood, to put the diagnosis and prescription together is a matter of self-respect—respecting ourselves as a society by taking social phenomena seriously and respecting ourselves as human beings, bound by choice. It is perhaps the special power of poetry to move us to action by what initially seem to be dark or at least gloomy visions. Since this is the national mood now, we had better make the most of it rather than wish it away.