The Youngest Citizens

As a nation of immigrants, the United States has long debated the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. Until recently, a consensus existed that the two belonged together. A century and half ago, the melting-pot ideal helped waves of newcomers to assimilate and to embrace the coveted privilege of becoming citizens. It was the glue that held the whole together. Increasingly, this paradigm is being replaced with the emergence of self-anointed “global citizens” (by definition an oxymoron) and the explosive growth of legal “residents,” neither of which require or promote civic duties. Many school districts are adopting “action civics” which encourages activism and protest, but not obligations. Without foundational training in civic duties, why would young people want to join the military, show up to vote, serve on a public board, or care if their city spirals downward into an abyss of crime and poverty?

Perhaps we can learn something valuable by examining how the nation once taught children civic requirements to create a set of shared values that bound together a country every bit as diverse as ours is today.

The importance of civic duty was woven into many children’s books during the early 20th century. The focus was more on responsibilities than rights that authors presented as a sacred inheritance and trust to be nurtured, protected, and passed down intact to the next generation. In contrast to the dry schoolbooks of today (with their distracting pictures, diagrams, and charts on nearly every page), which primarily just describe the structure of American government, these earlier texts sought to situate America in the grand sweep of human history and explain how its institutions followed a preceding arc toward liberty and civic engagement and brought them to their fruition.

Young Citizens

A good example of this was the work of Paul S. Reinsch, a professor of government at the University of Wisconsin. Reinsch was a well-known and respected political scientist and diplomat, representing the United States at international gatherings and eventually as Minister to China. Yet before Reinsch left the academy for the world stage he published The Young Citizen’s Reader (1909). Note the word citizen in the title (rather than person or student), which itself is laden with the burden of responsibility. From the Latin civitas, meaning a city, the term citizen first appeared around 1300 in the French form of citisein and by the late 1400s had come to denote the member of a state or a nation. By the 1790s, in the midst of the French Revolution, the more democratic and republican citoyen had replaced the aristocratic Monsieur. A citizen not only enjoyed membership in a state and its protection, but owed reciprocal obligations to it. They ranged from the abstract (loyalty) to the compulsory (military service).

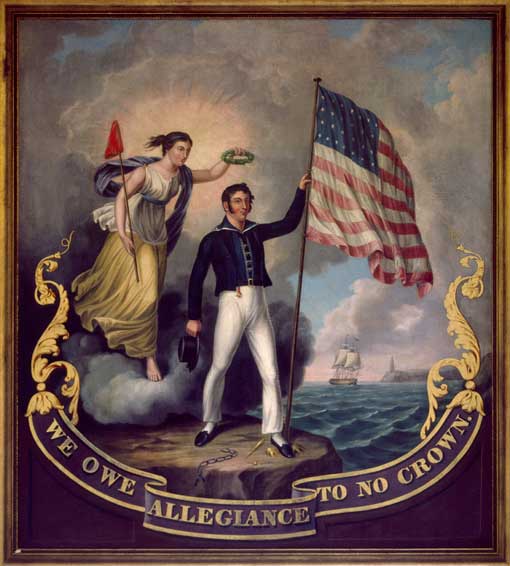

Membership did not come free. Americans embraced the term around the time of the Revolution as it perfectly embodied the creed of the experiment in republican government they had launched. It would have been unthinkable to continue the British term subject since it derived from the Latin “to throw under” and by the 14th century meant “person under control or dominion of another.” While an Englishmen certainly enjoyed rights and privileges, his status as a subject denoted a sense of subservience and deference unimaginable and abhorrent to most Americans nurtured in an increasingly egalitarian nation. This belief was well exemplified in artist John Woodside’s painting, during the War of 1812. In it, Lady Liberty, descending from the clouds, places the olive wreath on the head of ramrod straight, American sailor proudly holding the Stars and Stripes. Underneath the caption reads: “We Owe Allegiance to No Crown.”

Citizenship was gradually expanded to include previously excluded groups. African Americans secured it with the enactment of the 14th Amendment in 1868. Native Americans, the original inhabitants, were denied citizenship until enactment of the Dawes Severalty Act (1887) which made them eligible, but only if they “adopted the habits of civilized life.” In 1924, the federal government finally granted it unconditionally to all Native Americans. Unless we are an immigrant or a newly minted citizen, most of us take citizenship for granted today, not realizing how jealously guarded and stingily bestowed it was for most of the nation’s history.

Reinsch made clear how different America was, tracing for the young reader the history of government from chieftains to kings, specifically noting “our idea of government is different.” He indirectly references the Lockean contract and our foundational document, the Declaration of Independence. “We cannot,” he writes, “live happily unless we obey reasonable laws which protect the lives and property of ourselves as well as others.”

Fortunately, we possess older, wiser and salient models for children, such as Roosevelt’s, and can borrow from the best of them. Resilience, courage, and self-reliance remain worthy goals for young men—and young women.

In addition, he cites the centrality of civic organizations such as schools, churches, universities, business associations, and clubs. These constitute the institutions that play a mediating role between Americans and their government. Reinsch clearly wants the young reader to grasp that he or she is part of a larger civil society, one that they are obligated to support and that will, in turn, support them. He also reminds them of the importance of virtue, the classical ideal from the Roman republic that the Founders so frequently cited as indispensable for the survival of liberty. Reinsch wanted his readers to grasp the fragility of our institutions and their dependence on the character of those who controlled them:

They [elected leaders] ought, therefore, to consider the welfare and interest of all members of the state. The government is not something apart from our life, something outside of us, set over us; it is simply ourselves, the people, acting for our common benefit. The men who we intrust [sic] with power do not have any special privilege, nor should they look upon their office as a source of advantage to themselves. . . We need faithful, unselfish public servants who really think of and work for what is best for the community, that is, for all of us. . .

Note the prescriptive terms writers did not hesitate to use in children’s books in contrast to the more non-judgmental models today. Elected leaders ought to think of what is best for the community. Americans entrust them with power and expect them to cherish and safeguard it. They must remain unselfish and honest. Most importantly, Reinsch references the importance of character, so important to the Founders. Since any citizen, in theory, could hold public office he had to remain pure and beyond reproach. In essence, leadership emanated from citizenship. Any flaws in the latter would degrade and corrupt the former.

Even the chapter questions reflect how writers encouraged children to ponder their duties and what it meant to be a citizen. For example, Reinsch asked: “Are you a citizen? Of what? Tell the difference between a voter and a citizen.” He wanted to make clear to young readers that voting was a mechanical action, the exercise of a right (albeit a sacred one), merely part of a larger whole. Simply selecting an officeholder did not affirm the voter was a true citizen, but rather that they had checked off an important box, by no means the only box, on the list to being one. He also asks: “What is patriotism? How can boys and girls show their patriotism” It was not enough for children simply to understand national devotion, but also how to display it.

TR on Citizenship

One year after Reinsch published The Young Citizen’s Reader, civic boosters created the Boy Scouts of America, based on the English model forged by war hero Robert Baden-Powell in 1908. Not surprisingly, ex-president Theodore Roosevelt heartily approved and took a keen interest in promoting the organization. He served as the first honorary vice-president of the Boy Scouts of America (William H. Taft was the honorary president) and authored the section “Practical Citizenship’ in its first handbook. “No one,” he wrote, can be a good American unless he is a good citizen.” Echoing Reinsch, he added: “every boy ought to train himself so that as a man he will be able to do his full duty to the community. I want to see the boy scouts not merely utter fine sentiments, but act on them.” Through truth, courage, and honesty they could play a positive role in governing their community.

Roosevelt also linked citizenship to character. Boys (healthy ones) should feel they will amount to something and in order to do so must have a productive nature. This was the first step toward good citizenship. The next one required civic engagement, for to do nothing disqualified a boy from good citizenship. He should seek to improve living conditions. This entailed, averred Roosevelt, not just effort, but courage. For example, they could—and should—take on “toughs,” bullies who prevented children from using a playground. They could also protect their surroundings by being taught to stop vandalism. Finally, they could beautify the country (and the park) by protecting the birds, trees, and flowers.

Roosevelt hammered home the centrality of character linking it to courage and masculine behavior. Boys, he asserted, must guard against becoming helpless, self-indulgent, and wasteful or they risked perpetual adolescence and not transforming into men. Repeatedly he invoked the term “courage”: courage to combat evil and courage to embark upon the righteous path. He must master “mind, eye, and muscle” and, at the same time, balance bravery with the compassionate qualities of gentleness, consideration, and unselfishness. Treat his mother and sister(s) well. Otherwise, he is a “poor creature” no matter what else he may accomplish.

Roosevelt used his experience in the Spanish-American War in 1898 as a way to preach the importance of good character to young boys. On the way to his famous, and near-fatal, South American journey in 1915, he sent a short message to James E. West, Chief Scout Executive of the Boy Scouts of America, which he stated was for all boys and not just scouts. Roosevelt introduced the subject of bullying by first recounting how he recruited his famed Rough Riders, for the Spanish-American War, noting that he only selected men who were “strong, hardy and brave” and “able to live in the open.” Yet he stated that he would exclude any man, no matter how brave, if he were a “quarrelsome bully” who would not honor the “army, the regiment and the flag.”

Roosevelt linked this odious character flaw to citizenship, a subject he often revisited in letters and speeches. “What was true on a very small scale in my regiment,” he posited, “is true on a very big scale of American citizenship as a whole.” In language that seems quite jarring by contemporary standards, Roosevelt expressed his impatience and exasperation with boys who did not live up to his prescribed standards of manliness. “I have no use for mollycoddles,” he pronounced, “I have no use for timid boys, for the ‘sissy’ type of boy. I want to see a boy able to hold his own and ashamed to flinch.”

A boy who was not “fearless and “energetic” was a “poor creature,” but he was even more detestable if he were a bully of smaller ones or girls. This was especially true if the bullying occurred in his own home, which Roosevelt condemned as “selfish and unfeeling.” He saw masculine virtues not as ends in themselves, but as a means for protecting the weak from the strong. Christian teachings shaped his thinking on this issue. “No man is a good citizen,” he told West, “unless he so acts as to show that he actually used the ten commandments and translates the Golden Rule into his life conduct.” It was a boy’s duty to intervene, on the playground, for example, to stop physical abuse against those unable to protect themselves. For Roosevelt, the boy or man who imperiously imposed his physical power over others or who cowered from aiding the victim of such abuse could not be a good citizen and contributing member to the community.

We should not lament the passing of notions that ridiculed and humiliated young boys for insufficient displays of manhood. Unfortunately, the baby was tossed with the bath. The very word masculinity has come in for derision and scorn, considered by some to be “toxic.” Woe to the lower or middle school boy who cannot sit still in class, follow directions or—worst of all—loses his temper on the playground or responds with aggression even if confronted by a bully. At best, he could be sent to the counselor, at worst his parents will be strongly urged to utilize the go-to panacea, Ritalin. Too many school administrators and teachers see young male behavior, which virtually all boys grow out of, as an existential problem to be suppressed through counseling and/or pharmacological solutions.

This change in political and popular culture is perhaps best evidenced in a famous 2013 Obamacare ad. In it, the selfless, civic-minded Boy Scout is replaced by “Pajama Boy,” a grown man drinking hot chocolate while wearing pre-adolescent footie pajamas, extolling the virtues of entitled cradle-to-grave government assistance. All rights, no responsibilities. Fortunately, we possess older, wiser, and salient models for children, such as Roosevelt’s, and can borrow from the best of them. Resilience, courage, and self-reliance remain worthy goals for young men—and young women. Far preferable to the displays of narcissism and performance art that characterize so much of social media.

As Reinsch counseled his young readers, citizenship was a precious gift. Like a garden, it requires constant care or its bounty could easily be irreparably lost. Implicitly, he was warning them that history is not linear and thus a sacred inheritance is not guaranteed to last in perpetuity.

Civic responsibility nourishes and maintains our republican experiment. It can be as simple as standing for the national anthem or as burdensome as reporting for jury duty. Without it, we devolve into atomized masses who self-silo into tribes, jockeying and scheming for public policies and funding that benefit them rather than prioritizing the national interest or common good. No collective identity, but instead a vast assembly of mutually-antagonistic “others.”

For generations, an important part of Roman boys’ education entailed hearing stories of famous selfless citizen-soldiers, the best example being Cincinnatus, who placed loyalty to the state over personal gain. During the republican period, the Romans famously and proudly proclaimed civis Romanus sum (“I am a Roman citizen”) which conveyed membership in a powerful and life-sustaining political entity. However, in the later republic when mercenaries and professional warriors gradually replaced citizen soldiers the notion of civic duty was undermined. When they lost pride in that cherished right, and the willingness to uphold and defend it, the gates were metaphorically, and later literally, opened to their declension and decline. Only a return to the pedagogy of the early 20th century, which taught children to extoll and to protect the sacred heritage of citizenship, can stave off a similar fate.