According to the Effective Altruism movement, no one should give to a local church, art museum, or school.

Toulmin and the Turn to Tolstoy

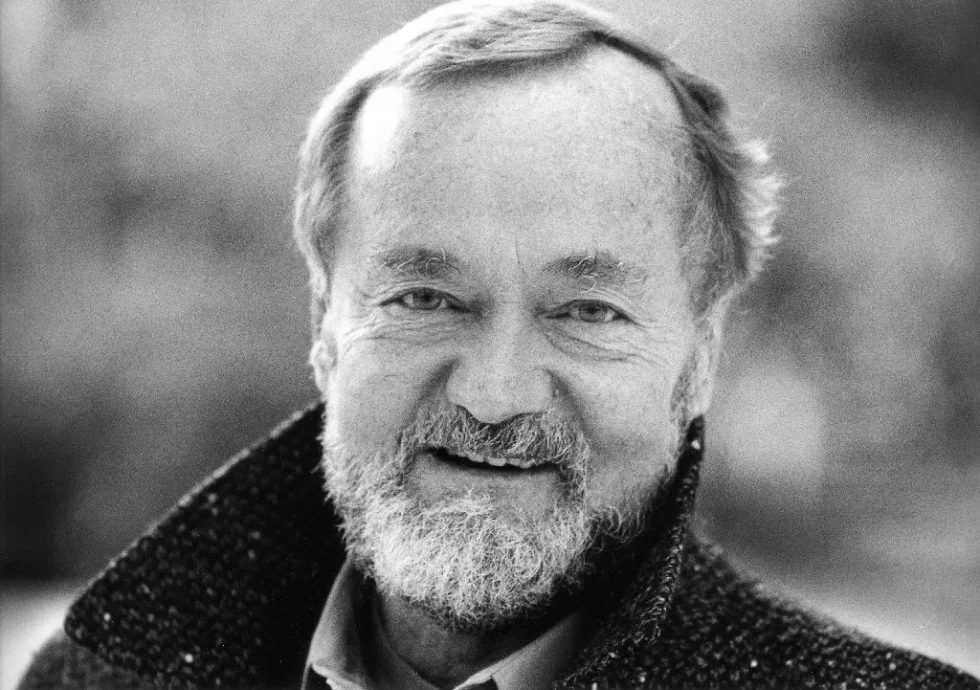

March 25 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of the late philosopher Stephen Toulmin. Toulmin raised serious questions about the ascendancy of the social sciences in recent history. To what degree and in what ways do social scientists such as sociologists, political scientists, and economists adequately describe, let alone explain, what is happening in human life? Cloaked in the mantle of “data,” they often claim to be providing more objective and reliable accounts, but what if the very methods and world views of the social sciences prevent them from seeing facets of life that we cannot afford to neglect? Suppose, for example, that literature has a vital role to play.

I met Stephen Toulmin in the 1980s, during my graduate studies in the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. During our first conversation in his office, Toulmin shared an eminently practical piece of advice: “The best thing you can say about a dissertation is that it is finished.” I got to know him much better through his teaching in Chicago’s Center for Clinical Medical Ethics. We read Alasdair Macintyre’s After Virtue, Martha Nussbaum’s The Fragility of Goodness, and especially Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, which seemed to be Toulmin’s favorite book. I can’t say how many times we saw his dog-eared copy of “Anna K” tucked under his wrist, along with the week’s The Economist.

Initially, Toulmin’s deep appreciation of Tolstoy struck this naïve young graduate student as odd. After all, I was studying Tolstoy with literary scholars such as Edward Wasiolek, Milton Ehre, and David Grene. Toulmin was a historian and philosopher of science, a theorist of reasoning and argumentation, and an ethicist. What was a man with that pedigree doing leading a seminar on Tolstoy? The answer lay, at least in large part, in an essay Toulmin had published in a bioethics journal in 1981. In “The Tyranny of Principles,” Toulmin warns against the danger of oversimplification in philosophy, the temptation to adopt solutions to moral problems that are, in Mencken’s words, “simple, neat, and wrong.”

In his writing and teaching, Toulmin argued forcefully against the twin terrors of absolutism and relativism, both of which he regarded as suffering from an excess of generality. Ethical reasoning must avoid a high level of theoretical certainty, simply identifying appropriate principles and applying them to cases. Likewise, it must avoid the relativist view that objectivity in ethics has been rendered untenable. What is needed, Toulmin held, is a return to real cases and the practical wisdom, generally born of long experience, by which appropriate approaches can be discerned. No moral principle is inerrant, but this provides no license to embrace utter cultural or personal subjectivity in moral reasoning.

Toulmin mined such insights in Anna Karenina. In our reading, we spent a great deal of time puzzling over the novel’s Biblical epigraph, “Vengeance is mine; I will repay,” and its celebrated first sentence: “All happy families resemble one another, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Under Toulmin’s tutelage, I found the epigraph drawing attention to the distinction between divine and human levels of understanding—we simply cannot know the full meaning or consequences of any of our choices. Toulmin, it seemed to me, wished to cultivate a healthy sense of respect for human finitude and extol the venerable moral excellence of humility, cognate of our very identity as humans.

The similarity of happy families I came to understand in several senses, a multivalence I believe Toulmin would have approved. First, it may allude to the relative peace and harmony of well-ordered lives, as opposed to the high drama of the miserable. Second, it may invoke an idea captured in the title of one of Flannery O’Connor’s works, Everything That Rises Must Converge—that is, that as moral excellence develops, good people tend to resemble one another more and more. Finally, Tolstoy may have been highlighting the differences in the attitude toward family life—the happy Levin and Kitty center their aspirations in the family, while the tortured Anna and Vronsky fail to understand and rebel against it.

We discovered that Toulmin took a rather dim view of the social sciences, and especially economics. Chicago economist Gary Becker, who would soon receive the Nobel Prize, was then arguing that human behavior—even perhaps the apparently self-destructive kind we see in Anna—can be explained as a rational form of utility maximization. While I never heard Toulmin refer to Becker, I know that Toulmin had his doubts about economics as a science. Adam Smith, for example, he regarded as an economist “among other things,” who focused not on universal and abstract analysis of human behavior but on specific aspects of what might be called the economic dimension of life.

Unlike Becker, Toulmin did not attempt to describe life’s moral dimension in terms of equations and grand principles but by focusing on particular cases and stories. So long as Levin searches for general principles by which to guide the operation of his estate or the conduct of his life, he is lost, in part because such theories cannot take into account anyone’s distinctive story. Instead of attempting to impose European theories on his peasants, he must immerse himself in their work, positioning himself elbow to elbow with those he seeks to control and learning from them. Toulmin was, in this sense, more of a bottom-up than top-down thinker.

Toulmin did not want to sketch out a grand theory on a blackboard but instead to welcome people, to get to know them and their problems, and in the context of such relationships to help us discern what our moral intuitions were calling us to do and to be.

Toulmin was following the path of Aristotle, who argued that a well-educated person looks “for precision in each class of things just so far as the nature of the subject admits; it is evidently foolish to accept probable reasoning from a mathematician and to demand from a rhetorician scientific proofs.” Ethics is not mathematics, and no amount of quantitative or algorithmic reasoning can substitute for the insights of someone with boots on the ground, who knows well the circumstances and the people involved. Anna strays so far from the path of goodness and happiness precisely because she forgets, or at least fails to see clearly, the true circumstances of her life.

Anna’s head is turned by the romance novels she reads and the appearance of a dashing young officer who is infatuated with her. She seems to forget, at least for long periods of time, that she is a wife and a mother. So, too, Vronsky, who has never known real family life, sees in Anna nothing more than an attractive woman whom he desires to possess, not a wife and mother. Levin, by contrast, wants nothing more than a family, and he falls in love with Kitty’s household as much as with her. Kitty, who has known nothing but a full family life, easily assumes the roles of wife and mother. She knows better than her husband the textures and rhythms of family life at its best.

It now seems clear why Toulmin so loved Anna Karenina. In it, he found a highly accurate portrayal of what it means to be a human being and the richest and most complete expression of the moral life. After decades of inquiry into ethics at the highest level, he found himself drawn most of all not to the treatises of moral philosophers, not even favorites such as Aristotle and Wittgenstein, but to the novel, and above all to Tolstoy. Before we can ask the question, “What should we do?” we must first learn to see, to listen, and to open our hearts to the real situations and people we encounter in everyday life.

Economics can function as a useful tool, but only so long as it minds its place. As a theoretical science, it can never rightly tell us what to do, and insofar as it presumes to represent a moral science, it does grievous and perhaps irredeemable harm to our moral sensibilities. Life is a good bit richer and more complex than any economic treatise can ever hope to account for. We may take classes with the economists, but if we aspire to live the best lives of which we are capable, we must live with the artists, who provide the fullest and most faithful portraits of human life. And foremost among them, in Toulmin’s view, was Tolstoy. Fixed ideas will not save us, and humility is a far greater virtue than certainty.

I found out much later that, while the Henry Luce Professor at the University of Southern California, his last academic post, Toulmin and his fourth wife, Donna, lived in a dormitory with over 500 students, where they hosted weekly dinners and turned their apartment into a refuge for anxious students, serving pizza and cookies until early in the morning. This is so like the Toulmin I knew. He did not want to sketch out a grand theory on a blackboard but instead to welcome people, to get to know them and their problems, and in the context of such relationships to help us discern what our moral intuitions were calling us to do and to be.