If the Supreme Court were to accept the plaintiffs' logic in Trump v. Hawaii, the judicial branch will gain new powers over defense policy.

Victory Formation

Football metaphors are often apt for politics and law, arenas in which two competing views vie to move the ball down the field, as it were, with incremental progress. Political parties are often chastised not to spike the ball at midfield—that is, to celebrate what they think is a touchdown when they’ve only advanced part of the way. When a lawyer gets desperate in court, he makes a Hail Mary argument, the long shot to try to win it all against the odds. And in football and lawmaking alike, no one seems to know what a catch is.

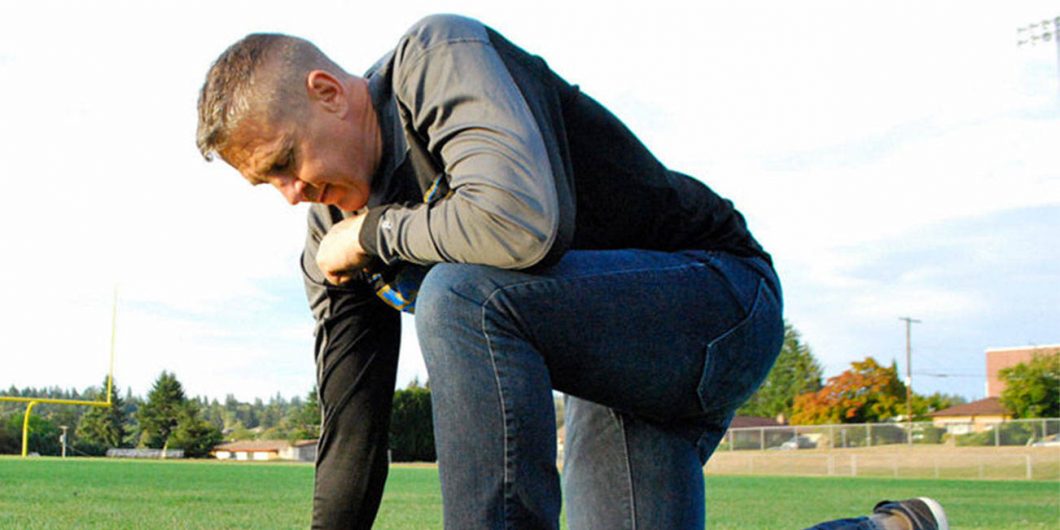

It could not be more fitting, then, that the case of Kennedy v. Bremerton School District involved a football coach at a Washington public high school who wished to kneel in prayer after games, and was fired for doing so. Kneeling is how the team in the lead bleeds the clock when the game is all but won. An offense that lines up for a kneel-down is said to be in “Victory Formation.” Americans who have long fought forces hostile to religion in public life can now do the same.

The Supreme Court ruled in Kennedy that a public school was not only not compelled to fire an employee for engaging in open acts of religious exercise, but was in fact prohibited by the First Amendment from doing so. Our Bill of Rights protects free expression and free religious conduct, even when it comes from public employees. Advocates for religious liberty cannot quite yet declare unconditional victory, as religious individuals still face obstacles to full participation in American life. But those seeking a healthier prevailing consensus on the relationship between church and state can assume Victory Formation. The “wall of separation” between church and state, which only prevented traditional faiths—never the new orthodoxies—from entering the public realm, is teetering. When it falls, the healing can begin.

Though the Kennedy Court could not technically overrule the bizarre Lemon test, invented in 1971 to ensure that government did not become “excessively entangled” with religion, it drove a stake through the heart of Lemon’s implied worldview. (The Court was not asked to overrule Lemon v. Kurtzman, and Kennedy was technically a Free Exercise case, Lemon an Establishment Clause case.) Justice Gorsuch, writing for the majority, repudiated the Court’s mid-20th century interpretation of the First Amendment, which relied on the conceit that America was a fundamentally secular society. We are not. We are, rather, a pluralist country, with pluralism encoded in our constitutional DNA. Those not trained to see the difference should study Justice Gorsuch’s argument closely.

It is telling that critics of Kennedy—and Carson v. Makin the week prior, which prohibited Maine from discriminating against religious schools in its generally-available education-subsidy program—have traveled a great distance from arguing that anything like an establishment of religion has occurred. Instead, they have embraced a militantly secular ethos, guarding the public square from any semblance of religious—that is, Christian—taint.

Prominent progressives quickly adopted a line of criticism equally embarrassing for its irrelevance as for its appearance of coordination. Wajahat Ali of the Daily Beast wrote that he was “looking forward to Muslim teachers praying w[ith] Christian students to Allah.” The Atlantic’s Jemele Hill begged, “Please let a Muslim coach try this and see what happens.” Radley Balko of the Washington Post tweeted that he was “trying to imagine the Fox News coverage if a Muslim high school football coach whipped out a prayer rug, knelt on the 50-yard line, and prayed after every game.”

A few small points: Coach Kennedy was allegedly fired for praying alone, though there were instances when some players voluntarily joined him. For all we know, Muslim coaches (or teachers) across the country have already prayed during breaks in the school day, but weren’t fired or sued. Fox News and the Supreme Court do not engage in the same analyses, because one is a cable TV channel and the other is the highest court in the land.

But the big point is this: Kennedy’s critics made no attempt to argue that a coach praying was tantamount to government establishment of religion. In fact, they did the opposite. By jumping to fantasies of a Muslim coach praying on the field, they admit that their position has nothing to do with actual state religion—that is, unless they actually think there is a risk of Islam becoming the state religion of Washington. This is not about “Establishment” at all. No one is worried that allowing a football coach to pray “establishes” anything, just as they wouldn’t worry that a Muslim coach praying “establishes” Islam as a state religion. It’s about driving traditional religion—particularly Christianity— from public life. Ali, Hill, Balko, and the many others who reacted similarly have merely projected their perception of Christianity onto what they imagine conservatives must think about Islam: not an actual threat to rights of conscience and free exercise for all, but an icky cultural force to be driven from the public square.

The dissent was less crass about it, but similarly confused. Rather than making any claim that an unconstitutional establishment of religion requires anything approaching an establishment of religion, Justice Sotomayor appealed to “our Nation’s longstanding commitment to the separation of church and state.”

Such an appeal sounds increasingly ridiculous for two reasons. First, the dissenting justices would deny the most basic exercise of the enumerated right of religious liberty—an individual, praying alone—in favor of an imagined gloss on the Establishment Clause. “Separation of church and state” is not a constitutional provision, and no projection of a “national commitment” would make it so.

Second, restricting traditional religious activity in the name of “longstanding concerns surrounding government endorsement of religion”—any religion—now sounds facially absurd. Public schools across the country have embraced (some openly, some less so) and begun inculcating belief systems bearing all the hallmarks of religious thought. Our constitutional jurisprudence contains little to guide our understanding of what precisely religion is, so taking an abstract view of why religion occupies its unique place in our constitutional order—both liberated and constrained—is instructive. Secularism, as a totalizing ideology containing assumptions about human nature and humans’ highest goods, may or may not meet the sociologist’s definition of a religion, but for the purpose of sorting out our First Amendment questions—putting “separation of church and state” in its proper place—it has no greater claim to state endorsement than any other -ism.

The outcomes in Kennedy and Carson represent the restoration of some of America’s defining principles in the face of hostile secularism that leaves no room for pluralistic coexistence.

The framers of our Constitution, particularly James Madison, believed religious liberty was an inalienable right because questions whose answers are unknowable cannot be pursued through coercion. The mysteries of the universe and humanity’s ultimate purpose within it are both too esoteric and too prone to facilitate strife when debate and argument run out—that is the nature of argument about transcendent goods. That is (at least a major reason) why the state is meant to get out of the business of coercing belief. Transcendence is for everyone to ponder on their own, and for all to pray and worship according to the dictates of their conscience.

With public institutions frequently (if unwittingly) inculcating beliefs about transcendent (and debatable) topics—for instance, the relation of human consciousness to the human body— attempting to prevent government “endorsement of religion” seems not neutral but sectarian. It is a vote in favor of the prevailing militant secularism that has reduced Christianity to second-class status in the hierarchy of American ethical systems.

It does not, as the dissent argues, protect students from the threat of coercion. It merely privileges one cultural force over another, on the basis that one explicitly involves God (forbidden!) and one does not (required!). Yet there is no reason to think that rights of conscience ought to depend on whether a belief system contains a deity or only a pantheon of deified concepts.

Healthier First Amendment jurisprudence need not embrace sectarianism of its own. Justice Gorsuch demonstrated his keen understanding of the better alternative in his majority opinion. “Learning how to tolerate speech or prayer of all kinds,” he wrote, “is part of learning how to live in a pluralistic society, a trait of character essential to a tolerant citizenry.” Our First Amendment’s great blessing is that it demands a robust form of state neutrality not geared towards secularism but pluralism. Rather than leveling down to strip all forms of weighty expression from the public square, the combination of the two Religion Clauses presents the possibility of leveling up. All citizens can—indeed ought to—encounter a diversity of views about the transcendent and the good. All citizens may contribute to that diversity, as a matter of right. No one may coerce another to adopt any one view. But all must learn to coexist. If our public schools cannot teach that crucial lesson of citizenship by example, they have lost sight of their mission.

Justice Gorsuch correctly went a step further, noting that such an interpretation of our Constitution is central to facing the great challenge of living in a heterogenous free society. “Respect for religious expressions is indispensable to life in a free and diverse Republic,” where encountering difference is a blessing if handled with mutual respect rather than hostility, “whether those expressions take place in a sanctuary or on a field, and whether they manifest through the spoken word or a bowed head.” To have a nation built not on color or tribe but on dedication to the principles of ordered liberty requires such an attitude. And it is what makes America blessedly unlike the other nations of the world.

The outstanding outcomes in Kennedy and Carson are more than just progress after decades of judicial fumbling. They represent the restoration of some of America’s defining principles in the face of hostile secularism that leaves no room for pluralistic coexistence. Justice Gorsuch’s critics would be wise to embrace pluralism that has room for Christians—and yes, Muslims and Jews and other religious people too—rather than using the Constitution as a cudgel against them. Being a sore loser is a bad look when your opponent is lining up to kneel down.