A review of thirty years of scholarship on why judicial impeachment - even on partisan grounds - is permissible.

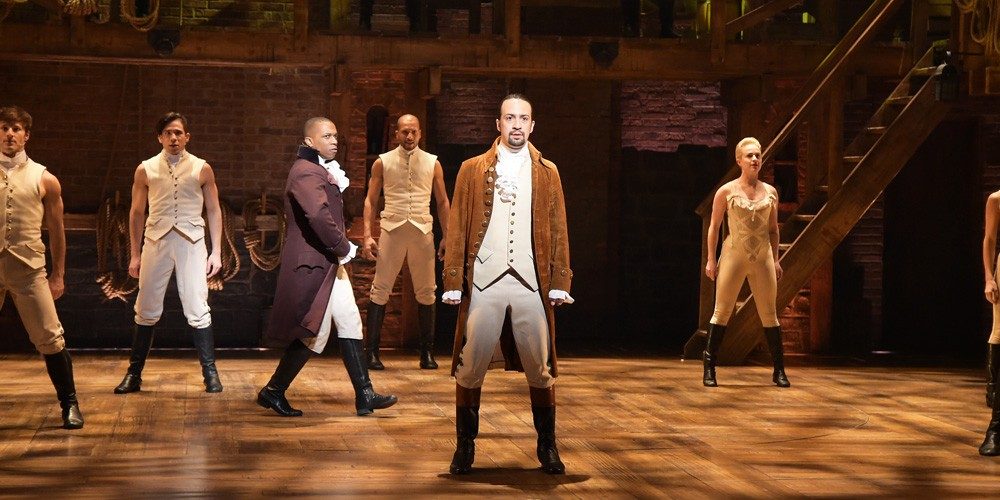

“Who Tells Your Story?”

Who expected it? A world-wide pandemic, recurring food and supply shortages, massive unemployment, widespread violence and lawlessness, deep political disagreement and distrust, feckless leadership, and a general breakdown of our political institutions.

To many Americans, the current state of affairs seems surreal, if not apocalyptic. As we fret about the dangers of George Orwell’s 1984 our country is spinning towards George Miller’s Mad Max. What we need now is sober realism wedded to the right ideals. We need Hamilton. We don’t mean Hamilton the man—although we could sure use a statesman like Alexander Hamilton right now—we mean Hamilton the musical.

We will admit, when the musical first came out in 2015 we were skeptical. A rap musical dramatization of the American Founding? Wouldn’t this musical be a boring sermon in political correctness?

But with nine children under the age of 20, it is difficult to avoid completely the latest pop fads, and songs from the Hamilton soundtrack eventually made it onto the song list for long family car trips. We found ourselves first surprised, and then positively delighted by the creativity, thoughtfulness, wit, and sheer excellence of the songs.

When the musical was released for streaming on July 3, we were excited to see it. But we did not expect it to speak so directly to the serious challenges we are facing today: Deep racial polarization, a breakdown of civil discourse, and a full blown identity crisis about what it means to be an American citizen. As Alasdair MacIntyre and, more recently, Wilfred McClay have pointed out, identity, whether personal or political, is rooted in a true narrative about our origins, our heroes, and our animating ideals. America may be a “creedal nation” dedicated to the self-evident truths of the Declaration, but the stories, the flag, the anthems and songs, the days of Thanksgiving and prayer, and yes, even the statues—in short, culture and art—give these ideas life and make them our own.

In other words, to quote the final song of Hamilton, “Who tells your story?” And how is it told? Is there an alternative to the extremes of the 1619 Project’s claim that America is systemically racist from the beginning and the Pollyannaish blood and soil nationalism of Trump’s tweets? Without sermonizing, Hamilton shows us how art can still tell “our story” well, and in ways that unite instead of divide. It’s impossible to do justice in prose to the creative brilliance of Hamilton, but here are three points worth noticing.

Telling the Truth about Hamilton—and America

First and foremost, Hamilton is a truly great work of art which compellingly tells the truth about Alexander Hamilton personally, and America politically. In form, Hamilton is a feast of sound and sense, with its playful pageantry, gripping plot, creative lyrics, clever humor, musical breadth, stunning choreography, and impressive acting.

In substance, the story Hamilton tells is humanly compelling. Though it includes myriad historical details and is largely historically accurate, Hamilton is not history, but art. Great art does not set out to moralize or make a point, and art that does so—in addition to being bad art—usually fails to influence culture deeply. Rather, good art tells the truth—not literal truth, but metaphysical truth. By imaginatively shifting perspective, art can show us depths of reality that mere sensory or factual knowledge can easily miss.

And the metaphysical truth is that human nature is neither depravity nor innocence, victimization or agency, but the drama of being constantly threatened by the one even as we are irresistibly drawn to the other. Hamilton’s “realistic patriotism” works against today’s cancel culture by showing the messy reality of a principled political life, which, despite mistakes and problems, was nonetheless honorable. Likewise, Hamilton shows that America’s past does not have to be full of perfect “saints” to be fundamentally good and honorable.

The life of Hamilton is impressive on its own. As the opening song of the musical puts it: “How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore / And a Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot / In the Caribbean by providence impoverished / In squalor, grow up to be a hero and a scholar? / The ten-dollar founding father without a father / Got a lot farther by working a lot harder / By being a lot smarter / By being a self-starter…” No blaming, shaming, or self-victimization here.

Born an illegitimate child (a condition with significant legal, social, and economic disadvantages in Hamilton’s time) in the Caribbean, abandoned by his father and then orphaned at an early age, Hamilton went on to become one of America’s most important Founding Fathers. Among other things, he authored the largest portion of The Federalist Papers, designed the nation’s financial system while serving as the first Secretary of the Treasury under George Washington, and helped organize the Federalist Party.

Hamilton was no saint, however. Married with eight children, Hamilton had an extramarital affair with a married woman, which he sought to cover up by bribing the husband. And his constant political machinations earned him the enmity of many, and ultimately led to his death in a duel at the hands of Vice President Aaron Burr.

But Hamilton also reconciles with his wife Eliza. Her anger in “Burn” and then forgiveness in “It’s Quiet Uptown” are powerful moments in the musical. And his dedication to America and American ideals is clearly contrasted throughout the play with his antagonist Burr, who is shown as a dishonorable man of unprincipled personal ambition and, ultimately, a failure.

If political identity is constituted by story, then this question becomes of paramount political importance. Today, America is deeply divided over this question, and so we are divided in our very identity.

As with Hamilton’s personal life, so with America: The play’s depiction of the founding defies the simplistic, black and white categories of the cancel culture on the one hand, and an uncritical patriotism on the other. According to Hamilton, the American founding is imperfect but good. It shows us that the founders regarded slavery as unjust and contrary to the principles of the American founding, rather than as an expression of those principles. Slavery is a horrific spot on the goodness of the founding, but forgiveness is as necessary in politics as in marriage. In dramatizing the tension between principle and practice in the founding, Hamilton helps to correct the false and mischievous history of Justice Taney in the infamous Dred Scot decision which continues to dominate the narrative of the radical left.

One of the best instances of this is “Cabinet Battle #1,” which consists of a debate over Hamilton’s financial plan. Thomas Jefferson argues, “Don’t tax the South ‘cause we got it made in the shade / In Virginia, we plant seeds in the ground / We create, you just wanna move our money around.” Hamilton delivers a delicious response to Jefferson’s agrarian populism that simultaneously unveils Jefferson’s hypocrisy while also leveling a dig at the French Enlightenment:

A civics lesson from a slaver, hey neighbor

Your debts are paid ‘cause you don’t pay for labor

“We plant seeds in the South. We create.” Yeah, keep ranting

We know who’s really doing the planting

And another thing, Mr. Age of Enlightenment

Don’t lecture me about the war, you didn’t fight in it.

Building a Bridge

Secondly, Hamilton helps build a bridge between blacks and whites in America by fusing the core story of American identity to a largely (though not exclusively) black cultural idiom. This is the genius of Hamilton. (Although a charmingly narcissistic and sadistic George III almost steals the show with his more conventional show tune “You’ll Be Back.”) Unlike the extreme voices on the left and right, it is a constructive, not a destructive, creative enterprise.

We can see this cultural marriage in “Cabinet Battle #1.” Delivered with the assertiveness, verbal gymnastics, syncopation, and “voice merging” typical of hip hop and rap (Nathan’s favorite allusion is to Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message,” which reminded him of his futile efforts to breakdance in the early 80’s), the song nevertheless compellingly conveys the seriousness of the issues and ideas, the personal and political division that always make compromise so difficult. In doing so it extends the conventional boundaries of both rap music and politics.

Hamilton certainly honors the founding genius of America, the heroic risks, the difficult and often messy compromises that had to be made, and the great challenges of governing a new and diverse nation. But by telling this story in a black cultural voice, Hamilton literally binds the African American experience into the larger American one, claiming the American founding story for blacks of our generation, while forever enshrining in American culture more generally some of the greatest modern contributions of black American art.

Maintaining Honor under the Law

Thirdly, Hamilton shows that the greatest challenge of political life is not achieving liberty, but preserving it. The two acts of the musical are organized around the two main moments of the American Founding, the Revolutionary period (Act One) and the Constitutional period (Act Two). There are different virtues required for these moments, and they are in some tension with one another.

Put most simply, the first moment requires assertiveness and courage, while the second requires moderation and restraint. How does the lawlessness of the first moment get transformed into the law—abidingness of the second moment? It is relatively easy to tear down and destroy, and very difficult to build things that will last. As George III puts it in his wonderfully sardonic humor “What comes next? / You’ve been freed / Do you know how hard it is to lead? / You’re on your own / Awesome, wow! / Do you have a clue what happens now?” Or, as Washington tells Hamilton when he can’t get his financial plan through Congress, “Ah, winning was easy, young man, governing’s harder.”

Early in the musical a young Alexander Hamilton newly arrived in New York sings “Hey yo, I’m just like my country/ I’m young, scrappy and hungry, / And I’m not throwin’ away my shot.” In the song he expresses his ambition and assertiveness in the cause of the Revolution (a cause which alludes to slavery, as does much of the musical): “Let’s hatch a plot blacker than the kettle callin’ the pot / What are the odds the gods would put us all in one spot / Poppin’ a squat on conventional wisdom, like it or not / A bunch of revolutionary manumission abolitionists? / Give me a position, show me where the ammunition is” (My Shot).

Yet the lead image used in the advertising for Hamilton shows a silhouette of Hamilton precisely throwing away his shot, as he points his finger up into the air like a gun. This is the moment of Hamilton’s fateful duel with Vice President Aaron Burr which ended Hamilton’s life, and Burr’s political career. Dueling, of course, is a throwback to a time when injury to honor and reputation are taken as seriously as injury to person and property. (The Founders themselves mutually pledge their “sacred Honor” in the Declaration of Independence). And by participating in the duel, Hamilton acknowledges the claims of honor.

But dueling also reflects a breakdown in the rule of law, and is also a step on the path to vigilante justice, a cycle of violence which leads to anarchy. By participating in the duel but refusing to shoot Burr, Hamilton seeks to affirm the claims of honor and the rule of law. In the eyes of Hamilton, this self-restraint, is the greater, more manly achievement.

In Hamilton the question is repeatedly raised, “Who tells your story?” If political identity is constituted by story, then this question becomes of paramount political importance. Today, America is deeply divided over this question, and so we are divided in our very identity. There is something gnostic in the extremes which see America exclusively in terms of light or darkness, innocence or guilt, black or white. Hamilton shows us that our story does not have to be perfect to be true, or to be both beautiful and good.