We use metrics to assess everything, but measurement does not always equal wisdom.

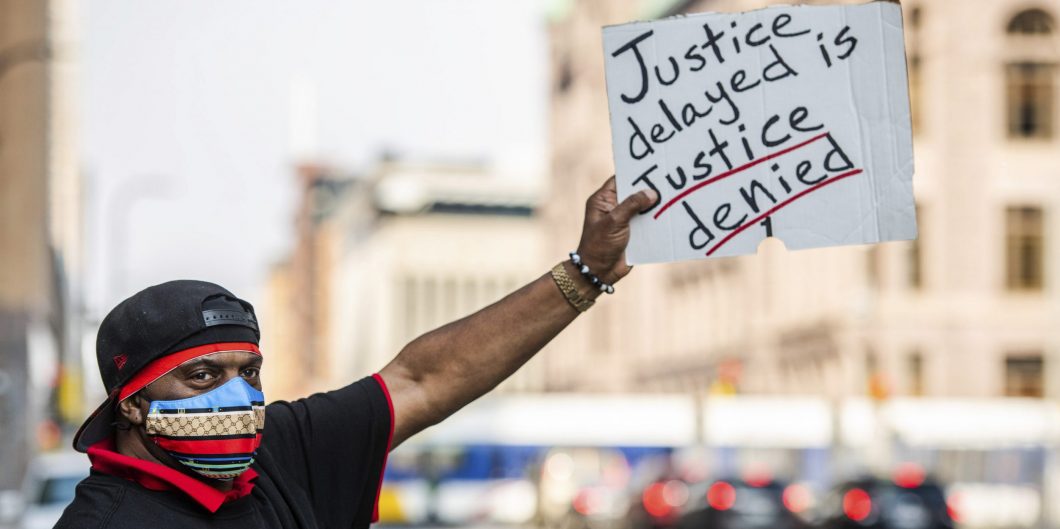

Will the Jury Deliver Justice?

The jury has been chosen, and the trial will soon begin. Derek Chauvin, formerly of the Minneapolis police, stands accused of murder, in connection with the death of George Floyd last May. Here in the Twin Cities, we are hoping for the best and bracing for the worst. As spring slowly creeps in, our downtown is sporting a new look, with barbed wire fencing and an alert National Guard.

These cautionary measures are not excessive. History suggests that racially charged trials can end quite badly. Everyone remembers 1992, when the acquittal of four Los Angeles policemen sparked a punishing wave of destruction that remains, to this day, the most costly episode of civil unrest in all of American history. Echoes of that same fury were heard in November of 2014, after the Ferguson Grand Jury chose not to indict Officer Darren Wilson. Baltimore, Chicago, Baton Rouge, and Dallas are among the many other cities that have weathered this storm. In the decades since the LA riots, the terminology has shifted, but it’s wise to be prepared. Here in the Cities, we’re hoping to avoid a repeat of last summer’s “mostly peaceful protests.”

The Shadow of the Past

Riots are not the jury’s concern, however. They have another important task. Is it too much to hope that our citizenry could accept a fair verdict, giving justice both to Derek Chauvin and to George Floyd?

This isn’t the first time that Americans have tuned into a high-profile trial, which was presented by many activists as a racial-justice morality play. Two haunting precedents loom large in the background, both of which forced us to confront similar questions about law and order, moral responsibility, and the dark legacy of slavery. Both, unfortunately, were decided wrongly. Both of them left tears in our social fabric that were never truly repaired. If race relations in America have worsened over the past few decades, that has something to do with the trials of Rodney King and OJ Simpson.

The policemen who beat Rodney King were tried in the peaceful and suburban Simi Valley, ostensibly because officials hoped to avoid a disruptive media circus. Only 2% of prospective jurors were black, and none of those were chosen. Evidently, this mostly-white, middle-class jury bought the argument that King was dangerous and aggressive, and mostly himself responsible for the savage beating he received.

In some respects, the OJ Simpson trial seemed eerily like a mirror image of what happened in Simi Valley. Before the trial, defense attorney Johnnie Cochran famously bragged that even “one black juror” would be enough to get him a hung jury. He got nine, and Simpson was acquitted. At the time, substantial majorities of white Americans believed Simpson was guilty, and that the verdict had been racially motivated; only about a quarter of black Americans believed that Simpson had murdered his wife. (Interestingly, those numbers are rather different today.)

There is a tragic irony to each of these cases. Both juries seem to have been unduly influenced by a broader national narrative, and especially by a desire to vindicate a larger group that they saw as sympathetic and deserving. In fact, each verdict served to undermine that group in the eyes of the general public. The LAPD staggered away from the Rodney King affair with its reputation in shambles, while Simpson’s trial seems to have marked a turning point for many Americans in their attitudes about racial justice.

When we reflect back on Rodney King and OJ Simpson, we may be tempted to conclude that juries have passed their time. That would be a mistake. Norma Thompson articulates many of the reasons in her book, Unreasonable Doubt: Circumstantial Evidence and the Art of Judgment.

The Task of Juries

Unreasonable Doubt offers a most unusual argument. For one thing, it focuses on the hazards of unjust acquittals, when most reformers in the criminal justice world are more concerned about unjust convictions. There are reasons, to be sure, for focusing on the unjustly condemned. For every guilty man who is freed by an over-fastidious jury, it seems likely that there are multiple innocents who accept pleas under pressure from a harried prosecutor. Still, the former case can also be quite harmful, as we saw in the above-mentioned trials. Thompson understands this keenly, because she served as the foreman for a hung jury that ultimately released a man who, in her view, was clearly guilty of murder.

A jury… is perpetually threatened by two enemies: the poet, and the sophist. The former eschews reason because it he is more interested in spectacle and emotional satisfaction. This is especially dangerous in the context of a trial because it does have many of the features of a morality play, and that high drama and symbolism may condition us to expect a well-crafted narrative, complete with a climax and satisfying conclusion.

Juries are fallible, because they are made up of human beings. Because they generally are not experts in any of the relevant subjects, they may not always be in a position to judge expert testimony reasonably. Nevertheless, juries play an important role in our justice system. Already, experts dominate the justice system, authoring and (mostly) enforcing the statues that govern our shared life as citizens. Juries provide a point of contact with the ground, forcing attorneys to convince fellow citizens, even as citizens are required to contribute something to the maintenance of law and order. Unreasonable Doubt is at times quite moving for showing how demanding this task can be. Professionals may become desensitized to the grisly details of crime, but most jurors are not. They feel the weight of the responsibility that has been given to them, either to release a criminal or to condemn him. Years after the trial, Thompson is still haunted by the outcome. She viewed it as a failure, plain and simple, and despite lamentable errors by the police and other actors, she saw the jury as the main problem.

Most of the jurors in Thompson’s case were convinced of the guilt of the accused. Even the holdouts seemed to agree that it was highly probable that he was guilty; their complaints were petty and argumentative. One juror obsessed constantly over his conviction that eyewitness identifications (even from three separate people) were unreliable. They complained because the probable murder weapon, a cinder block, had left only a partial imprint on the victim’s skin. They would have preferred a puzzle-perfect rectangle. None of these recalcitrant jurors had a plausible alternative theory to offer, of a sort that could explain either the damning evidence or the crime itself. It seemed to Thompson that they were cranky and mulish simply because the task of deliberation was so hard. They wanted it all to be as simple and straightforward as a child’s shape-sorter.

Serious deliberation calls for a courage and moral maturity that many people unfortunately lack. A jury, as Thompson explains, is perpetually threatened by two enemies: the poet, and the sophist. The former eschews reason because it he is more interested in spectacle and emotional satisfaction. This is especially dangerous in the context of a trial because it does have many of the features of a morality play, and that high drama and symbolism may condition us to expect a well-crafted narrative, complete with a climax and satisfying conclusion. Those expectations make it difficult to engage in the messy job of applying the law to the actual deeds of real people. In an age that is saturated in criminal-justice movies and television dramas, this danger is particularly serious. Attorneys like Cochran have certainly demonstrated how effectively showmanship can be used to draw a jury’s eyes away from plebeian things like facts and evidence. This sophistical talent can be useful for building a defense attorney’s career, but it is ruinous to the cause of justice.

Compared to the poet, the sophist is not quite so averse to reason, but he lacks the moral seriousness needed to heed the force of his own words. In the Platonic dialogues, Socrates regularly unseats his opponents by demonstrating their inability to live by their own words. That kind of moral unseriousness can be deeply problematic for a jury, simply because the subject at hand is exceedingly serious. Lives can be saved, ruined, or unexpectedly redeemed, by the outcome of a trial. This should be a daunting prospect to every person summoned for jury duty. Living in a virtual age, we are all quite accustomed to voicing opinions in contexts where they carry no consequence. How many of us are prepared to step into a situation where our opinion is extremely consequential?

One needn’t be specially knowledgeable, intelligent, or eloquent to be an excellent juror. The job does require a high level of moral maturity, however. Can the city of Minneapolis find twelve virtuous men to serve on Chauvin’s jury? Can we at least find twelve decent men?

Third Time a Charm?

Chauvin’s jury will need keen powers of deliberation, because his case is exceedingly strange. Controversial police killings have become a semi-regular occurrence in America, but this one is atypical in multiple ways. Usually, a tragic police encounter takes place in just a few fateful seconds. If video footage exists, we almost have to watch it without blinking, for fear of missing the critical moment. At the same time, most police shootings are relatively easy to understand. One viewing is enough to get an intuitive sense of what happened. Perhaps an officer or bystander was genuinely threatened, or maybe the officer was skittish and trigger-happy, or maybe he lost emotional control and hurt someone unnecessarily. Most controversial police killings fit one of those three molds. Even when we condemn the relevant behavior, we can usually understand it. Chauvin’s behavior is far more perplexing.

The video of Floyd’s death is painful to watch precisely because it is excruciatingly long. For minute after agonizing minute, Floyd weeps and begs while Chauvin sits impassively with his knee on Floyd’s neck. The scene is frankly baffling. What does this 19-year police veteran think he is doing? We should note in fairness that Floyd resisted arrest, and that his strength and size made it difficult for the officers to wrestle him into their squad car. That may partially explain why Chauvin chose to subdue him more forcefully. As the agonizing seconds tick by, however, comprehension fails. Floyd is unarmed and handcuffed, and has been lying on the ground for minutes without struggling. There are three other officers present, available to help. Was Chauvin waiting for even more backup to arrive? He doesn’t appear to be overcome with emotion, but it is hard to think of a good reason for subduing a desperate man for so long.

No doubt the jury will be forced to watch this sequence multiple times, but it will not truly answer the hard questions. What was happening during these crucial five minutes, in Floyd’s body and in Chauvin’s mind? The case will probably turn on those two points. At least, it should turn on those two points. It will be up to the jury to ensure that it does.

Because these two questions are genuinely quite hard, jurors may be tempted to ignore them, treating the trial instead as an opportunity to rule on some other question, on which they have stronger views. Does the Minneapolis Police Department need more discipline in its ranks? Do black men get a fair shake in American life? Like Thompson’s Platonic poet, jurors could view the video as an allegory for white America’s brutal and merciless treatment of underprivileged black citizens. Or, they could take revenge on the rioters who burned their city last summer by acquitting Chauvin entirely, regardless of what the trial shows. In truly sophistic fashion, they might rule with an eye to avoiding further riots, tossing the mob a victim for the sake of protecting the city.

A virtuous juror will do none of those things. Learning from the ugly precedents of King and Simpson, she will judge the Chauvin case on its own merits, based on the available evidence. Emotional trials often end badly, but if the jury does its job conscientiously, there is always a real possibility that this one could end well. Let us hope against hope that these twelve men and women can deliver justice, for Derek Chauvin, George Floyd, and the United States of America.