It all started when the spiritualist guru of the Trump family revealed to the Trumps the secrets of mind-over-matter.

The Essential Emerson

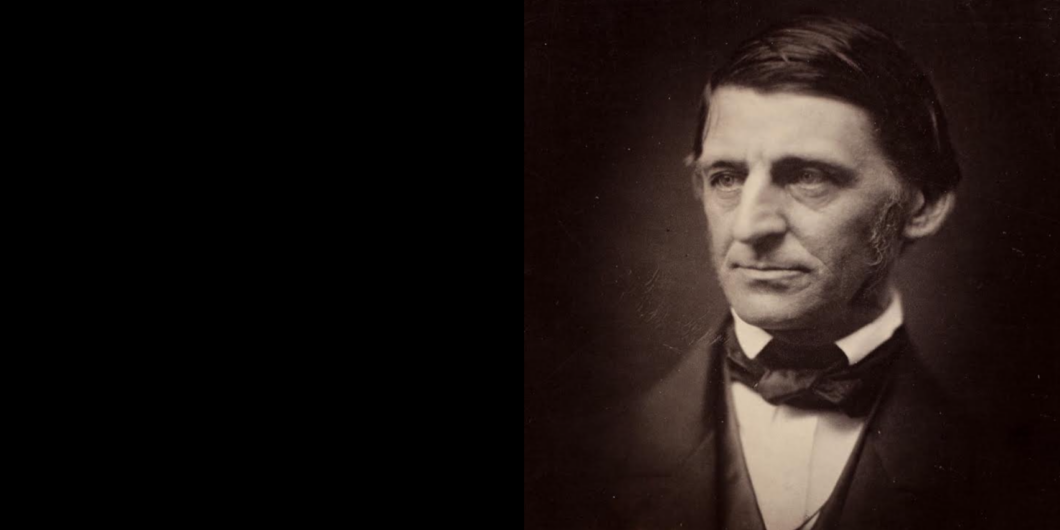

We all have guilty pleasures. Mine is Ralph Waldo Emerson.

A proud Southerner, I’m not supposed to like him. His Southern contemporaries William Gilmore Simms and Edgar Allan Poe lambasted him. Later, Southern poet and literary critic Allen Tate called him the “Lucifer of Concord” rather than his usual moniker, the “Sage of Concord.” Emerson’s Yankee sensibilities—his capitalism, metaphysical idealism, individuality, and spontaneity—contrast sharply with the Southern agrarian values of rootedness, tradition, hierarchy, and religion.

But I can’t help myself. Emerson is exhilarating.

So is his latest biography, Glad to the Brink of Fear. The author, James Marcus, admits that this “book took longer to write than planned,” possibly to approximate the lively yet oft-impregnable prose of his subject. But it was worth the wait.

Emerson’s life isn’t uncharted territory, so Marcus must map it afresh. He doesn’t do so chronologically, tracing Emerson’s life from childhood to death. Instead, he jumps from period to period, inserting himself into the text as the colloquial, first-person narrator (“I am writing these lines on a December afternoon,” he begins one chapter, “surrounded by tall, gray, columnar trees that have lost their lower limbs and resemble the masts of ships.”)

The portrait that emerges is of Emerson the paradox: a pedigreed man who articulated the democratic impulse; an urbanite who channeled nature; a nonconformist champion of individualism and self-reliance, celebrating the “infinitude of the private man,” yet also highly gregarious and social, fostering constructive relationships with numerous literary luminaries including Henry David Thoreau, James Elliot Cabot, Frederic Henry Hedge, Margaret Fuller, and, across the pond, as it were, Thomas Carlyle.

Despite his reputation for elation and joy, he endured profound grief, having suffered the loss of many loved ones. “He was,” says Marcus, “the oldest of five Emerson brothers, the others being William, Edward, Charles, and Bulkeley. (Another brother, John Clarke, had died in 1807 at the age of eight, while Emerson’s two sisters, Phebe and Mary Caroline, both perished as toddlers.” Besides these, his father passed away when he was seven. His brothers Edward and Charles died in their thirties. His first wife, Ellen, succumbed to tuberculosis at age 20, and his first son, Waldo, died of scarlet fever. The list goes on.

Pioneering a novel approach to literature, one that set Americans apart from European convention, Emerson drew inspiration from the giants of the past, “aligning himself with a long philosophical tradition, going back as far as the fifth-century thinker Dionysius (or, confusingly, Pseudo-Dionysius), who declared that beauty and goodness were basically the same thing.” His essayist antecedent was Michel de Montaigne.

While William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (both of whom Emerson met) may have anticipated Emerson, his writing was distinct, capturing the electrifying originality of the American project. He reflected the dynamic ethos of a country expanding westward, embracing new technologies, and exploring innovative forms of commerce.

Marcus calls the essay Nature “the beginning of American literature,” a designation sometimes reserved for Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. This claim is bolstered by the specific demand of Emerson’s era for the type of entertainment he provided, namely sermon-like speeches or professional oration. Marcus dubs Emerson “the itinerant lecturer.”

Emerson’s promising early career in ministry shifted to active participation in the burgeoning transcendentalist movement after he rejected the validity of the Lord’s Supper, making it impossible for him to lead a church. Transcendentalism didn’t oppose divinity but found it in intuitive communion with material nature rather than institutional religion. It has many definitions, but its “core,” according to Marcus, is “to be ourselves—and to be truthful at any cost.” This characterization is adequate so far as it goes but fails to encompass the emotional and mystical elements that distinguish this synthesizing philosophy.

Like many literary biographies, Marcus’s engages in exegeses texts written by the subject. Here, for instance, are surface-level analyses of the essays Nature, Self-Reliance, and Friendship. They’re enjoyable, unlike academic “interrogations,” because they enliven the narrative and avoid the tortured language and activist, presentist obsessions with race, class, and gender debasing once-respectable journals. However, Marcus seems overly eager to associate Emerson with queerness or homoeroticism, despite slim evidence that Emerson had any such inclinations.

The flux and flow of Emerson’s frolicking syntax is not unlike lived experience with its ups and downs, waxing and waning, highs and lows.

Emerson’s poetry hasn’t won the lasting esteem that his essays have. Marcus points out that, at the time of Emerson’s writing, “the essay was still a sketchy item in Anglo-American letters, mostly written and read on the fly, not regarded as a top-drawer literary genre.” If Emerson’s essays seem disjointed, with abrupt transitions, it’s because he crafted them from journal entries, indexed by topic, and adorned them with poetic devices (rhythm, rhyme, alliteration, assonance, euphony, metonymy, metaphor). The result was awesome, as if one were beholding diamond nuggets mined from a deep and rich soil of text.

It isn’t easy to determine what Emerson truly believed. His view of the universe as “self-adjusting, self-correcting, always moving toward a divine equipoise” resembles Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s conception of the common law as an organizing complex evolving from the accumulated, countless decisions of numerous judges. Both envision systems—one spiritual, the other adamantly secular—that naturally gravitate towards balance and order. Interestingly, Holmes attributed his future accomplishments to Emerson, underscoring their intellectual connection. “If I ever do anything,” Holmes allegedly told him, “I shall owe a great deal to you.”

A review, due to space constraints, necessarily overlooks important figures and events. In this case, notable omissions include Emerson’s marriage to Lydia Jackson, the influence of his Aunt Mary and Achille Murat, the theological controversies stirred by his (in)famous Divinity School Address, and his probable Alzheimer’s disease. But the matter of slavery shouldn’t be ignored because it figures so prominently.

Emerson initially dismissed the abolitionist movement as “a soapbox for virtue-signaling egomaniacs,” Marcus suggests, before the “slow awakening of [his] political conscience.” The site of a slave auction “lodged in his memory” when he was a teenager, and his “schoolboy” journals condemn slavery while nevertheless registering “speculations about racial hierarchy.” He did not suitably acknowledge the North’s complicity in slavery even though he was “certainly aware of the economic embrace that united the two regions.” Having early disapproved of abolitionists, he began to support them after meeting them because he admired heroes and perceived them as such. Eventually, he spoke before abolitionist audiences. Maybe he caught the sectional fervor and aligned himself with his surroundings. In any case, he enthusiastically committed to abolitionism.

Marcus submits that Emerson “lived and died by the sentence.” The flux and flow of Emerson’s frolicking syntax is not unlike lived experience with its ups and downs, waxing and waning, highs and lows. The late Richard Poirier and Harold Bloom portrayed Emerson as a visionary struggling with the inability of language to render the magnitude or intensity of actual feelings. Marcus, too, notices Emerson’s frequent recourse to expressions of ecstasy, stating, “A genuinely ecstatic experience cannot be conveyed via understatement. It demands that we push language to its maximum capacity—to the point at which it starts to fail.” Poirier had a name for this animated gush, superfluity, which, for him, was positive rather than negative.

Even those with rudimentary knowledge of Emerson recall his memorable sayings:

“To be great is to be misunderstood.”

“The ancestor of every action is a thought.”

“Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.”

“Every artist was first an amateur.”

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

His aphorisms may have befallen the desensitizing effects of familiarity, yet they remain part of the American vocabulary, easily recalled when rousing words are needed. We may never fully grasp Emerson’s meaning of “transparent eyeball,” but it evokes a sense of radical receptivity—opening one’s mind to diverse ideas, letting them flow through with sublime energy.

This radical openness may frustrate some readers or make Emerson seem inconsistent—but it is really one of the great strengths of his style. Rather than dictate the meaning of an essay to his readers through bold theses or rigid logic, Emerson makes them wander with him on a meandering journey. Reading his essays means thinking alongside him. It is a delightful opportunity to speculate about new vistas and contemplate new ideas.

However engaging Emerson’s captivating style and clever phrasing are, his denigration of Southerners and arrogant claims of New England superiority (he said New Englanders possess “a thousand times more talent, more worth, more ability of every kind” than Southerners) are difficult to overlook. Yet I’m living proof that appreciation for his work and life is possible, even among Southerners. I concur with Marcus: “Wisdom is what Emerson has to offer us, frequently disguised as a parable, dream, diatribe. To ignore him is to ignore something essential.”