Key Trump policies advanced classical liberalism, but his association with them may damage them in the long run.

Beauvoir's Best Insight

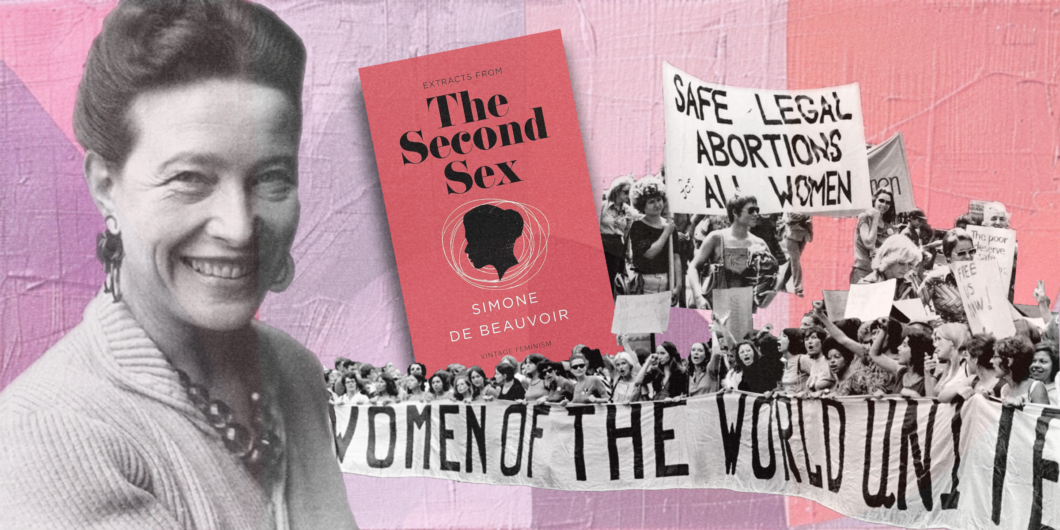

Simone de Beauvoir identified as a communist for much of her adult life. She was a firm advocate for abortion and artificial contraceptives. As noted by Emina Melonic in her lead essay, she had a kinky sex life and questionable taste in men, as well as a pronounced hostility to maternity. As a conservative, pro-life, anti-communist, Catholic mother of five, I am obviously supposed to revile Beauvoir. But actually, reading through her most famous work, The Second Sex, I find some segments quite compelling. When I first picked it up some years ago, I was startled to find that some passages tracked my own considered view rather well.

It’s probably impolitic to admit this right now. The right’s own “feminism wars” are currently raging, with sex-realist feminists squaring off against a more reactionary camp that decries all feminism as a colossal, possibly demonic, mistake. In such a climate, I recognize that praising a deeply unsympathetic figure like Beauvoir will tell some critics all they need to know. I can only reply that it’s not my fault if baby-hating communists get at least a few things right.

Beyond that, though, a book like The Second Sex may be more helpful to us if we can pinpoint with precision where Beauvoir went wrong. Because she did go quite badly wrong. In the end, I agree with Melonic that she was deeply narcissistic, with a massive chip on her shoulder. This can happen when a person correctly perceives a certain kind of injustice in the world, but fails to get perspective on it. Insofar as The Second Sex is properly read as a cautionary tale, the lesson may apply to many groups, not just women.

The clearest way to explain this is by laying out Beauvoir’s view in stages, supplemented by my own commentary. I will ask three questions, and reply to each with a summary of Beauvoir’s view, followed by my own assessment of that view. (I will signal the transition with a simple “I think.” I was tempted to lead with “Respondeo,” but I restrained myself.)

Why does Beauvoir see woman as “the second sex”?

Woman is the second sex because, as Beauvoir sees it, the masculine has consistently been viewed across history as the norm for human nature as a whole: “Humanity is male and man defines woman not in herself but as relative to him.” Historical books on anatomy treat the masculine body as the human archetype, with the feminine treated as a kind of sub-variant. Aristotle infamously suggested that women were “misbegotten males,” implying that femininity, in his understanding, was a kind of corruption of the normative masculine model.

Beauvoir thinks that women have also, for the most part, internalized this same paradigm, accepting their status as “second,” the supplementary sex. Whether or not they would judge women to be inferior, both sexes default to this same pattern of treating manliness as the norm against which both male and female behavior is ultimately measured. Beauvoir notes, for instance, the trend among psychoanalysts of classifying many youthful behaviors, when seen in girls, as imitation of boys. “When a little girl climbs trees it is, according to Adler, just to show her equality with the boys; it does not occur to him that she likes to climb trees.” A man is simply a human being; a woman is a female human being.

I think that this claim, as a big-picture generalization, is hard to dispute. A drawn-out discussion of second-sexhood might consider the cultural significance of the goddess Athena, Socrates’ Diotima, Joan of Arc, Marianne, and Boethius’ conversation with Lady Philosophy. But taking the sweep of human history at a glance, these do seem like rule-proving exceptions. It does not surprise anyone that da Vinci illustrated the proportions of the human body with a Vitruvian Man; a Vitruvian Woman would have thrown us into a gender conversation. Across most of history, women have had fewer political and civil rights than men, usually enjoying only attenuated forms of citizenship, mediated by their male relations. Man is the citizen class; woman is the adjunct class.

One of my sons recently illustrated Beauvoir’s point in a humorous way when he asked me why a book he had found on the shelf (All of a Kind Family) was dominated by girl characters. I laughed and rattled off a lengthy list of male-dominated stories we’d read together, which had occasioned no comment about gender imbalances. I won’t detail the conversation that followed, except to say that it was enjoyable and interesting to hear his thoughts. One needn’t have any animosity at all against girls to become accustomed to expecting that men, not women, will normally occupy the foreground, in public life and even in fictional stories.

How did woman become the second sex?

Broadly speaking, there are three kinds of answers that could be considered here. Woman could just be inferior to man. Or, it could be that the sexes are “different but equal” in such a way that it is both fitting and beneficial for them to occupy different spheres. (Woman, in that case, would typically be placed in a more restricted, though also more protected, social space.) Finally, woman might be systematically disadvantaged in such a way that it is hard for her to assert herself as man’s equal.

Beauvoir lands pretty squarely on this third option, and while she acknowledges that size and physical strength may be relevant, she thinks fecundity is the main causal factor.

Women, Beauvoir thinks, are perfectly capable of high and rarified achievements, on a level with those of men. They’re unlikely to win the tractor pull, but they too can find great satisfaction in building, exploring, learning, discovering, and exercising the creative powers. They’ve enjoyed far fewer opportunities to do these things, primarily because childbearing is so onerous, both for them and for society at large.

Maternity is wrapped in its own gauzy mythology, but even now, and even among people who see themselves as enthusiastically pro-life, it’s still difficult to convert maternal achievements into any currency that’s accepted outside the kitchen.

This is an important factor that we can easily miss, living in an age of falling birth rates. It’s just not the case that, prior to the modern era, childbearing was consistently viewed as a source of joy and blessing. Most societies do, of course, wish to perpetuate themselves, but a young woman’s natural capacity for childbearing is in a sense “excessive”; the free gratification of sexual appetite will lead to more babies than most societies need, want, or have the ready capacity to support. Sexual discipline is one solution (albeit unpleasant to some people), but this is also why exposure has been practiced in so many pre-modern societies. And, in Beauvoir’s view, it explains why women have generally held such a weak hand in social, political, and economic terms. Biology itself has assigned them a social contribution that is necessary but not highly valued, and because the trials women undergo along the way (especially pregnancy and childbirth) are only minimally voluntary, they aren’t regarded as meritorious on anything like the same level as men’s. To survive, women frequently have to settle for what they can get. That might mean “purchasing” needed security and support at the cost of fewer liberties, less social respect, and a willingness to accept the more tedious and unglamorous jobs. Very few women historically have enjoyed a liberal arts education or the leisure they would need to write novels or paint frescoes.

I think this argument leaves out some crucial things; nevertheless, in the big picture, it’s fairly plausible. It explains rather well why women’s education has indeed precipitated a dramatic upswing in women’s rarified achievements. No one is amazed anymore to see women writing excellent novels or doing valuable scientific research. Beyond that, I find that even today, and even among people who view childbearing very positively (such as religious conservatives), it is often a struggle to persuade people to see childbearing in a way requisite to other roles and contributions, as something meritorious and honorable. Traditionalists love to stress that maternity will make women happy, but euphoric portrayals of domestic bliss are still the preferred pro-natal pitch. Maternity is wrapped in its own gauzy mythology, but even now, and even among people who see themselves as enthusiastically pro-life, it’s still difficult to convert maternal achievements into any currency that’s accepted outside the kitchen.

As an instructive illustration, I reflect back on an argument I once had with a conservative man about policing. It had something to do with reasonable expectations for cops in hazardous situations, and he was of the view that I, an armchair intellectual, couldn’t possibly understand what it would really be like to put my very self on the line for the sake of others. When I pointed out that I had given birth four times in the previous six years, he just seemed confused. A man who bleeds for other people is a hero, but when women do it, that’s easily shrugged off as just the natural order of things.

Having said all of that, I must also note that it is perfectly possible for healthy forms of gender complementarity to develop alongside social practices that unfairly disadvantage women. My second and third explanations (in the first paragraph of this section) aren’t really mutually exclusive. Women might, as a group, be better suited overall to domestic roles, and it could be that many or most of us are happier in a somewhat protected social space. It could be that men (in the aggregate) have a somewhat stronger drive to build and explore, and women (in general) a greater appreciation of the benefits of warm, supportive, human-relationship-oriented spheres. I find that fairly plausible in fact, provided plenty of space is left for individual variation. But that’s also perfectly compatible with women being significantly disadvantaged in ways that do matter, undercutting both their human potential and their personal thriving. Beauvoir’s relentless focus on equality and disadvantage could reveal certain truths about the sexes while obscuring others. This leads to the next question.

Is it a misfortune to belong to the second sex?

Beauvoir certainly thinks so. As Melonic notes, her account of the life cycle of woman is bristling with indignation. Everyone seems out to get her; her argument with Levinas (discussed by Melonic) further reveals the depths of her victim complex. Beauvoir is anxious to liberate women from the curse of maternity, through the ready availability of contraceptives and abortion on demand, but also through pie-in-sky communist labor-sharing schemes.

She is particularly anxious about women’s opportunities for transcendence, which she as an existentialist understands as a kind of autonomy or self-mastery. She wants to pursue happiness, not wait for a man to gift it to her. Returning to the “second sex” problem, Beauvoir believes that woman’s secondary status has been reinforced by a pervasive tendency to “other” her. Because man is understood to be the normative sex, woman is cast as his complement, ostensibly embodying whatever qualities would best enable him to thrive. She becomes the fertile and nurturing earth to his sky, the “angel” of his house, the wind beneath his wings, or whatever seems most fitting given the tenor of a particular age. His wishes, interests, and potentialities are extremely important, as the normative sex; her needs need not be examined in great detail because we understand from the start that she is the support staff. She exists to be secondary.

I think Beauvoir’s political and policy views are bonkers, not to mention grossly unethical. There is, as Melonic says, a profound narcissism to her perspective that here becomes glaringly obvious. Is everything about sex? Must we endure any and every distortion of the natural order, for the sake of women’s autonomy? As we are discovering in our own time, that impulse can be taken almost to infinity, and it’s a game that everyone can play. People can, after all, be disadvantaged in all sorts of ways, and for all sorts of reasons. Even being the first sex can be uniquely burdensome in certain ways.

Beauvoir’s determination to see the world through the lens of disadvantage keeps her from appreciating many of the good and rewarding elements of both womanhood and maternity. She doesn’t reflect sufficiently on the ways that men can actually love women, and sincerely want them to thrive. She gives too little attention to the way that maternity can be embraced as part of the transcendence she desires. (This can even be true of physical childbearing itself. It’s essentially the explanation I used to give to people who were perplexed by my affinity for natural childbirth. “I just prefer,” I used to say, “that giving birth be something I do, not something that happens to me.” This seems like something Beauvoir would have appreciated, but unfortunately, she chose to put the balance of her energies into promoting abortion, not birth.)

The Second Sex shows how extremely imprudent it is to jump from a diagnosis of disadvantage to an uncompromising demand for redress. Life is often unfair. Sometimes there are reasonable and prudent ways of mitigating that, but often we just have to play the hand we’ve been dealt as well as we can, ideally with grace and dignity. Refusing to accept this truth will leave you miserable and bitter, and may even persuade you to kill your own children.

We have also seen, time and again, that a zero-tolerance determination to correct for historical injustice can lead people to reject almost the whole of Western history as sexist, racist, homophobic, and overall too offensive to be tolerated. That slash-and-burn approach to history and culture leaves everyone impoverished. Maybe Aristotle did have female relatives (his daughter Pythias, say) whose philosophical potential was inadequately developed, and if so, that’s a shame. But his work is still pretty amazing, so let’s not cut off our noses to spite our faces. I consider Western Civilization my rightful inheritance as much as any man’s, and I’d rather claim it than obliterate it out of spite.

For all that, I still find Beauvoir’s concerns about the “othering” of women to be on-point and compelling, at least in particular times and places. They may be more relevant than ever today, when the progressive left’s determination to deny the significance of sex leads many on the other side to demand robust and clearly defined gender roles. That gender-maximalist impulse generally works out badly for women, as men are encouraged to aspire to every kind of rational excellence, while women are expected to rejoice in airy purple prose about the joys of homemaking. The problem is evident in quite a number of recent books from the right, and so closely tracks Beauvoir’s analysis that I personally refer to it simply as “the second sex problem.” There are still people out there (growing numbers, it would seem) who want man to be the normative, excellence-seeking sex, while woman joyfully takes up her appointed post as his support staff.

In my view, that kind of thinking can only make it harder for young men and women to find happiness together. If, in diagnosing this problem, I find myself allied with an abortion-promoting communist, then all I can say is that strange times make for strange bedfellows.