Pieter Bruegel’s "Hunters in the Snow" is one of the masterpieces of western art.

The Next Renaissance

Legend has it that Giotto di Bondone, the man who brought painting back to life, started out in the late 1200s as a simple farm boy. When Giotto was a lad, we’re told, his father made him deputy shepherd on the family property. This involved long hours of downtime, which Giotto would while away by sketching whatever he saw, wherever he could—on rocks, in the dirt, or in the sand. One day Cimabue, Florence’s greatest living painter, happened upon Giotto while out on business and found him drawing a sheep.

Giorgio Vasari, whose Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects is modernity’s first true art history, probably read about Giotto’s humble origins in the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Commentaries. Vasari’s own account of the fateful meeting crackles with potential energy: there was the boy Giotto, “with no instruction from anyone else except from the promptings of nature,” doodling upon the face of the earth with a hand that would revolutionize painting. What Cimabue saw made him “stop short in the utmost amazement”—no mean feat considering that Cimabue, i.e., “the bull-headed,” was known more for his talent than his critical generosity.

Cimabue had begun already to slip the surly bonds of what Vasari called the maniera greca, the severe style of mosaic and painting whose eerie rows of looming saints and angels still haunt the interiors of Byzantine churches. Giotto surpassed even Cimabue and “became such an imitator of nature that he cast out that rude Greek manner for good.”

Between these two men there ignited a fire of invention that melted away centuries of ruin. They recovered a kind of greatness that had not been seen, says Vasari, since the days of ancient Greek painting and sculpture. Here was a living art of rippling muscles and fabrics, of pregnant glances and delicate gestures. Vasari called it a rinascita, a “rebirth” of antiquity’s best techniques—the beginning of what would be known thereafter as “the Renaissance.”

The Actually Guys

It’s such a breathtaking story that one hesitates to spoil it with facts. But documentary sources have made it look increasingly likely that Giotto was not really raised on a farm at all—to the dismay of locals in Vicchio di Mugello, the remote Tuscan village where Giotto was supposed to have grown up. In fact he may have been the son of a metalworker, raised in Florence and instructed by the artisans there, not by the sylvan Muses of the countryside. Perhaps not even by Cimabue, for that matter, although it is still quite possible that the older master mentored the young prodigy.

Vasari, as was his wont, grafted ancient anecdotes and contemporary urban legends onto real events. The result is not so much a factual account of Giotto’s life as an allegory about his place in history. We expect a modern biography to debunk myths, not indulge in them. But in the ancient world, a vita (“life”) of a great man was more like a literary portrait, freely blending fiction with fact. Vasari, following chroniclers of artistic achievement from the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial periods like Pliny the Elder and Diodorus Siculus, told his tall tales to get big points across.

What Vasari is conveying with all his stories is the miracle of ancient truths given new life.

Time has chipped away at Vasari’s anecdotes and undermined his sweeping critical assessments. For one thing, the maniera greca, that supposedly clumsy medieval style which serves as a foil to Vasari’s brilliantly humane Renaissance, has always had formidable defenders. And indeed Cimabue’s own last great work, a soaring mosaic of Christ enthroned in the apse of Pisa Cathedral, is as impressive an example as any of Byzantine majesty. Tuscan painters moved beyond this luminous style not because they disdained it, but because they had reached the furthest limits of what it could achieve.

Besides these matters of taste, history has dealt a series of blows to Vasari’s credibility on matters of fact. One particularly notable revision has to do with the “Rucellai Madonna,” a painting that for Vasari marks out Cimabue as the harbinger of future glories. Vasari tells a moving story of how this 14-foot-tall masterwork was paraded with ecstatic fanfare from Cimabue’s house to the church it would adorn, “because until that moment nothing better had been seen.”

The Madonna is indeed an unqualified triumph—but apparently not Cimabue’s. In 1889 the Austrian art historian Franz Wickhoff argued that the painting was really the work of Sienese painter Duccio di Buoninsegna. Wickhoff’s arguments are now almost universally accepted, and even if they weren’t, there would still be plenty of holes to poke in Vasari’s story. Modern skepticism has not been kind to grand narratives, however satisfying: this is the age of the “actually guy,” whose exceptions, corrections, and counterexamples interrupt even the most exhilarating morality tales.

And yet, for all that—for all Vasari’s overgeneralization and imprecision, for all his fanciful storytelling and factual errors—still there is something supremely true about his overarching tale, something the actually guys can neither refute nor minimize. There is a reason we still use Vasari’s central idea—Renaissance, rinascita, rebirth—to describe the 300 years of cultural transformation he surveyed. What Vasari is conveying with all his stories is the miracle of ancient truths given new life.

You can feel it still in Florence if you stand before the Rucellai Madonna. The painting now towers imposingly on a wall in the Uffizi Galleries, which Vasari himself designed at the prompting of Cosimo I de’ Medici. As a matter of style, if not of devotion, what really commands attention in the painting is the angels. As art historian Hayden Maginnis writes in his Painting in the Age of Giotto, “the six angels seem to bear the Virgin’s throne, complete with dais, toward us…. This conceit was so revolutionary that it required the invention of equally revolutionary forms.” The angels of the Rucellai Madonna are lifting heaven bodily down to earth, their knees and hands straining powerfully to break the Virgin out of her otherworldly Byzantine background. She no longer floats in a distant sea of gold: she lands here, weighty and alive. It is an incarnation.

True enough that what went before the Rucellai was not as “rough and crude” as Vasari makes it out to be. But here in the painting of the 1200s is something undeniably and magnificently new, something that would clothe heaven’s formerly alien majesty in almost tangible human flesh. So maybe it wasn’t Giotto who first broke that ground—maybe Duccio deserves credit for cracking open the door to what came next. But someone did it. And the achievement is worthy of all the grand pageantry that Vasari envisions in honor of the Rucellai Madonna. No matter what Vasari got wrong, he was right about that.

Life Cycle

Cardinal John Henry Newman, in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, wrote that a new philosophical movement is like a stream bubbling up from its source in the earth: “It necessarily rises out of an existing state of things, and for a time savours of the soil. Its vital element needs disengaging from what is foreign and temporary.” The same might be said of Renaissance art, which had a long way to travel from Giotto and Duccio before it achieved its full potential.

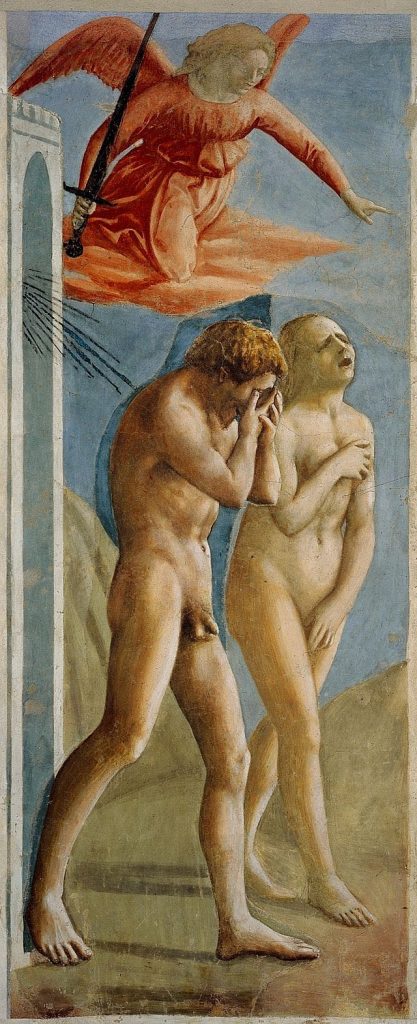

Vasari describes this gradual development in three stages: birth, development, and perfection. After that original moment in the 1200s, meticulous technicians like Paolo Uccello labored to perfect the visual mathematics of depth and perspective, while students of gesture and expression like Masaccio suffused the new landscape with human passion (the raw anguish of his Adam and Eve is still harrowing as they stumble perpetually forth from Eden in the frescoes at Santa Maria del Carmine Church). This period of refinement ultimately enabled the consummation of the new art, which Vasari identifies in the breathing marble of Michelangelo and the stately tableaux of Raphael.

Here, too, Vasari is telling a true story of how individual genius arises out of developments in history, then shapes the course of that history in turn. Collaboration and invention, patronage and political circumstance all interlock in a delicate machinery—and none but God can tell in advance how the whole thing will be orchestrated. “The nature of this art, like those of other arts and like the human body, has its birth and its growth, its old age and its death,” writes Vasari: centuries of grandeur and discovery have a natural lifespan because they are creations, shaped by the same artist who sculpted the human form out of dust.

A renaissance does not happen by accident, but neither is it in our control. God plants and waters what seeds he pleases.

You can see the record of this process when you visit the great plazas and cities of Tuscany. Florence’s cathedral, most famous for the dome engineered in 1436 by Filippo Brunelleschi, was begun at the tail end of architecture’s Gothic period, meaning that the building itself straddles almost the whole lifespan of Vasari’s Renaissance. In one of the friezes that adorn the exterior, a Solemn Christ bathed in Byzantine gold finds himself flanked by swooping angels whose joyous posture comes right out of Masaccio. It is like looking at a whole process of evolution locked into stone, the sedimentary layers bearing witness to Vasari’s three stages—birth, development, and at last perfection.

Something like a renaissance does not happen by accident, but neither is it in our control. God plants and waters what seeds he pleases. Maybe there is some comfort in this for our own day, when so much of our culture feels exhausted and sterile. The album of the summer has been called “RENAISSANCE,” but the capital letters protest too much: we are still suffering through remake after reboot after prequel at the movies and on TV; self-indulgent scribbles or gestures of sophisticated inanity in art galleries; and a stultifying code of political and demographic piety in storytelling of every kind. On streaming services and at the Met, it’s hard not to feel like we’re in a bit of a trough.

Maybe we are. For one of Vasari’s most trenchant and melancholy insights is this: if greatness in art has a kind of organic life, then like all living things, it must pass away. Just as it is impossible to look honestly at Florentine painting and not see something majestic taking shape in the 13th and 14th centuries, so it is hard to watch the trajectory of 20th-century cultural output in the West without a sense of loss.

Yet Vasari had just such a loss in mind when he wrote: “I hope that if…through the negligence of men, or the spitefulness of time, or at last through the decree of Heaven, which apparently does not consent that the things of earth should exist for a long time in the same form, art should fall again into the same chaos of ruin, that these efforts of mine…should keep her alive, or at least encourage the most exalted minds.” It gives one a certain thrill of recognition to realize that we are the future generation to whom Vasari was writing, living through just such a dry spell as he knew would come.

On my most optimistic days, I hope I see the stirrings of another rebirth already. I have argued in this publication that some of the best video games constitute a rebirth of the heroic spirit in visual and narrative art. But there are other signs of life, too: Passage Press is awarding prizes and publication to the best literature and visual art without regard for woke niceties. At canonic.xyz you can find a growing library of exciting new fiction and non-fiction published on Bitcoin. The digital age, for all its discontents, is unleashing a new wave of creative energy.

Probably only retrospect will tell whether these early achievements have met with the right political and historical circumstances to make for a new renaissance. Yet it seems to me Vasari is saying, with special urgency for this moment, that renaissance will come. The last one—that wild effusion of joy that lit up the towers and cathedrals of Europe, clothing the dry bones of antiquity with sinew and pumping Christian blood into the veins of the old gods—was bound to end sometime. But even if we are living today among the ruins of something greater than ourselves, the spirit which once animated those ruins has not abandoned us. It blows where it will, and when it blows it gives life to things long dead. Our job is to work, and to wait.