Under a flashing neon sign proclaiming “human unity,” contemporary Europeans would have humanity arrest all intellectual or spiritual movement.

A New Christian Progressivism

Many Americans are rightly chagrined by the direction of their country. The political, moral, and economic grotesqueries long favored by our ruling classes are now bearing particularly poisonous fruit—a story too familiar to recount.

One response to those elite preferences, and the policies that have grown from them, has come from a handful of theological-political thinkers known as “integralists.” Integralism is very much a moving target, and no definition of it is likely to satisfy all. The movement consists largely of young men in a hurry, some of whom embrace the label, while others are merely fellow travelers. It’s nevertheless fair to say that integralists and their acolytes share some major sources of disquiet about the American regime. Ironically—or perhaps not so ironically—the problems they identify and the solutions they propose have much in common with Christian progressivism of the early twentieth century.

Integralism, American style—like the progressivism that went before it—comes to sight as a critique of the American constitutional order, which it sees as the apotheosis of Lockean liberalism. And it is this Lockean liberalism, or so the critique goes, that is the genesis of many if not all bad things in our public life. This is a point made repeatedly by political theorist Patrick Deneen, whose 2018 book Why Liberalism Failed has proved peculiarly popular among integralists. According to this account, a republic of individual natural rights cannot support a conception of the good life, or a politics of the common good. Integralists see the US Constitution as the embodiment of a set of modern principles that sought to overturn ancient teachings and shape a distinctly different human being, steeped in rights, but freed from obligations.

For the integralists, liberal politics, economics, education, and science are each oriented to liberating the self from the constraints of custom, culture, and nature. In this sense, the project of early-modern “classical liberalism” and late-modern “progressive liberalism” is the same. Liberalism as a whole amounts to a politics of the self, a comprehensive “anti-culture,” in the words of Deneen.

The integralist goal is to liberate us from this modern project. The path to liberation is through a powerful state—one that adheres to Christian, and especially Catholic, faith and social teaching. Integralists can find no alliance with constitutional originalists, both because they think the Constitution is tainted by the original sin of liberalism, but also—somewhat inconsistently—that the Constitution is open-textured enough to allow strong men, within the executive branch and the administrative state, to pursue a politics of the so-called “common good.”

The urtext of contemporary integralism is a short essay by Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule, published in The Atlantic on March 31, 2020. It is a piece that has not aged well.

Vermeule argues that “this time of global pandemic” calls for a concentration of power in the name of the common good. Government “must have ample power to cope with large-scale crises of public health and well-being—reading health in many senses, not only literal and physical but also metaphorical and social.” Not wanting to let a good health crisis go to waste, he maintains the “procedural rules” of the liberal legal order may now be dispensed with. Instead, “officials” must read “substantive moral principles” into “the majestic generalities and ambiguities of the written Constitution.”

Channeling his inner Max Weber, Vermeule says such principles would include “respect for the authority of rule and rulers,” and respect for “hierarchies.” Practically speaking, this means a “powerful presidency ruling over a powerful bureaucracy.” Forced vaccinations are only the beginning. The moral experts would also enjoy free reign to deal with “climate change,” among many other things. No “selfish” claims to “private rights” can be allowed to stand in their way. When the fullness of time came, God sent the administrative state.

Vermeule claims he can be “methodologically Dworkinian” in his “moral readings” of the Constitution, while not sharing Dworkin’s liberal commitments. He implies there is little risk in this—because all he needs are the right rulers with the right morality. Things get even better insofar as common-good constitutionalism “is not tethered to particular written instruments of civil law or the will of the legislators who created them.” The goal is not to “minimize the abuse of power,” but simply to ensure that power is used for good. The law must be seen as “parental,” regardless of what its “subjects” might think. In fact, “subjects will come to thank the ruler whose legal strictures, possibly experienced at first as coercive, encourage subjects to form more authentic desires.”

That such an intellectually embarrassing trainwreck of an argument would launch a movement says much about its followers.

To lean into Veremeule’s public health example, a skeptic might ask if anyone would wish to live through another public health crisis wherein only the judgment of common-good rulers stood between them and the clutches of the national state—without the legal and political pushback of local and state institutions. Even given how attenuated that pushback was from 2020–22, it was still better than nothing. Some states and localities were far more tolerable to live in than others. The least tolerable were those most directly under the thumb of rulers who preached precisely about the common good—and our obligations as subjects, rather than our rights as citizens.

In short, there is still a useful place for formal, legal limitations on power—such as the federal principle. Human flourishing is not likely to be furthered by the unchecked rule of moralists relying on some not-quite-worked-out version of subsidiarity. To quote Kid Rock—a greater philosopher and poet of the American regime than even the best of the integralists: “Wear your mask, take your pill, now a whole generation … is mentally ill.”

It should be noted that common-good constitutionalism renders written constitutionalism nugatory, just as progressive living constitutionalism did before it. There is, after all, no point in having a written constitution if it’s simply an empty vessel into which the concoctions of the ruling classes may be poured: if its terms are malleable enough to support the non-consensual rule of elites.

It’s useful to compare in more detail the integralists to the Christian progressives—both Catholic and Protestant—of a century or so ago. They too mobilized intellectually and politically around the purported inadequacies and injustices of the framers’ Constitution and the modern economic order. They did so with a fervor for, and faith in, non-consensual expertise, which they thought could remedy injustice. The intensity of that fervor and faith can be traced to the religious impulse.

Throughout the Progressive Era, religious language was common at political gatherings, including even national conventions. The Progressive Party convention of 1912 adopted “Onward, Christian Soldiers” as its anthem, and Teddy Roosevelt compared the upcoming campaign to Armageddon. The Bull Moosers insisted that they would do “battle for the Lord.” Furthermore, the fervor of Christian progressivism was unlike that of prior American religious awakenings. Instead of concentrating on individual moral failings and the need for individual reformation, Christian progressives, like integralists now, concentrated their gaze much more on matters of social and economic justice. By the first decades of the twentieth century, both Protestant social gospelers and Catholic reformers were vigorously attempting to shift the center of gravity of mainline Christianity toward applying Christian ethics in the here and now. The real presence of Christ came to take on new significance.

Progressive theologians began to point to what they claimed was the essentially social and political nature of the Christian enterprise. For example, Fr. John Ryan, in his 1906 book A Living Wage, sought human solidarity and heavenly justice through economic policy. And in this quest, he worked to turn Catholicism—as the Social Gospel had turned Protestantism—against the American system of constitutionally limited government, private property, and capitalism, all in the quest for a more rational scientific state that would support something like the Kingdom of God on earth.

Fr. Ryan was no particular friend to self-government, and insisted that monarchic or aristocratic forms could claim legitimacy, depending on circumstances. The state should ideally recognize the one true religion, i.e., that professed by the Catholic Church, and prevent the introduction of new forms. He allowed that Catholic states wherein other denominations were already established should generally tolerate them as a matter of prudence. But no rights are absolute in the sense of being ends in themselves—including freedom of conscience. All aspects of the state should be understood as the means to human welfare. And so, Fr. Ryan leaves to the good judgment of Christian rulers vast amounts of discretion as to what constitutes public welfare, even in matters of conscience.

Progressive theologians came to deemphasize the idea of helping oneself as the key both to personal prosperity and to becoming functioning moral agents in a stable society. They also took little account of the problem of scarcity, or that government economic mandates are often exclusionary rather than inclusionary. For example, they favor those who are already employed, rather than those who seek employment. Administrative rules exclude, monopolize, and stratify.

Concentrating as they do on social sin, they are excused—like their forebears—by two facts: integralists do not understand politics, and they do not understand Christianity.

The roots of the modern administrative state—and confidence in the power of elites—thus run deep in the soil of Christian progressivism, as contemporary integralists now seek to use that state for their purposes. To the extent a secular millenarianism is evident in the rhetoric of both contemporary liberalism and Christian integralism, it can trace its origins to the rather insistent piety of the early progressive religious thinkers.

Christian progressives joined forces with economists like Richard Ely and political scientists like Woodrow Wilson against what they claimed were the new economic and social realities that had been fully unleashed by the modern industrial age. Christian progressive thinkers pressed for an expansion of state power, and especially national state power, at the expense of constitutional limits. And in the case of the theologians, it was also at the expense of the sacred, even as the essential revelations and rituals of Christianity were still important to them. Theirs was a natural law, or theological diktat, that helped ensure government’s protean expansion, as it reduced Christian faith to a set of economic and political demands.

Compared to the early Christian progressives, the integralists’ vision is even more comprehensive, and less defined—economic statism being only one aspect of it.

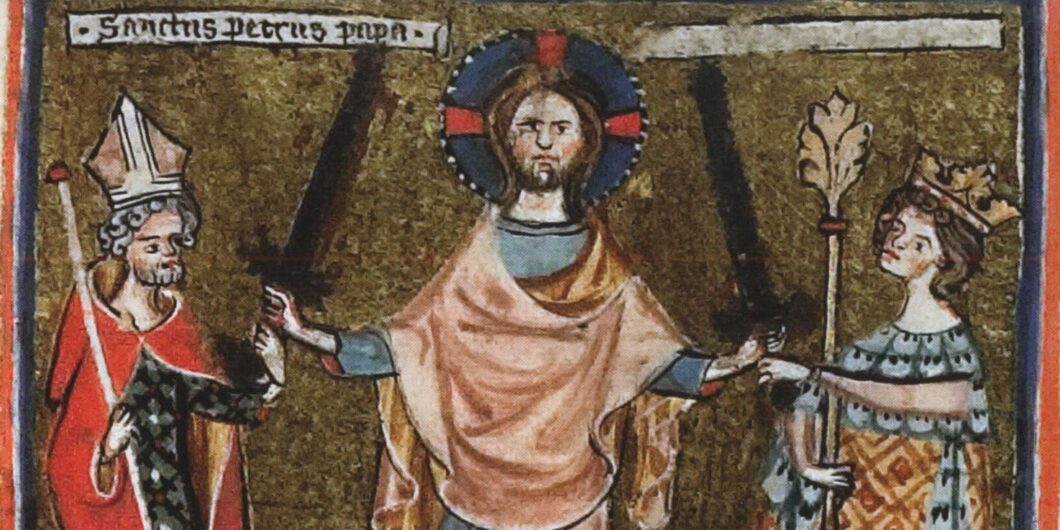

Almost no major facet of the modern world escapes the withering gaze of the integralists. Unsurprisingly, some of them are Catholic monarchists, and even express a desire to return to the politics of the medieval world, while others are more circumspect. But they are all men without a country. A strong vein of authoritarianism—evidenced perhaps by their impatience with critics who seek clarity—runs through integralism.

Integralism is often identified as a species of political conservatism, although it is hard to know in what sense. In fact, it is very radical in its rejection of both America and the Enlightenment in toto. It goes too far in reducing modern political thought to the false anthropology of self-creation. Reducing liberty to the complete freedom to pursue one’s desires is unfair even to the philosophic originators of modern liberalism and, a fortiori, to the framers of the American Constitution, who were morally grounded statesmen, not philosophers. The framers understood the consenting individual to exist in an obviously political sense, i.e., that no man is so naturally superior to another to be entitled to rule the other without his consent. This rests not on a dangerous voluntarism or radical individualism, but on a recognition of moral, political, and theological reality. Certainly none of the framers believed in “unfettered and autonomous choice.” Instead, they believed, and acted as if they believed, in self-government, which presupposes the taming of the passions through custom and law. A century after the ratification of the Constitution, it was American progressives, far from being of one mind with the framers, who wrote voluminously against what they saw as the framers’ anachronistic, natural-law thinking—and against the Constitution that was its product.

Without question, modern liberalism is a target-rich environment. But so is the integralists’ alternative. Ultimately, it is their human anthropology that is false, and heretical—borrowing from, yet at the same time masking or distorting, Christian doctrine, including its recognition of what stands in the way of God’s will being done on earth as it is in heaven. Not all sin is social; much less is it Lockean, or particularly American. After all, the impulse toward autonomy and mastery long predate modern political philosophy: “So, when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree desirable to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate.” To borrow from Dostoyevsky, the fire is in the minds of men, not in the roofs of the buildings.

Modernity, and especially its American variant, did not seek to unleash the dangerous passions that constitute the soul, but to tame them through new modes and orders. Integralists would unleash them again, in accordance with their gods. They could pause to reflect a little more on the American Enlightenment thinker par excellence, James Madison: “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

Limitations on government are unnecessary only if that fixed conception of human nature—that men are but men, as they were in the beginning—is rejected. And for this rejection to appear plausible, both reason and revelation must be dramatically reconfigured. We certainly don’t get to the common good merely by exhorting a politics of the common good, or engaging in an unending critique of market liberalism. After all, meddling in the affairs of others—in the name of pursuing social justice, or the common good, or doing God’s work—nowadays tends to be undertaken by philosophical, theological, and political incompetents, or worse. But thus has it always been. Theologically speaking, we are embodied individuals. Any decent political order must take account of this. The individual, and the rights he has by nature, cannot be sacrificed on the altar of an ill-defined common good. The question is always, how might we best prevent this?

But perhaps the greatest threat that integralism poses is to Christianity itself, which ultimately works through love—not force, or politics. It can only flourish, as itself, when conscience is free to choose it. In the words of Milton Friedman, we really are (at a level deeper than he probably imagined), “free to choose.” God made us so. No confession of faith in the American context is possible, or desirable. Over such a thing, there will be blood. The integralist vision seems to require conflict. The integralists, like the early Christian progressives, do not evince much concern that the church will not purify political pursuits, but be corrupted by them, and ultimately destroyed by them.

But in concentrating as they do on social sin, they are excused—like their forebears—by two facts: they do not understand politics, and they do not understand Christianity.

This essay is based on a lecture delivered at the spring 2023 meeting of The Philadelphia Society, of which the author is vice-president. The views expressed are his own.