Activists often claim a kind of sacred wisdom about transgender issues. But in the UK, at least, that's now up for debate.

Acta Non Verba

Champion Australian cricketer Keith Miller was once asked how he coped with pressure as a player, especially given his stature as the country’s preeminent “allrounder”—equally capable with both bat and ball—and membership of a Test team later known as “The Invincibles.”

Storied BBC interviewer Michael Parkinson was Miller’s interlocutor, and the cricketer’s response became legendary. “I’ll tell you what pressure is. Pressure is a Messerschmitt up your arse. Playing cricket is not.”

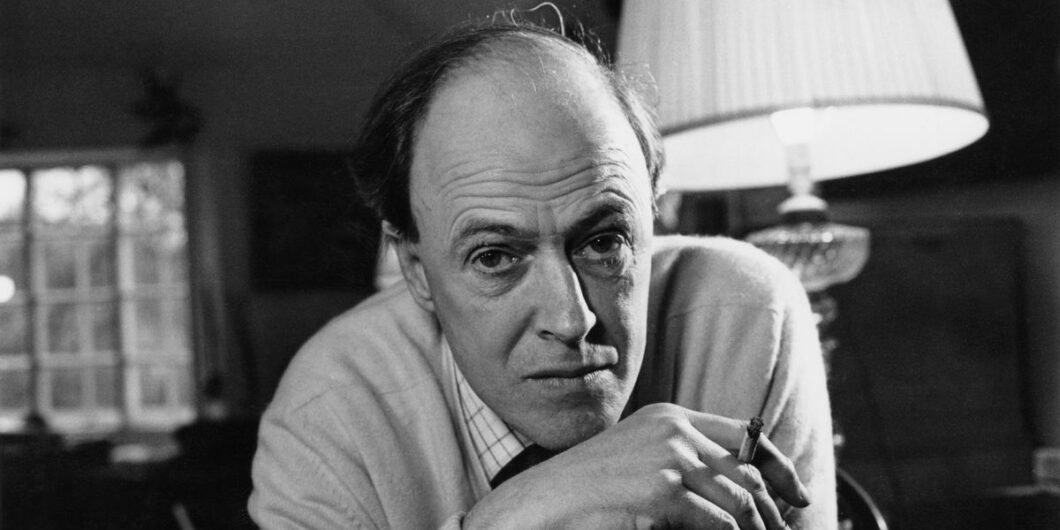

It’s a sentiment with which fellow RAF fighter pilot Roald Dahl would have agreed, given Dahl’s status as a bona fide air ace who fought against a numerically superior Luftwaffe in April 1941’s doomed dogfight over Athens. Of 12 RAF 80 Squadron Hurricanes involved, five were shot down and four of their pilots were killed. Among the dead was Pat Pattle, the highest-scoring British Commonwealth ace of World War II.

Of course, Roald Dahl has been in the news of late for other reasons.

In February, his publisher announced it’d hired a team of “sensitivity readers” to bowdlerise his classic children’s novels, removing words like “fat” and “flabby” while promoting female characters to roles they were unlikely to have held when the books were written. There was then an enormous public backlash, including people from Sir Salman Rushdie to Camilla, Queen Consort, eventually dragging in a significant chunk of the Great British Public. Dahl is behind only J. K. Rowling in these Islands for literary popularity and behind Rowling and America’s R. L. Stine globally.

Puffin (Penguin’s children’s imprint) beat a hasty retreat, promising a “classic” edition that would leave Dahl’s words unmolested. One suspects, however, that the bowdlerised version will be automatically made available to primary schools, which means librarians need to be alert that they aren’t sold a pig-in-a-poke.

After a great deal of to-and-fro, the net effect of the Dahl imbroglio was to bring to global attention the extent to which children’s literature—writing, publishing, representation—has been afflicted with wokery. Famed children’s authors like Rowling haven’t just been buried neck-deep in the poisonous transgender debate. Entire books have been pulled pre-publication based on tiny snippets taken out of context and propagated around the internet; there is widespread author no- and de-platforming; electronic editions have been surreptitiously altered (something that Amazon, for example, can do remotely).

In the worst case, it emerged that Dahl’s competitor for global kidlit author Number Two, Stine, had his publisher bowdlerise the e-book versions of his Goosebumps series behind his back. Stine was unaware of what had been done to his work for some five years, blithely assuring fans who told him about it on Twitter that “I’ve never changed a word in Goosebumps.”

Stine’s situation was horrendous to me for personal reasons, even though he wasn’t an author I read as a child. He first became popular in the 1990s, after I’d left school—indeed, at the point where I was establishing a literary career. My disquiet came about not only because he wasn’t told and proceeded to embarrass himself in public. It was also because his publisher is Scholastic, which (as Ashton Scholastic) holds a sacred place in the memories of many Generation-X Australian readers.

While I remember my parents buying the likes of Dahl or Australian children’s writers Mem Fox and Norman Lindsay from local brick-and-mortar bookshops, Ashton Scholastic had a contract with multiple Australian education departments to supply books at reduced rates to students in primary schools. Many pupils paid for them with pocket money. Every couple of months, the books (to which, in my case, I’d applied my hard-earned paper-run profits) would arrive and teaching staff would hand them out to eager young readers at morning roll call.

Scholastic’s treatment of Stine felt like a betrayal of my younger self.

As various people pointed out in the wake of the Dahl imbroglio, “sensitivity readers” and publishing companies who hired them don’t seem to understand what children like in books, while sensitivity reading itself has entirely confected criteria. Stine proudly states in his Twitter biography that he’s out “to terrify kids.” Dahl’s works are laced with macabre humour, grotesque characters, and black magic. Remove the villainy and much of what young people love about his writing evaporates.

This anarchic sensibility appears among other popular children’s authors, too. Australia’s Lindsay wrote The Magic Pudding—famously, children’s author Philip Pullman’s favourite book—because he thought children preferred food and fighting to fairies. Rowling’s Hogwarts, meanwhile, never loses its menace, not even when Harry, Hermione, and Ron have mastered enough magic to cope with an education there.

The reason children’s literature is a site of conflict in this way has deeper roots than wokery, however. For centuries, even millennia, there was a widespread belief literature that sets a poor moral example is corrupting. This, of course, is the reason Plato wanted to exile poets and playwrights from his utopian Republic.

Nonetheless, in more recent decades, what sometimes goes by the name “media effects theory”—Plato’s claim that people’s behaviour is influenced by the media they consume—has been comprehensively falsified in adults. Even in totalitarian states, propaganda turns out to be surprisingly ineffective, with the authorities depending to a much greater degree on policy successes elsewhere (think Nazi Germany’s full employment) and scarifying secret police (Gestapo, NKVD, Stasi, KGB).

People over thirty-five will no doubt recall repeated claims that video nasties, single-player games, and pornography produced everything from school shooters to sex offenders. Not only were these allegations not true, but the evidence base in the case of porn was weak to the point of non-existence. This means, in recent years, a new and very different contention has emerged. To wit, that watching too much porn causes erectile dysfunction (a condition incompatible with the perpetration of most sex offences). Thing is, that’s not true either, as statistician Stuart Ritchie points out in this amusing evidence review.

It should be possible—for both children and adults—to draw a legible distinction between Roald Dahl’s words and actions.

Ritchie also sounds an important warning. Many people—people who often aren’t particularly numerate—want to recruit maths and data to their cause:

Incidentally, it’s interesting that a major anti-porn argument nowadays is that it causes erectile dysfunction, because I distinctly remember a time where the focus was that porn turns men into enraged, barbaric sex-offenders. The charitable interpretation is that it might have opposite effects on different people—but I must say I haven’t seen any decent evidence for that, either.

I wonder if this is similar to a case I made elsewhere a while back about violent video games: that people are mistaking their aesthetic or moral disgust reactions about pornography—which are often very well-justified!—for evidence of its harms. It’s perfectly fine to criticise something for being ugly or unpleasant, but that case can be made without exaggerating the strength of the data on what effects it might have. There’s nothing wrong with being a cultural critic. It’s just that cultural critics aren’t—and don’t need to be—scientists.

However, just because “porn made me do it” claims have been falsified in adults, the same can’t be said for children. Not only are kids known to be suggestible, but schools and the books individual children read form part of the all-important “non-shared environment,” which is almost as influential when it comes to character formation as parental genetics and social class.

Reading racist books as an adult is unlikely to make you a racist; that’s just not how people’s brains work. When it comes to kids, however, the jury is still out. Meanwhile, good luck getting ethics clearance when you do design a double-blind study capable of putting a media consumption hypothesis to the test in people below the age of majority.

Even if one sets Plato’s claim at its highest in the area where we know least—media consumption’s impact on child behaviour—there is still something more important to consider, something adults in developed countries teach (or should teach) young people: the difference between words and deeds.

It took centuries—even in the two great lawgiver civilisations, Rome and England—to habituate state power to punish crimes of violence against the person more harshly than crimes against property, or to treat verbal infractions (libel, slander, defamation) as civil wrongs and not crimes attracting a custodial sentence. We in the West view these changes as indicia of civilisation. We (rightly) criticise societies where people are still executed, imprisoned, or fined for apostasy and blasphemy.

This means it should be possible—for both children and adults—to draw a legible distinction between Roald Dahl’s words and actions. This is especially so when it comes to the accusations of anti-Semitism made against him from the early 1980s onwards.

During and after the 1982 First Lebanon War—when Israel invaded that unhappy country—Dahl began to make comments (in publications directed at adult audiences) of a sort common on the pro-Palestine left and familiar thanks to recent contretemps in Britain’s Labour Party. Jews, Dahl claimed, had “switched so rapidly from victims to barbarous murderers.” He went on to allege Jewish control of (or influence over) the press, and finally criticised Jewish support for Zionism and Israel while living in third countries like the UK.

This outburst invited offence archaeology in other areas, with people then combing through Dahl’s children’s books looking for barbs directed at other groups. His portrayal of women (in The Witches) was construed as sexist, while the Oompa-Loompas in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory were racist. When the offendotrons ran out of books to fossick around in, Dahl’s 11-year affair with set designer Felicity D’Abreu when still married to American actress Patricia Neal became comment fodder.

“The urge to censor the work of wicked people is natural to those whose worldview includes the conviction that people are representatives of their groups,” argues literary critic Iona Italia, “and that society is full of power struggles between groups—white and non-white; Western and Eastern; cis and trans; men and women. The relationship between writer and reader or painter and viewer is just one more struggle for dominance, and if the artist is or was an immoral person, we should therefore not allow their work to be celebrated because that would allow them to win.”

However, struggles for dominance of the sort Italia describes are not verbal, but physical. Here, another bad man—a man far worse than Roald Dahl—said a true thing, and no number of witty quips to the effect that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world or that the pen is mightier than the sword can gainsay it.

“Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” said Chairman Mao. A constitution may be full of soaring words, but without armed and hostile state power behind it, it is empty rhetoric. A civilisation may be glorious beyond measure, but without walls and borders to defend it, it will crumble.

Without the RAF’s victory in the Battle of Britain, the United Kingdom would have fallen to Nazi Germany, and there would be no European Jewish Holocaust survivors rather than some. Yes, Jews generally and Israelis especially are entitled to be distressed that Dahl went over so completely to the Islamist side. But he did fight actual Nazis, and his deeds outweigh his words. In that sense, anti-Semitism was a Messerschmitt up his arse, and he did his utmost to stave it off.