Argentina has the opportunity to rid itself of its omnipresent state. But such massive changes require long-term thinking.

Joseph Ellis's American Monologue

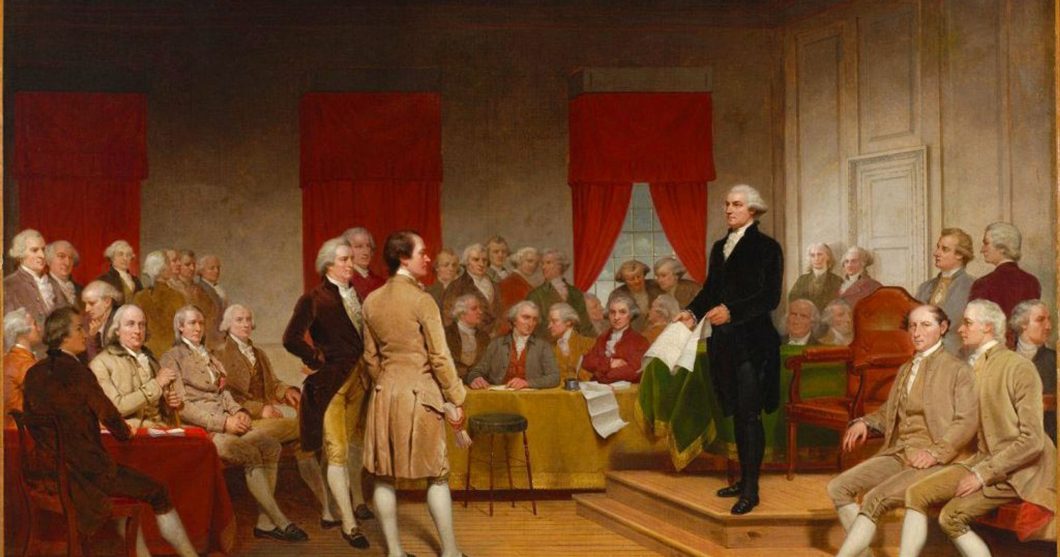

For many Americans, the Founding and first years of the republic remain a touchstone for politics. One can readily find analogies for practically every situation in this early history, yet the Founding’s legacies will always be contested. Despite significant disagreements in how to interpret the period, on the Right the Declaration and Constitution offer reminders that the goal of good government is to unite limited government with energy, as well as a salutary warning that no political compromise is morally pure. With similar internal debates, the Left has continually found an inspiration in the Declaration of Independence but struggles to balance a respect for the Constitution with their perception of its lingering injustice—to say nothing of the way the system itself fails to achieve egalitarian and democratic purity. We continue to orbit around the Founding; no velocity we achieve seems sufficient for escape.

Eminent historian Joseph Ellis has spent the majority of his long career studying the men that formed and led the nation in its early years. He knows their virtues and vices, and is well-positioned to craft an accessible book that grapples with how we might approach the Founding in light of present concerns—and in particular, one that shows the ways that people across the political spectrum still find inspiration in the words and deeds of the Founders.

There is no way such an effort could avoid a partisan vision. Ellis admits that every view is partial and that in the “writing of relevant history, there are no immaculate conceptions.” That said, he claims to aim at a basic sort of historical “detachment” and anti-ideological fairness. Unfortunately, Ellis’ latest book, American Dialogue: The Founders and Us, offers an argument tailored to deprive his political opponents of a usable Founding.

A Historian’s Creed

Ellis opens American Dialogue with a professional confession of sorts, an anxious embrace of ambiguity—one that offers a bit of insight into the assumptions he brings to the past:

Self-evident truths are especially alluring because, by definition, no one needs to explain why they are true. The most famous example of this lovely paradox . . . is the second paragraph in the Declaration of Independence . . . where Thomas Jefferson surreptitiously embedded the creedal statement of the American promise . . . .

My professional life as a writer and teacher of American history has been informed by another self-evident truth . . . . The study of history is an ongoing conversation between past and present from which we can all learn.

Ellis offers a bit of conventional wisdom here, but at the same time, he cannot quite bring himself to observe the deeper reasoning that Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin brought to writing and editing the Declaration. They did not secret away the “American promise.” On the contrary, they stated an axiom they believed to be essential to republican government, and offered common law reasoning that condemned an overreaching King and Parliament. In his famous 1825 letter to Henry Lee, Jefferson called the Declaration “the expression of the American mind,” a document that articulated a long-held Anglo-American tradition of theorizing about political resistance to tyranny. He recognized that to be worthy of self-government, citizens had to see themselves in a special way: as the kind of beings endowed with rights, deserving of respect, and upon whom political judgment depends.

Early in the book, Ellis identifies four obstacles to the American promise, and each of these four becomes the subject of a pairing between the past and present. To engage with the challenges of race in America’s transformation from a nation of European descent to a truly multicultural society, Ellis looks to Jefferson. Adams’ anxieties about oligarchy provide Ellis a mirror for the inequalities of our globalized world. For Ellis, our politics today is beset by the “sclerotic blockages of an aging political architecture,” and he turns to Madison for help to argue how misguided attempts to engage in constitutional textualism really are. A final chapter on foreign policy suggests that Washington might help us understand how America has become mired in “the impossible obligations facing any world power once the moral certainties provided by the Cold War vanished.” With each of these pairings, Ellis seeks to understand contemporary dilemmas in light of his chosen subjects’ experiences, and this approach delivers very mixed results.

Ellis believes the past to be usable, and he asserts that what people will make of it can be quite idiosyncratic—he offers several examples of how students believed their lives to be enriched by exposure to history in support of his own “self-evident truth.” But he also wants to tell a very detailed story that divides what he sees as the legitimate lessons of the past from those that are abuses. In particular, Ellis elevates the value of argument itself as the great lesson we ought to draw from the Founding. In Ellis’ view, it’s just fine for us to love and be inspired by the Founders, but not for anyone to use them in ways that might derail the march of progress.

Impossible Originalism

At the outset of his chapter on law, Ellis likens originalists to Christian fundamentalists, “both groups insisting that our lives in the present must be guided by principles embedding in language long ago and in the intentions or meanings of the authors of those sacred, or semi-sacred, words.” The historical background he offers to support this conclusion is essentially that because there was disagreement at the Founding, this “throws a cloud of confusion over all pursuits of the original meaning of the document itself, in part because his [Madison’s] position kept shifting, in part because the shifts were not voluntary changes of mind but rather mandatory adjustments to changing political circumstances.”

While the Constitutional Convention ought to provide a strong basis for Ellis to help us grasp the way Madison and others reasoned about law, instead he uses the historical record simply as a means to claim that the disagreements among the Framers convinced Madison that argument itself was what mattered. Thus Ellis claims that for Madison, “argument itself became the abiding solution, and ambiguity the great asset that ensured the argument could never end, making the Constitution an inherently ‘living document’ that successive generations would interpret in light of changing historical circumstances.” Nowhere does Ellis recall that one of Madison’s overriding goals was stability and the cultivation of the rule of law. He understands that Madison valued constitutional discourse—and that Madison thought it was vital for citizens to engage in—but his characterization of Madison’s reasoning about how and where this debate might occur and why it matters is particularly shallow.

As they debated the Constitution itself, and later the constitutionality of particular legislation thereafter, Madison and the other Framers understood that they were drafting with an imperfect medium that would require clarification through the practice of politics itself. They understood themselves to be establishing lasting principles of good government but also crafting a political process whereby a republican people could govern themselves. In Federalist 37, Madison writes,

All new laws, though penned with the greatest technical skill, and passed on the fullest and most mature deliberation, are considered as more or less obscure and equivocal, until their meaning be liquidated and ascertained by a series of particular discussions and adjudications.

But Madison held that the debate itself would and should occur among the educated public, among the people’s representatives, and between Congress and the Executive—not simply decided by fiat in the courts, a point which Ellis seems entirely unaware.

When Ellis moves from the Framers to the present day, he dedicates particular energy to an attempt to show that many of Justice Antonin Scalia’s opinions fail to respect history, and bears particular animus to Scalia’s opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller. The trouble is that Ellis misunderstands the lineage and practice of originalism almost as badly as he distorts Madison’s view of constitutional debate.

Ellis takes no account of any of the sprawling proliferation of the meaning- rather than intent-driven originalisms that now dominate the current debate. Indeed, he develops a potted history of originalism’s origins, dating it to an obsession with great books in “the curricular culture at the University of Chicago,” and Robert Bork’s yearning for a means to end the progressive stranglehold on constitutional law. But this ignores originalism’s lineage as an interpretive approach. Ellis ignores the degree to which the Framers themselves were committed to reading and arguing about constitutionalism with a sincere attention to the meaning of text alongside the imperatives of liquidation.

Rather than use history to show how progressive and conservative constitutional interpretation flow from historical experience, Ellis simply tries to deny that there ever has been such a thing as legitimate constitutional textualism. It’s less a genuine criticism of the originalist enterprise than an existential scream against the very idea that the Constitution offers enough legal clarity to present a genuine barrier to the legislative or executive branches.

And yet, almost comically, in the very same account of the Constitution which Ellis insists is riven by ambiguity and incapable of fixing meaning for present-day politics, he inveighs against the contemporary originalist view of the Second Amendment. By his telling, the debates surrounding the Bill of Rights and the Militia Act of 1792 should force us to view gun ownership only in the context of mandatory national service rather than individual rights. Therefore, he concludes that the Second Amendment offers no legal rights in the present day.

This willfully narrows the scope of the debate the First Congress held on this subject, where the assembled delegates never suggested that owning weapons could be restricted to members of the militia. It omits the representatives’ deep concern for giving citizens the right to employ arms as responsible citizens, for both “Common and Extraordinary” occasions—that is, usages ranging from hunting, through protection of life and property, and ultimately, armed defense of their liberties against tyranny. Neither the Founders’ intent in establishing the Second Amendment nor the original meaning of the discourse surrounding this fits with Ellis’ interpretation.

However, this distortion isn’t only a matter of partisanship on Ellis’ part: just as he does with the Declaration, he finds the idea that Congress may have intended to recognize principles they believed to be true in passing the Bill of Rights to be entirely unthinkable. Instead, he observes that Madison’s list of amendments, most of which became law, was simply

a codification of rights based on the previous thirty years of American history, most especially the lessons learned in opposing the policies of the British ministry in the run-up to the Declaration of Independence. What has come to be regarded as a set of timeless truths was, in fact, a distillation of the political experience of the revolutionary generation.

This ignores just how old and well-established the recognition of these principles were in Anglo-American constitutionalism, to say nothing of the broader European tradition of thinking about law in a principled way. He continues:

The special status the Bill of Rights has enjoyed over the ensuing years is in large part a function of its placement as a separate document, in effect an elegiac epilogue to the Constitution.

Against the entirety of the natural law tradition, Ellis appears in these passages to endorse the idea that practice cannot be informed by truth. Rather than being mutually exclusive, a prudential politics can and should be about both principles and experience—it must be. But where Madison aimed at establishing a lasting constitutional regime rooted in a frequent recourse to first principles, Ellis finds nothing more than the rough-and-tumble of political debate, whose principles are merely of historical curiosity.

The Historian’s Authority

Similar oddities abound in Ellis’ account of Thomas Jefferson’s relationship with questions of race and in his personal conduct. It is hard to dispute that “a racial fault line runs through the center of the American experience,” and “that issues of race and the legacy of slavery remain hotly contested.” Ellis also argues that Jefferson himself “straddles that divide with uncommon agility, making him our greatest saint and greatest sinner, the iconic embodiment of our triumphs and tragedies.”

This account places tremendous emphasis on Jefferson’s private life rather than his efforts as a thinker and statesman. Ellis offers the opinion that Jefferson was definitively the father of Sally Hemings’ children (and here declines to acknowledge the ambiguity that the most definitive commission of historians embraced on this question). In refusing to consider the alternatives, Ellis misses an opportunity for genuine moral complexity. For instance, if one of Jefferson’s relations fathered the Hemings children, is it better or worse that he kept them in bondage for so long? What might he have owed them?

Looking to Monticello’s design itself, Ellis writes:

When historians talk about the architecture of Monticello, they are almost always referring to the Palladian style that Jefferson had come to love during his travels in southern France. But the architecture of Monticello as a plantation is of a different genre altogether, and the design was distinctively Jeffersonian, meaning structured to make the black workforce almost invisible and to feature the light-skinned household laborers, who looked and acted less like slaves than members of the family because, in fact, they were.

Ellis offers no evidence for this observation; the paragraph in which it appears lacks any citations. Without seeing Jefferson’s own words on the subject, how can we really know what Jefferson intended with the design? And moreover, are we to believe that this allowed Jefferson respite from his own moral compromises?

Jefferson should be difficult to love, and Ellis is right to show us why. But is he—or James Baldwin, to whom he places Jefferson in dialogue—an adequate guide to the challenges of dealing with the tremendous diversity of 21st century America?

Ellis surveys what Jefferson wrote and thought about questions of race and how they related to his view of rights, but his judgments on this seem as filled with chronological snobbery as his understanding of self-evident truth. By the historian’s telling, Jefferson “opposed slavery not because it was a sin, but because it was an anachronism.” This completely misunderstands the moral universe within which Jefferson operated, and ignores Jefferson’s own words in Notes on the State of Virginia—“Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever”—and in so many other works.

But let’s imagine Ellis is right for a second. If “dialogue” rather than moral truth is all there is, Jefferson’s example as a man seems an uncommonly poor guide to a moral life. If, on the other hand, he spoke the truth while living it poorly, there is still much to learn.

The Lessons of History

Ellis occasionally offers perceptive insights into either the nature of his historical subjects or the lasting lessons we ought to draw from them. His analysis of Adams and Jefferson’s musings on the power of oligarchy and the possibility of a natural aristocracy is superb, as is his depiction of Washington’s failed attempts to get Americans to respect their treaties with Native Americans. He links the former to a tendentious narrative about American inequality without once asking whether as a matter of principle inequality is actually the great evil he imagines it to be or questioning the costs that ending inequality might impose on our society’s great—and widely-shared—wealth. In writing about Washington, Ellis offers hard truths about our nation’s undeniable failure to respect treaties with the tribes, and puts this in service of a kind of realist argument endorsing restraint in American foreign policy.

The weakest sections of the book appear in Ellis’ attempts to grapple with current events. Instead of choosing frames for his arguments that would highlight a genuine dialogue using the past, he consistently leans toward partisanship rather than giving his opponents a fair hearing. This isn’t that surprising, since from his perspective, the great debates of American life have been fatally undermined:

We currently inhabit a second Gilded Age in which the active interplay within that dialogue has almost completely disappeared because belief in a prominent role for government has been placed on the permanent defensive, in part because one side enjoys the advantage of a very large and expensive megaphone that amplifies its message.

To say the least, this suggests that Ellis has a rather circumscribed notion of what “argument” entails, one that seems oblivious to the Left’s significant advantages in education and culture.

Developing an excess of certainty about one’s interpretation of a murky historical record—what Ellis derides as “law office history”—shouldn’t be the go-to approach for a book that purports to show the importance of dialogue, yet the method appears in large and small ways throughout, usually in service of the overarching themes of the book. The most jarring such example comes at the end of his treatment of George Washington. In service of concluding his otherwise-thoughtful chapter on our first president as a consummate realist, Ellis argues that the absence of clergy at his deathbed and instructions to wait three days for his burial obviously means that Washington believed “there was no such thing as heaven, either on this earth or elsewhere,” and that he clearly was not a man of any faith. Given the reticence at the time toward overtly religious talk—Christians did not speak so volubly in the terms they do today—this seems overdrawn to say the least.

By claiming to encourage and then artificially closing off a robust debate about the past’s meaning, Ellis produces a monologue and thinks it an actual discussion. This is a shame, if only because the actual struggles among the Founders offer so much insight into the challenge of creating and maintaining institutions even with an understanding of first principles, and the real dialogue between our world and theirs offers so much more lively a challenge to our political and social life than he would permit.