America needs religious traditionalists, and they need their classically liberal allies.

Anglifying American Conservatism

When it seemed that conservatism was finally settling into some defined boundaries under the presidency of Donald Trump, however fitfully—into Trump alt-populists, Never Trump former neocons, establishmentarian veterans of the two Bush administrations, expert/reform conservatives, social communitarians, big L libertarians, and a residue of libertarian-conservative fusionists—here comes Anglo-American Toryism as the proper resolution.

The driving force is the political theorist Yoram Hazony, who heads the Jerusalem-based Herzl Institute. His work has been prominently featured in the Wall Street Journal, Mosaic, and American Affairs (with Ofir Haivry), among other publications.

In his article “Is Classical Liberalism Conservative?” (Wall Street Journal, October 13, 2017), Hazony finds “two camps” on the Right that have “an unbridgeable ideological chasm” opening between them. One is identified with Charles Krauthammer, William Kristol, and Robert Kagan, who idealize an over-rationalized universalistic democratic spirit headed by a U.S. “benevolent global hegemony.” One starts to think he must mean neoconservatives. But soon these writers are joined by John Locke, Ludwig von Mises, F.A. Hayek, Milton Friedman, Robert Nozick, and Ayn Rand—and all nine are labeled rationalistic “classical liberals.”

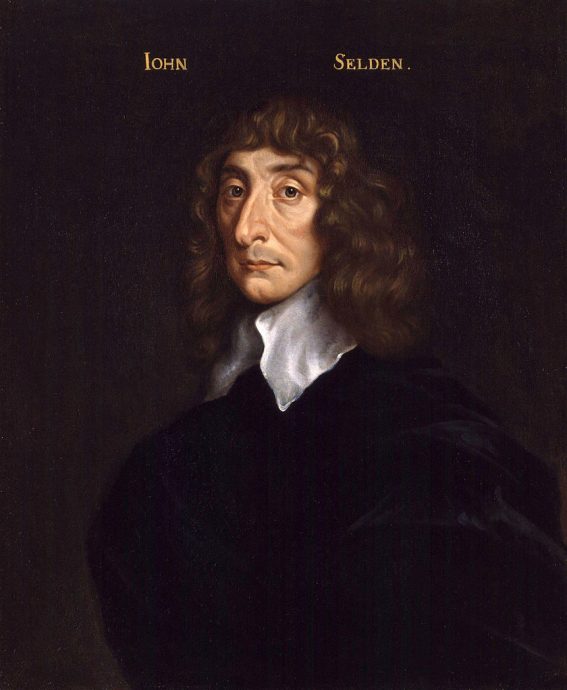

Against this group Hazony arrays Sir John Fortescue, John Selden, the Baron de Montesquieu, Edmund Burke, Joseph Story, and Alexander Hamilton, under the rubric of “Anglo-American conservatism.” These supported individual liberty, balanced executive-legislative relations, bicameral legislatures, jury trials, due process, the bill of rights, and “Protestant institutions such as the independent national state, biblical religion and the family.” Rights were accepted but empirically based upon historical trial and error rather than universalistic political ideals.

The threat of communism unified these two strands under William F. Buckley and Frank Meyer’s fusionist conservatism; but when the Berlin Wall fell, so did the coalition. The classical liberal strand then came to support “a new world order” spear-headed by the United States that tried to bring democracy to the world. This plan was undermined by China, Russia, and radical Islam, while the banking crisis and the disintegration of the family undermined capitalism, until it came a cropper with Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, “paving the way for a return to empiricist conservatism” as supported by Hazony.

Neoconservatives, reformist experts, Bush moderates, Friedman libertarians, Hayekian spontaneous evolutionists, and Randian objectivists have all reached the same conclusion in reacting to the Journal article. Many whom he calls classical liberals would reject the label. His more detailed piece in the Summer 2017 edition of American Affairs, coauthored with Haivry and entitled “What Is Conservatism?”, more fully develops the intellectual case for Anglo-American conservatism. This second piece is sure to anger them even more.

To Hazony and fellow political theorist Haivry, the Anglo-conservative and classical liberal factions are led by Fortescue and Locke, respectively.

The jurist Fortescue (c. 1394–1479) was chief justice of Britain’s high court and ended as exiled chancellor, since, having been on the losing side of the War of the Roses, he was forced to write his classic 1616 In Praise of the Laws of England in France. Fortescue held there that the English constitution limited the powers of the monarch under the traditional laws of England

in the same way that the powers of the Jewish king in the Mosaic constitution in Deuteronomy are limited by the traditional laws of the Israelite nation. This is in contrast with the Holy Roman Empire of Fortescue’s day, which was supposedly governed by Roman law, and therefore by the maxim that ‘what pleases the prince has the force of law,’ and in contrast with the kings of France, who governed absolutely.

Fortescue laid out “what later tradition would call the separation of powers and the system of checks and balances.” He linked “the character of a nation’s laws and their protection of private property to economic prosperity, arguing that limited government bolsters such prosperity, while an absolute government leads the people to destitution and ruin.” His work, adds Hazony and Haivry, “even as a firm pre-Reformation Catholic breathes the spirit of English nationalism—the belief that through long centuries of experience, and thanks to a powerful ongoing identification with Hebrew Scripture, the English had succeeded in creating a form of government more conducive to human freedom and flourishing than any other known to man.”

From there they hasten through two centuries to the “greatest conservative,” Selden, and his 1628 Petition of Right, rushing past the post-Reformation civil war fought between royal Calvinist traditionalists and legislative Puritan and Presbyterian reformers, to get to the “restoration of a Protestant monarch” by a Parliament “united around Seldenian principles” in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which reaffirmed the “traditional English constitution” protecting England’s “religion, rights and liberties.”

The fly in the ointment of this conservative restoration was the rationalist “radical” liberal, John Locke (1632-1704). Locke, they write, was known as an empiricist “but his reputation in this regard is based largely on his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), which is an influential exercise in empirical psychology.” Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, rather than being empirical “begins with a series of axioms that are without any evident connection to what can be known from the historical and empirical study of the state.”

Locke’s assumptions of “perfect freedom” and “perfect equality” in the Second Treatise are said to be merely rationalistic and ideological, and to contradict experience. This liberal idealism advanced significantly in post-1688 England and later “finds rather dramatic expression” in the Americans’ Declaration of Independence, “famous for resorting, in its preamble, to the Lockean doctrine of universal rights as self-evident.” While contested by Hamilton, the election to the presidency of the Declaration’s author made Lockean liberalism “increasingly dominant in America.”

They address the Constitution’s “deviation from English tradition in the matter of a national religion” by discussing the views of Joseph Story, which they characterize as “appropriately balanced.”

On the one hand, Story “confirmed ‘the right of private judgment in matters of religion, and of the freedom of public worship according to the dictates of one’s conscience’ as an integral part of the nation’s constitutional heritage.” On the other, he “asserted the traditional Anglo-American conservative view that ‘the right of a society or government to interfere in matters of religion will hardly be contested by any persons, who believe that piety, religion, and morality are intimately connected with the well-being of the state, and indispensable to the administration of civil justice.’ ”

The Haivry/Hazony principles of Anglo-American conservatism are summarized as:

1) Historical Empiricism: The authority of government derives from constitutional traditions known, through the long historical experience of a given nation, to offer stability, well-being, and freedom.

2) Nationalism: The diversity of national experiences means that different nations will have different constitutional and religious traditions.

3) Religion: The state upholds and honors the Biblical God and religious practices common to the nation.

4) Limited Executive Power: The powers of the king (or President) are limited by the laws of the nation, which he neither determines nor adjudicates.

5) Individual Freedoms: The security of the individual’s life and property is mandated by God as the basis for a society that is both peaceful and prosperous, and is to be protected against arbitrary actions of the state.

They write that while they believe in limited government and individual liberties, they “also see clearly” that “the only forces that give the state its internal coherence and stability, holding limited government in place while staving off authoritarianism, are our nationalist and religious traditions.” And, they add, “These nationalist and religious principles are not liberal. They are prior to liberalism, in conflict with liberalism, and presently being destroyed by liberalism.”

Yes, they are prior; but one cannot fail to note that they are prior to Fortescue too. In this English-oriented discussion Magna Carta is missing—but one can see why. Emphasizing it would not have allowed the simple liberal/conservative dichotomy that is at the center of the two articles.

Locke is critical here. He is certainly rationalist but is also empirical, as Hazony and Haivry somewhat concede, but in addition to both, Locke also accepted revelation—indeed wrote that an evident one should be accepted over reason. It was this belief that led Leo Strauss, in Natural Right and History (1953), to exclude that part of Locke’s thinking as irrational and only deal with Locke’s rational “partial” natural law. Hazony and Haivry do the same thing but for the opposite reason.

Their view is clearly too dominated by a view of the Anglo experience as simply Protestantism when it was in fact divided even into civil war in England. The Mosaic piece by Hazony likewise assumes a single national religion in early America in spite of Puritan, Baptist, Quaker, Anglican, Presbyterian and even Catholic colonies.

It is critical to the American experience that its colonists had left behind an England that was still defined by the Magna Carta—with memorials to it across the states but, according to Daniel Hannan, without a single such in England before its 800th anniversary (except one by the American Legion). Lord Baltimore petitioned to have Magna Carta printed in his Maryland charter but was denied by English authorities. William Penn was actually successful many years later.

Nor can it be denied that Locke was preeminent in the minds of the great majority of America’s Founding Fathers—the only academic argument being whether he was the only or a major inspiration.

Hazony’s typology just will not fit. Consider those five principles. Historical empiricism heads the list but is the essence of Hayek’s views, as one example—yet Hayek is considered ideological, categorized that way on the strength of a single 1939 quote. In fact, Hayek wrote an essay in 1964 called “Kinds of Rationalism” to distinguish his (and Locke’s) non-ideological rationalism from that of Rene Descartes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Numbers 2 and 5 would have been obvious to Locke and to most, if not all, of the others. Number 3 would probably be rejected by all, including the religious Buckley—especially Story’s words to the effect that “the right of a society or government to interfere in matters of religion will hardly be contested by any persons.” Even number 4 equating the executive power of king and President can only seem strange to Americans since the Queen has comparatively none.

Clearly the religious question is critical for these authors. There are libertarians, leftists, and others who absolutely reject religion in public life, to be sure; but most Americans are at the very least leery of the state’s “upholding” religion leading to the state dominating religion, as it did in Europe. Hazony and Haivry do make a contribution by separating rationalistic from more empirical thinking, but then they do violence to that distinction by over-rationalizing Locke and Hayek, especially. As for the rest, there are good reasons to separate the various “classical liberal” factions that do not rest easily within two categories, a simplification that they themselves point to near the end of their article.

If there is to be some commonality for conservatism, it would require a true synthesis of differences and probably could not include everyone who goes by that designation. Philosophical fusionism was in fact revived historically by Hayek, which stimulated Buckley and Meyer to develop a synthesis of freedom and tradition into a modern American conservatism that was successful for a generation. As Buckley himself observed in the declining George W. Bush days, that synthesis had “attenuated” and would need to be re-fused for a coherent future conservatism—although perhaps only for this side of the pond.