The consumer welfare standard for antitrust regulation is under assault, leaving a situation where "the Government always wins."

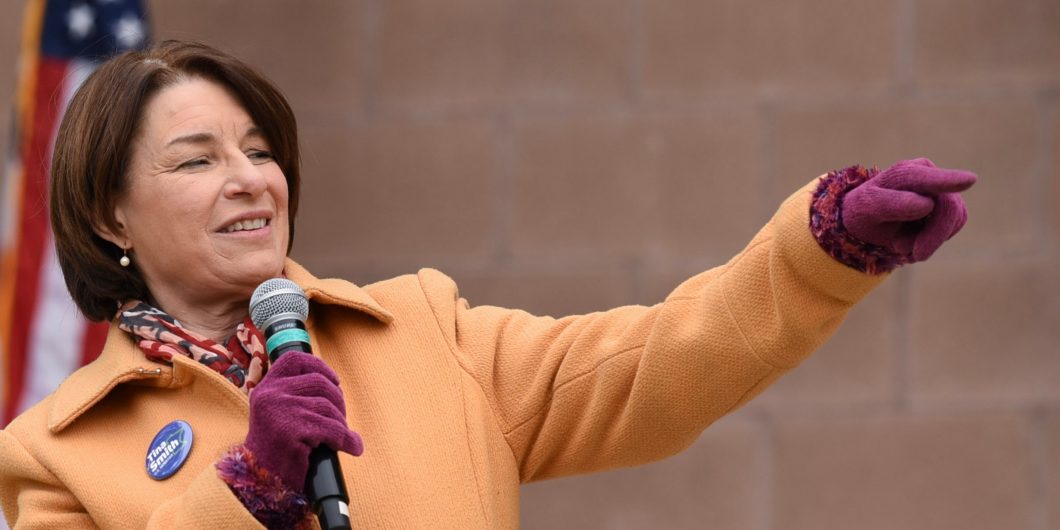

A Prairie Populist Rises Again

In her new book, Antitrust: Taking on Monopoly Power from the Gilded Age to the Digital Age, Senator Amy Klobuchar leaves no doubt as to who are the heroes and who the villains in America’s economic history. The heroes are hard-working Americans, farmers, miners, and union members, who have been exploited for more than a century by corporate robber-barons, oligarchs, and monopolists, spanning from Rockefeller to Zuckerberg, aided and abetted by lobbyists, Republicans (except TR, sort of), and worst of all, conservative judges. We, the People, are the Morlocks. They, the Monopolists, are the Eloi. To stop them, we must enact new laws to give the government much more control over the economy.

Even if one questions this stark historical narrative, this is an important and often entertaining book. Senator Klobuchar chairs the Senate Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights and therefore helps to shape the nation’s economic policies. Her book squarely lays out the progressive case for reworking the nation’s antitrust laws, and in so doing, provides insights into progressive thinking. Whereas free market capitalists see a dynamic economy that is producing remarkable new technologies at low prices, progressives see exploited workers and outrageous corporate profits. This book explains her perspective and policy ideas. Along the way, she relays countless historical anecdotes, such as how a monopoly helped to spur the American Revolution and how a merger dispute cost one party the presidency.

And there’s another reason to read this book: a fair reading leaves little doubt that the senior senator from Minnesota is not yet ready to concede the 2024 (or perhaps 2028) Democratic presidential nomination to Vice President Harris.

Antitrust History

As the book relays, antitrust issues have been integral to the nation’s history. “In the British Empire, the monopolies conferred by Parliament were the product of corruption, influence peddling, and outright bribes,” (not unlike the consequences of government intervention in markets today). In Klobuchar’s telling, after Parliament handed control of the tea market over to the British East India Company, Americans resisted via the Boston Tea Party and ultimately the Declaration of Independence, which represented “an act of economic rebellion against monopoly power” (conferred by the government).

Monopoly concerns spurred another famous schism, this one between the first President Roosevelt and his successor. In 1907, Roosevelt informally agreed not to sue U.S. Steel under the Sherman Act, in exchange for the company’s help in stabilizing the stock market. In 1911, ignoring this gentlemen’s agreement, President Taft’s Justice Department sued U.S. Steel for acquiring a large competitor. According to the book, this lawsuit exacerbated the personal rift between Roosevelt and Taft, leading to Roosevelt’s third-party challenge in 1912, the split Republican vote, and the election of Woodrow Wilson, who campaigned on a song titled, “Bust the Trusts.”

For Senator Klobuchar, antitrust is very personal. She contrasts her ancestors, who worked as iron ore miners, with corporate titans such as Minnesota’s James J. Hill, who created the Great Northern Railway and who profited from her ancestors’ labor. “Two generations of the Klobuchar family had worked underground in servitude to the mining interests.” “Unlike James J. Hill, the Klobuchar family owned no railroads.” “As a little girl growing up in the Twin Cities, I never got to go inside [Hill’s 36,000 square foot] house until it opened for public tours.” Although some may describe her views as generational class envy, Klobuchar is absolutely sincere in believing that owners and executives earn too much and workers too little. (My own family history might provide a different lesson: two of my uncles were coal miners; that income allowed all five of their children to attend college, four to earn advanced degrees, and three to become medical doctors).

Klobuchar blames a failure of antitrust law for “too much business consolidation in this country.” Klobuchar, an attorney and alumnus of the University of Chicago Law School, excoriates what is now known as the “Chicago school” of antitrust thinking, which focuses on economic efficiency and consumer welfare, rather than on the number and size of competitors in a particular market. In Klobuchar’s telling, the Chicago school and its chief proponent, Robert Bork, “grossly perverted the whole history of the Sherman Act, which was to protect American farmers and workers and consumers from the power of monopolists.” She describes Bork’s consumer welfare standard as “bizarre.” In her view, the Chicago school’s failure to promote competition has led to high cable rates, airline fares, drug prices, seed and fertilizer costs, and income disparities. (As a fellow alumnus of Chicago Law, I can’t help but wonder who taught Klobuchar antitrust. My guess is that it wasn’t such Chicago luminaries as Richard Posner, Richard Epstein, or Frank Easterbrook, but instead some visitor from Yale, or possibly even Berkeley. Who knows, but for a scheduling conflict, perhaps Klobuchar would have become a Republican!)

Klobuchar makes some fair points about antitrust law. She is right that the authors of the Clayton Act, an early companion to the Sherman Act, wanted to protect small companies and forestall economic concentration, and that antitrust law today does not concern itself with these issues. Unfortunately, Klobuchar does not explain why the courts, with more than a century of experience, eventually found it both impossible and unwise to punish companies based on their size and profit margins. Such criteria proved unworkable and harmful; indeed in the 1960s, LBJ’s antitrust chief, Donald Turner, warned against using the antitrust laws to attack bigness per se.

Klobuchar also makes some claims that are demonstrably false, if not outright troubling. She wrongly asserts that the consumer welfare standard ignores prices paid by actual consumers, when in fact today antitrust concerns itself first and foremost with the possibility of price hikes, along with non-price competitive factors such as quality. She also repeatedly attacks the courts in ways that some may find concerning coming from a member of the august Senate Judiciary Committee. “[T]he extreme views of Gorsuch and Kavanaugh on antitrust issues were one of the many reasons why I fought so hard to keep them off the Court.” Socialist leader Eugene Debs “had good reason to believe that the courts were carrying the water for big business.” Et cetera.

Exchanging Big Business for Big Government

Turning to the future, Klobuchar’s policy proscriptions far exceed the scope of antitrust law—befitting the once and possible future presidential candidate. She writes, for instance, that “We should be investing more in clean energy and green jobs. It is far better for us, as a country, to invest in farmers in the Midwest than in oil sheikhs and oil cartels in the Mideast.” You can hear the applause from the caucus-goers in Des Moines. In nods to progressives, Klobuchar calls for the repeal of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, other election changes such as paper ballots and “clear rules of the road for political advertising and truthtelling on major internet platforms,” net neutrality, immigration reform, government price negotiations with drug companies, and more capital for women and minority-owned businesses. Bowing to labor unions, Klobuchar wants a $15 minimum wage, an end to right-to-work laws, and tax reform to “ask our wealthiest citizens to pay their fair share of taxes and that would strengthen labor unions.”

Klobuchar’s worst proposals would move the United States towards a sort of mother-may-I economy, where private companies would have to seek the government’s permission before doing much of anything.

When it comes to antitrust, Klobuchar presents a wide spectrum of ideas. Quite a few make sense and could form the basis for some bipartisan compromise. She wants to provide more funding for the antitrust agencies, which has lagged over time, and focus resources on ways to help lower-income consumers and minorities. She also aims at overly aggressive non-compete clauses, which can hamstring hourly workers. For instance, she notes that Jimmy John’s once forbade its employees from taking jobs with competitors for two years. With due respect for these skilled sandwich artists, neither da Vinci nor van Gogh ever faced such severe post-employment restraints.

Unfortunately, many of Klobuchar’s more aggressive ideas would seriously damage the nation’s economic dynamism. She would reverse the burden of proof for certain mergers by requiring the merging parties to prove that an acquisition enhances competition. (Currently, the government must prove that an acquisition harms competition.) She also would allow the antitrust agencies to seek enormous civil fines for violations of the Sherman Act based on a company’s revenue, untethered to actual harm to consumers, and on top of existing remedies such as treble damages. These sorts of proposals could discourage companies from routine, pro-consumer conduct and would move the United States towards a sort of mother-may-I economy, where private companies would have to seek the government’s permission before doing much of anything.

Indeed, Klobuchar expressly wants the United States to model Europe. In her view, “American antitrust enforcers must be much more vigilant in monitoring high-tech companies, just as European officials have been in investigating and monitoring any potential antitrust transgressions.” Although Klobuchar attended the finest law school in the land, she apparently never studied the law of unintended consequences. Can you couple America’s dynamic and innovative economy, home of the world’s largest and most successful tech companies, with Europe’s burdensome legal and regulatory regime, one that punishes “abuse of dominance”? Europe’s tech sector, which lags far behind ours, suggests not. The Council of Economic Advisers has explained that overly aggressive merger review could harm the economy by reducing venture capital funding for start-ups. America’s tech sector leads the world, at least in part, because we have created a legal, regulatory, and financing regime that encourages and rewards innovation. Should Congress turn America into Europe because of some frustrations with Big Tech, even as major antitrust cases are already pending in court?

Klobuchar’s proposals are also rife with contradictions. For example, Klobuchar rightly decries the numerous industries that have been exempted from the antitrust laws, ranging from Major League Baseball to anti-hog-cholera serum. As she explains, “even a cursory review of the legislative and judicial history of America’s antitrust exemptions—one peppered with backroom deals in the halls of Congress—demonstrates that this area of law is, at its best, incoherent and confusing, and, at its worst, corrupt and unfair.” Nevertheless, she then proposes to create yet another antitrust exemption for a favored industry, news publishers, to bargain collectively (read: fix prices) with tech platforms. She correctly criticizes overly aggressive non-compete clauses for limiting worker freedom, then calls for an end to right-to-work laws. She condemns China for using antitrust to protect its domestic industries but then praises Europe, which frequently uses competition policy to engage in rank protectionism.

In perhaps the richest irony, Klobuchar apparently fails to appreciate that her proposals would dramatically increase the authority of the one entity whose power is nearly impossible to dislodge: the federal government. Viewed in totality, Klobuchar’s historical analysis actually undermines her case for giving the government more discretionary authority. For instance, Klobuchar generally admires Roosevelt but relays that he politicized antitrust enforcement. “William Randolph Hearst would expressly complain about what he called ‘the Roosevelt method,’” she tells us. “The Roosevelt method,” according to Hearst,

was to divide the trusts into good trusts and into bad trusts and to go to extreme lengths in assailing those that were declared by him to be the bad trusts, and to equally extreme and sometimes illegal lengths in aiding and protecting those that were declared by him to be the good trusts.

“The good trusts,” he noted, “were the trusts that politically supported Roosevelt and the bad trusts were the trusts that politically opposed Roosevelt.”

How can Klobuchar discount the very real possibility that her proposals would lead to more of the same? It is true that progressives generally fear excessive corporate power and that conservatives fear excessive public power, but Klobuchar repeatedly and rightly highlights instances in which government played favorites in the antitrust space. Past is prologue, no?

Senator Klobuchar deserves credit for writing a thoughtful and engaging analysis of antitrust law. No one can begrudge her seeking to use her committee perch to set forth a national political platform. But as shown by her review of TR, the British Empire, and anti-hog-cholera serum, policymakers of both parties should exercise caution before they give the government even more discretion to police our economic freedoms.