A Shotgun Wedding

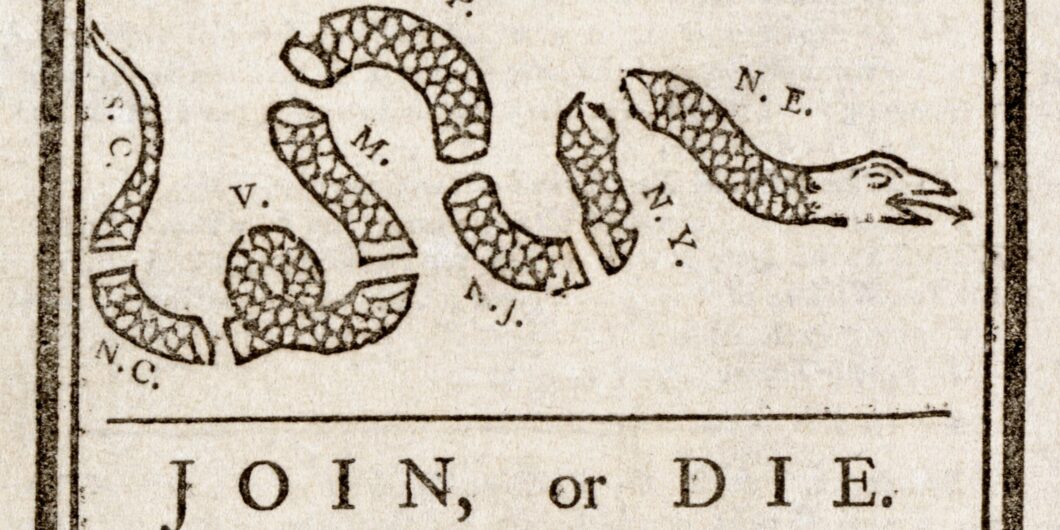

Anyone who has seen the HBO miniseries on John Adams will likely remember the opening credits sequence. Music plays in the background that seems a mashup of lush Hollywood overture, colonial folk song, and martial drumbeats. The screen fills with the image of a flag gently waving in the wind. On the flag is pictured a segmented snake, each segment representing a state or region in colonial North America. At the bottom of the flag is the simple yet portentous motto, “JOIN, or DIE.”

Surprisingly, this flag was not born out of the Revolutionary period; it was designed in 1754, probably by Benjamin Franklin. At the time, Franklin feared that the colonies’ disunited condition made them vulnerable to aggressions by the French. That same year, Franklin essayed a draft Articles of Confederation, written under the prevailing assumption that the colonies might form a union under the protection of the British crown.

But this theme, that the colonists’ very survival depended on union, only intensified in the years leading up to the rupture with Britain. John Dickinson’s enormously popular “Liberty Song,” written in 1768, included the lines: “Then join hand in hand, brave Americans all! By uniting we stand, by dividing we fall!” Once war commenced, fears of fracturing only intensified.

Eli Merritt deftly explores these themes in his new book, Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution. What other studies on America’s War for Independence commonly leave in the background, Merritt brings to the fore: the centrifugal forces of regional selfishness, mutual jealousies, and sometimes barely-disguised hostility that were giving the lie to the rebels’ declared identity as the United States of America.

Merritt admirably achieves what he sets out to do. Furthermore, he is a wordsmith of the first water. If it is reasonable to say that a fair test of an author’s skill is his ability to write engaging prose about drying codfish on the shores of Newfoundland, then this author passes the test with flying colors.

“The founding of a single United States,” Merritt points out, “was hardly the easy marriage of thirteen homogeneous, liberty-loving states so often depicted in American history.” A better metaphor, he suggests, “is that of a shotgun wedding.”

Disunion as the Absence of Union

But what, exactly, does it mean to be disunited? In one sense, disunion merely expresses the absence of union. To understand it in that sense, it would be necessary to first understand the meaning of union. And in the years during and immediately following the War, there existed radically different opinions regarding the sort of union that would be possible or desirable between the states. For that reason, the meaning of its negation, disunion, can be subjective, relative to one’s expectations for union.

Many of the leading figures at this time were seeking nothing more cohesive than a temporary military alliance. Indeed, several of those waving “JOIN, or DIE” flags would have been content with even less—with the mere outward appearance of a military alliance, even if it belied the reality. If they successfully achieved union under those loose terms, however, it would constitute disunion for the more continentally minded, who sought a permanent confederacy of commercial trading partners.

Far more anachronistic would be to measure disunity against a standard of union that would not exist in this country for centuries yet to come. Yet the book at times appears to view the subject through that lens.

In 1777, Merritt tells us, members of the Continental Congress were disagreeing “on the very meaning of independence as proclaimed in the late declaration. Were the ‘United States of America’ one independent republic or thirteen separate ones …?” But, really, was anyone seriously asking if the United States was a single republic in 1777?

Elsewhere, the book describes how loyalists argued that they must continue under the superintendence of England, because it was necessary to have “one supreme legislative head in every civil society,” and all other individual or political members “must be subordinate to its supreme will.” The colonists rejected that argument in 1776, but “this is precisely the organizing principle that the founding fathers returned to and ratified in the U.S. Constitution of 1787.”

Is it true that the 1787 Constitution established Congress as the “one supreme legislative head,” and the state legislatures were “subordinate to its supreme will”? Unquestionably, the most nationalistic Framers, such as James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, had wanted to craft such a constitution. But it is equally undeniable that Madison as well as Hamilton were bitterly disappointed by their failure to do so.

To the extent that disunity means an absence of union, Disunion sometimes underestimates the degree of disunion prevailing at this time, and it overstates the impetus for consolidation. The book sometimes presupposes that, once the unruly or irrational forces of disunion could be overcome, a strong national union would be the natural and inevitable consequence. It fails to appreciate that there were some equally legitimate fears of union. Several more loose-jointed forms of union were a distinct possibility at this time, and many believed they would have been preferable.

The Abolitionist Counter-Factual

Nowhere does the book appear more anachronistic than its treatment of slavery. After acknowledging that leading antislavery advocates did not dare attempt a federal solution to the problem of slavery—for fear that any attempt might precipitate a permanent rupture between the states, perhaps driving them “into bloody mayhem”—the book indulges in the hypothesis that a different approach might have succeeded in achieving general abolition without the horrors of civil war.

The Founders “faced a stark choice in the 1770s and 1780s. They could either advance a federal program for liberating black Americans from slavery, or they could secure freedom from civil wars for themselves. They chose the latter, making a grievous devil’s bargain.”

But is it plausible to suppose that advancing a federal program for abolishing slavery was a realistic choice—a road not taken—for statesmen living in the 1770s and 1780s? To imagine this scenario is to presume there existed both greater unity and greater public spiritedness than the historical record would suggest. Every page of Disunion Among Ourselves provides a fresh refutation to the proposition that such a choice ever existed. At every turn, it seems, “regional selfishness overwhelmed public interest.”

True, a few individual statesmen might be found who placed considerations of the common good above local interests. But not once in these chapters do we find an example of an entire state acting with high-minded magnanimity.

Americans finally learned that nothing cements union better than resistance to a common enemy. And if any hero emerges from this tale, it is John Jay.

An alternative that would have been impossible to put into practice is not properly named a choice. The thought experiment which imagines that states might suddenly and unaccountably act contrary to their invariable practice is examining history through the lens of our contemporary wishes rather than their contemporaneous circumstances.

Yet these occasional flashes of anachronistic analysis do not dominate the narrative; they are by no means a fatal flaw within this otherwise superb book.

Disunion as Discord

If the word disunion may mean, simply, an absence of union, it may also mean discord and dissension, or even hostility and warfare. The book convincingly shows that one strong motivation for forging a lasting Union was the fear that failing to do so would eventually result in wars between the states—domestic hostilities that foreign powers would be quick to exploit.

Nevertheless, fears of disunion were sometimes met with equally credible fears of union. Concentrate power too much, some cautioned, and the newly independent states might create the same centralized tyranny they sought to flee. Rushing into union too quickly might trigger the very rupture they sought to avoid. And some revolutionaries, such as Sam Adams, believed that attempting to force a union among states evincing such incompatible interests, habits, and beliefs might eventually lead to a bloody civil war.

One possible solution was to unite the different regional interests into two or three separate confederacies. Few doubted that the states of New England were destined to form a lasting compact. Tellingly, the head of the segmented snake in the “JOIN, or DIE” flag represented New England; all the other segments represented individual states.

One important lesson in this book is that a seemingly unbridgeable gulf between the perceived interests of the North and South existed long before the divisions over slavery would swell into such consuming significance in the nineteenth century. At this time, however, it was conceivable that the Middle states might find more in common with the South than with New England. The New England colonies were distinct from the rest of North America, and they were more homogenous among themselves in their religious commitments, political opinions, and commercial interests.

New England representatives were then insisting that no peace treaty would be acceptable unless they retained the fishing rights they had enjoyed as colonies. New England’s uncompromising position outraged the Middle states as much as the Southern states. John Dickinson, then a delegate from Pennsylvania, expected New England would eventually initiate the rupture. These former colonies, he predicted “would disunite from the rest at the Hudson River.”

The Southern states, for their part, believed that a sine qua non to any lasting peace was securing navigation rights on the Mississippi River. New England was jealous of the burgeoning commercial prospects of the South. The Middle states, by contrast, could be persuaded to share the enthusiasm for westward expansion, so long as the South could be persuaded to share the spoils.

Maryland refused to confederate with the other states until Virginia agreed to give up its massive land claims, a tract of western territory nearly the equivalent of all other colonies combined. Virginians refused to relinquish so valuable an interest . . . that is, not until a troop of redcoats marched toward Richmond. Indeed, the only time any state showed a willingness to abandon its claims of commercial or territorial self-interest were in those brief and terrifying moments when the higher claims of self-preservation were at stake.

While mutual indifference to the interests of other states could be overcome by sectional bargains and compromises, mutual jealousies could not. It was an open secret that many Northerners, such as Gouverneur Morris and John Jay from New York, privately hoped that Southern states would be denied access to Mississippi ports. They feared that cheap land in the southwest, combined with an open trade route on the Mississippi, would spark a mass migration that might enrich that region at the expense of the northeast.

Uniting over Common Enemies

Americans finally learned that nothing cements union better than resistance to a common enemy. And if any hero emerges from this tale, it is John Jay.

Southerners had been unhappy with Jay’s appointment as minister to Spain, (rightly) suspecting that he did not have their best interests at heart. But the contemptuous treatment he received at the court of King Charles III could not be better calculated to break down his regional prejudices and spur his national pride.

Spain not only determined to deny free trade on the Mississippi to the American states; she also wished to dangle the false hope that an accommodation might be forthcoming. In this way, she enjoyed the double advantage of weakening the South commercially and sowing discord between the states.

When Jay was later appointed as one of the peace commissioners in Paris, he found that even France could not be trusted to prioritize the interests of the United States over its own. For years, many Americans suspected that France coveted the northernmost reaches of North America—not only Canada, but also the upper Ohio Valley, and perhaps parts of Vermont. They feared that Spain and France might negotiate a peace with Britain that would divide the sparsely inhabited territory of North America between them.

While in Paris, Jay became convinced that France was double dealing and secretly supporting Spain’s new and expansive claims to land east of the Mississippi—right up to the Appalachians. Some historians have judged that Jay’s suspicions might have been more than a mad fever dream. It may have been true that the unofficial policy of the most powerful forces in Europe was to divide and conquer the North American states.

Under these impressions, Jay had a change of heart regarding the importance of the Mississippi. By this time, the Confederation Congress seemed willing to relinquish almost every former ultimatum to attain peace and independence at any price. But Jay was now ready to risk his reputation and defy Congress for the sake of securing the Mississippi for the South. Almost single-handedly, Jay negotiated a remarkable deal with Britain.

Most importantly, the Treaty of Versailles specified that Britain would recognize the former colonies as “free Sovereign and independent States.” The treaty also recognized their land claims in the western territory and guaranteed fishing rights off the banks of Newfoundland. Britain even transferred its rights of navigation on the Mississippi (which had been secured from Spain in the Treaty of 1763) to the newly independent states. Spain was not obligated to recognize the transmission of this right, but securing the formal acknowledgment that Britain conveyed its claims would give the United States greater leverage in future negotiations with Spain.

Although some objected that the Treaty of Versailles represented a breach of trust with the French, most Americans hailed it as a triumph. More ominously, however, by removing the external threat of war, regional splits that had been temporarily suppressed by foreign dangers now came bubbling to the surface. Many feared that disunion would be the inevitable result of concluding the war.

General George Washington, after dramatically resigning his military commission, wrote a farewell address warning against “a spirit of disunion.” Washington was more than a war hero by this time. He was America’s greatest symbol of self-sacrifice and public spiritedness, and now he was calling on his countrymen to emulate his example. Their willingness to lay aside local prejudices and endow the Union with sufficient power would determine “whether the revolution must ultimately be considered as a blessing or a curse.”