America's Secular Church

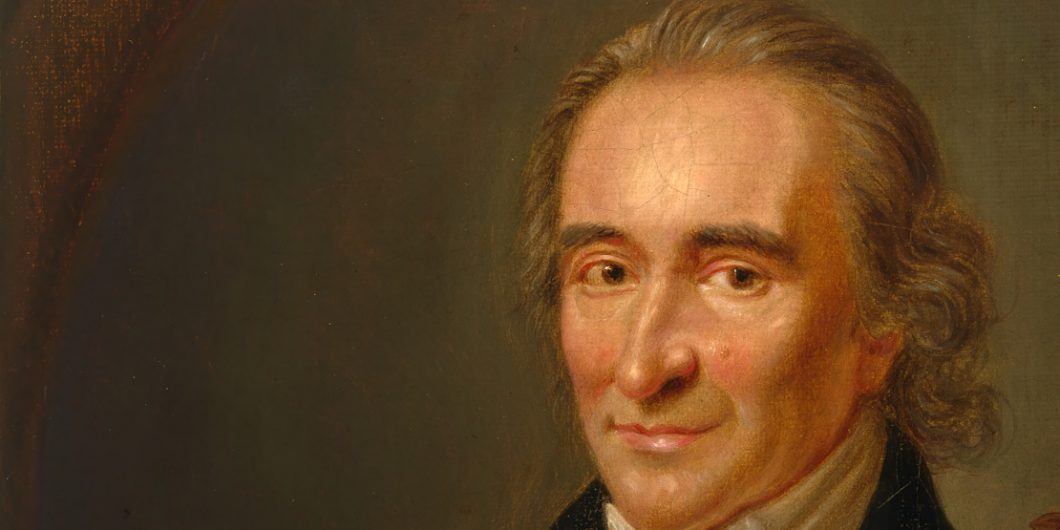

It is surprising to learn that Thomas Paine, the roving revolutionary and pamphleteer for American independence, was the patron saint of an eclectic assortment of nineteenth- and twentieth-century free-thinking, agnostic, atheistic, humanistic, and secular individuals and organizations who wanted not just for the old religions to wither and die but to found a new “religion of humanity, a church of humanity,” that would replace them. “The world is my country, to do good my religion” had written the founding father of American free thought, and a number of Americans followed in his footsteps.

In his intriguingly entitled The Church of Saint Thomas Paine, Leigh Eric Schmidt, a laurelled historian of American religion and culture at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, frames three finely crafted chapters—“Relics of the Secular Saint Thomas” (i. e., Thomas Paine), “Positivist Rites and Secular Funerals,” and “Churches of Humanity”—between an introductory chapter on “The Religion of Secularism” and an epilogue that looks “Beyond Secular Humanism.”

In the three core chapters of his study, Schmidt tells the fascinating stories of American secularists who sought “to honor their maligned heroes, to ritualize their [own] lives and memorialize their dead, and to create solidarity among themselves in their alienation from Christianity and the prevailing religious order.” In a cultural environment of often legally enforced biblical beliefs, they nurtured “imperial” dreams of the world-wide spread of their secular faith, while also more modestly striving for “minority rights” coequal with their believing fellow-citizens.

This hardy minority was out of step not only with the Christian majority, but also with “purist” secularists who criticized them as incoherently seeking to replace, rather than repudiate, old religious forms and rituals. Religion as such needed to be banished from the world, not just its superstitious forms. In his study, therefore, Schmidt also touches upon this intriguing intrasecularist debate. To do so requires him to broaden his perspective, as “local American voices [participated] in a multifaceted debate that had arisen repeatedly across Europe and North America since the Enlightenment and still resonates in the contemporary religious landscape.” Thus to the cast of American secularist figures such as Robert Ingersoll (1833-1899), Upton Sinclair (1878-1968), and A. D. Faupell, one must add foreigners such as the British freethinker George Jacob Holyoake (1817-1906), who coined the term “secularism,” and the French positivist thinker Auguste Comte (1798-1857), who laid out in extensive detail a “religion of Humanity” that proposed Mankind as the proper object of human reverence and devotion. Here is an underappreciated chapter in the history of intellectual exchanges between Europe and America.

At a meta-level, therefore, one could extract three broad intellectual attitudes involved in the story Schmidt tells (traditional biblical believers, religiously minded secularists, and purists). Within the two species of secularists, he presents a fascinating menagerie of individual characters. Together, ideal types and individuals help tell a story, and stories, of dramatic human and American significance. Given their stakes and significance, however, which include the truth of God, man, and the proper orientation of individual and social life, one has to regret that Schmidt doesn’t delve more deeply into the philosophical and theological issues that his figures engaged and decided for themselves. This may indicate the limits of the historian’s task as he understands it, or simply limits he chose to impose upon himself. In either case, I’m not sure they are justified, that is, just to his subjects or to the inquiring reader. The majority of the figures he limns aren’t quite fully human, their minds and hearts aren’t adequately plumbed. They have their secularist views and opinions. Period. With one or two exceptions, we’re not told how they came to them. We’re never given any criteria for evaluating them. Telling stories with verve—as Schmidt does—does not make up for not letting his subjects make their case for their views and positions, nor for not enabling the reader to judge their merits.

The same sort of inadequate treatment of vitally important subjects is found in his treatment of constitutional matters. With one exception, Schmidt declines to comment on the deeply problematic character and results of the Warren (1953-1969) and Burger (1969-1986) Courts’ religious jurisprudence. He passes by the important question of the legitimacy of excising religious belief, instruction, and practice from core institutions of our public life and tends to link their rulings to the protection of minorities, without subjecting them to real constitutional scrutiny. He would have benefited from reading Philip Hamburger and Thomas West. They explode the (Hugo) Blackian myth of the high wall of separation between religion and our public life and institutions. And if he had read David Lowenthal’s No Liberty for License, he would have encountered a closely-argued republican reading of the entire First Amendment that makes clear how hostile to the founding vision modern secular liberalism’s interpretation actually is.

Schmidt regularly contrasts the grandiose plans and hopes of the Paine-inspired, religiously minded secularists with their minuscule numbers and negligible cultural and political clout.

Therefore, the lesson he feels warranted to draw from the story he tells loses a good deal of its force. Schmidt regularly contrasts the grandiose plans and hopes of the Paine-inspired, religiously minded secularists with their minuscule numbers and negligible cultural and political clout. He uses this disproportion between ambition and capability to challenge their Christian opponents, especially those in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s who made “secular humanism” a bogeyman, ubiquitous and domineering. He wants to “expose the spectral fears and rhetorical excesses of their Christian critics.” In truth, it was “a convenient scapegoat” for Christians.

However, he doesn’t explore what it was a scapegoat for. In his classic work, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America (1992), the sociologist James Davison Hunter provided a plausible answer with his broader category of “Progressivism.” Progressivism was indeed a sworn enemy of transcendent religion and traditional moral norms, and it had increasing cultural and political clout from the late-nineteenth century onwards. A version of it informed the religious jurisprudence of the two aforementioned courts.

Of this quite manifest challenge to traditional belief and its public standing, there is not a word from Schmidt. To acknowledge it would have required him to present Christian believers as less narrow and benighted, more in tune with real currents and challenges to Christianity’s traditional role in public life. In general, the sympathy he displays toward the two sorts of secularists deserts him when it comes to their Christian opponents. They verge on cardboard figures. This allows him to ignore the greater tree line of judicial, cultural, and even “political secularism” by pointing out a few secular humanist bushes.

Remarkable for a book published in 2021, its emotional center resides in the cultural and political battles of the 60s through the 90s, especially the 80s. The falsehoods and indignities inflicted on Walter Mondale during the 1984 campaign are rebutted by Schmidt, while a hero of the book, William Henry Young, exhibited the proper “concern over the growing involvement of evangelicals in right-wing politics.” In contrast to Schmidt’s typical treatment of secularists, and in stark contrast to his treatment of their “Christian critics,” Young’s intellectual and spiritual itinerary and final position are laid out in considerable detail in five-plus pages of text (and one and a half of notes). He is thus given a prominence that arrests the reader.

In his “third and final ‘conversion experience,’” Young was struck by the utter mysteriousness of the cosmos and human existence. From this, he drew his version of Socrates’s “human wisdom,” “knowledge of one’s ignorance.” Unlike Socrates, however, he didn’t enter the agora and press on. “From that moment on, I was an Agnostic.” More like Candide than Socrates, he retired to his garden, a mountain retreat on the edge of the Sierra Nevada National Forest. From there he concocted a unique mélange of agnosticism and the “writings of Huxley, Ingersoll, and Russell,” along with “strands of Unitarian religious humanism and Quaker practice.” To all this, he added an evangelizing spirit, founding “the Society of Evangelical Agnostics” that lasted from 1975 to 1987. From Schmidt’s dotingly detailed treatment, the reader could reasonably infer admiration and even subtle advocacy.

For this reader, however, the portrait raises philosophical and theological questions. These start with Young’s characterization of God:

the realization struck me as a gentle theistic lightning bolt that if God wanted his creatures to have answers to the big questions about “Ultimate Reality,” the purpose of the universe, the meaning of life and death for man, etc., He would have provided more definite and convincing information.

Apparently, Young never read Pascal and Calvin on the human cognitive condition. These Christian thinkers would certainly contest his inference and its presuppositions. On the other hand, from a Socratic perspective, one would have to say that his decision for agnosticism was precipitous and dogmatic. Socrates is the eternal gadfly of self-satisfied agnosticism, as well as of cock-sure believers of various sorts. To all, he issues his challenge of “giving an account” (logon didonai). What I found most wanting in this book is that its author didn’t allow me to engage with its subjects on this fundamental human plane. Nor, for that matter, with the normative views of its author.