Having had my fun at the European Union’s expense, perhaps it’s time to move past Lufthansa jokes (although I do have a few more) and pay more serious attention to the EU and its federalism. There’s little room for American gloating or Schadenfreude: the ongoing EU disaster is hanging over our economy; and besides, our own federalism isn’t in such terrific shape, either. Read on to learn more.

“Arresting the Progress of the Evil”

Modern American constitutionalism, with its emphasis on executive power and judicial supremacy, obfuscates constitutional history. Because we have lost so much of that constitutional past, any explanation of a tradition that departs from contemporary norms now requires an act of historical recovery, of venturing into a different world with mentalities and beliefs far removed from today. Christian G. Fritz’s Monitoring American Federalism: The History of State Legislative Resistance makes a convincing case that no past constitutional practice has suffered more from contemporary modes than federalism. His exploration into the rich history of federalism in the Early Republic reveals how Americans believed the states should be active and significant players in shaping constitutional meaning. Fritz’s primary thesis is that interposition, the idea that states could intervene in constitutional questions, lay at the heart of this robust system of federalism and served as an “important venue to provide constitutional meaning and an assessment of the equilibrium of federalism.” In essence, interposition became a vital tool in sustaining the federalism established by the Constitution.

Fritz defines interposition as “a formal state protest against actions of the national government designed to focus public attention and generate interstate political pressure in an effort to reverse the national government’s alleged constitutional overreach.” Fritz wants readers to view interposition as a conversation starter, a method for the states to bring attention to or warn against federal actions. Interposition-as-conversation starter thus became a tool for the states. In the practical sense, the desire to preserve harmony between a federal government with ill-defined enumerations of power and state governments, each with their own spheres of responsibility, meant a never-ending contest to define and monitor the boundaries of federalism and national power. Fritz’s definition, moreover, allows him to separate interposition from nullification, which he considers a “distorted” understanding of interposition. For reasons that Fritz elaborates in the book’s second half, nullification became the understanding of interposition in the antebellum period.

What may surprise readers is that Fritz locates the origins of interposition in Alexander Hamilton and James Madison’s writings in The Federalist. While neither championed the states in 1787, they realized that the Anti-Federalists’ fears of consolidation required a response that demonstrated the continued necessity of the states. Federalist essays #6, #28, #84, and #85 (Hamilton) and #44, #46, #52, and #55 (Madison) explained that necessity. At the same time, the two “architects of interposition” established the three tenets of interposition. First, state legislatures served as a sentinel against consolidation—they were the guards on the watchtower. Second, these state legislatures could sound the alarm on potential federal overreach. Third, state legislatures could create interstate movements to “invite discussion and renewed consideration” of federal actions and perhaps correct federal aggrandizement through a potential range of actions.

Just what these possible actions might be remained frustratingly unclear. Fritz admits that Madison and Hamilton implied that the right of revolution remained on the table. This lack of clarity on Publius’ part left interposition “somewhat muddled and potentially dangerous from the beginning.” Despite the lurking danger, The Federalists’ definition of interposition as a debate starter emerged quickly in the first years under the Constitution. From Alexander Hamilton’s financial program and Chisholm v. Georgia to the Eleventh Amendment and the Jay Treaty, states relied upon interposition throughout the early 1790s to debate and shape constitutional interpretation and meaning.

In the nineteenth century, however, Publius’ understanding of interposition became increasingly “distorted” and “evolved” into the “problematic” and “dangerous” idea of nullification, or the idea that an individual state could veto federal law. As explained and defended by the boogie-man of the early republic, John C. Calhoun, nullification not only transformed interposition but planted the seeds of secession and war. Although Monitoring American Federalism attributes this transformation to the increasing sectional debate over slavery, Fritz’s analysis does not consider either interposition or nullification as inherently racist or designed to maintain the “slave power.” His detailed examination of Northern states’ resistance to the Fugitive Slave Laws of 1793 and 1850, as well as his discussions of Prigg vs. Pennsylvania and Ableman v. Booth, reveal that, while slavery became the wedge that separated the sections, both North and South contributed to the bastardizing of interposition-as-conversation starter. For Fritz, the slide towards nullification and civil war becomes a constitutional tragedy.

Interposition offered a feasible solution to what would otherwise be a slippery slope towards tyranny.

The first act of this tragedy, where interposition began its metamorphosis into nullification, occurred with the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798. The lengthy discussion on those seminal papers is the most important chapter of the book. Fritz notes that while scholars consider the resolutions as providing the fuel to ignite Calhoun’s theory of nullification thirty years later, the Resolutions are better understood as reflecting the “earlier pattern of interposition that traced its roots to The Federalist.” Nonetheless, Jefferson’s draft (rather than the final version adopted by the Kentucky legislature) contained what Fritz repeatedly calls “problematic language.”

First, Jefferson embraced the compact theory of the union, which suggested that “the national government served as an agent acting on behalf of certain co-partners, essentially exercising a power of attorney.” The contractual nature of the Constitution meant that the government it created could not define the limits of its powers; only the parties that agreed to the contract could do so. Fritz is also troubled by the implication in the Eighth Resolve that, since the federal government exercised powers not delegated to it, the state (to quote Jefferson) had a “natural right, in cases not within the compact . . . to nullify of their own authority all assumptions of power by others within their limits.” Fritz’s frustration continues, as Jefferson wanted interposition to mean more than just sounding the alarm; he believed that “individual states” (Fritz’s emphasis) had a natural right to challenge “by force” (Fritz’s emphasis) those laws the state deemed unconstitutional. This “problematic language” eventually created the “more troubling interpretation” of early American constitutionalism, the doctrine of secession.

Whereas Jefferson’s draft failed to distinguish the “ordinary tool” of interposition from a state’s natural right to revolt, Madison’s Virginia Resolution, by contrast, initially followed the typical route of sounding the alarm that interposition had taken since Madison supposedly helped establish the idea in The Federalist. Yet, it too “introduced its own confusion” with disastrous results for the future. For Fritz, Madison’s great linguistic mistake occurred in the Third Resolution. For readers to understand Fritz’s argument, I quote the entirety of that Resolution:

That this Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact to which the states are parties; as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting that compact; as no farther valid than they are authorised by the grants enumerated in that compact, and that in case of a deliberate, palpable and dangerous exercise of other powers not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties there-to have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.

Fritz argues that since 1800, practically everyone has overlooked two critical aspects of this Resolve, leading to a fundamental misunderstanding of Madison’s meaning and intention. First, Madison’s use of the plural in reference to the “states are parties” to the Constitution meant resistance to federal action required a collective action of the states. This collectiveness contrasts with the singular natural right of individual states claimed by Jefferson. Since the collective actions and “not each state individually” ratified the Constitution, Virginia alone could not resist federal actions.

More importantly, however, is Fritz’s claim that the Third Resolution did not reference interposition-as-conversation starter. Critical to Fritz’s claim is Madison’s explanation of the Third Resolution in Report of 1800, in which he asserted that the word “state” could refer to one of three things: the territory of a political society, the government of that political society, or the political society in its “sovereign capacity.” Madison noted that

in the present instance whatever different constructions of the term “States,” in the resolution may have been entertained, all will at least concur in that last mentioned [e.g., the people in their sovereign capacity]; because in that sense, the Constitution was submitted to the “States”: In that sense the “States” ratified it; and in that sense of the term “States,” they are consequently parties to the compact from which the powers of the Federal Government result.

To Fritz, Madison’s use of “States” to refer to popular sovereignty suggested that the “legislative interposition in the Third resolution” was not referring to interposition “despite the fact he used the word ‘interposition.'” Instead, Madison’s use of the term meant “what authority as a matter of constitutional theory resided in the parties who represented the underlying sovereignty of the Constitution and what action they might take” (Fritz’s emphasis). In other words, Madison’s Third Resolution did not propose a practical solution to the Alien and Sedition Act; it offered nothing more than theoretical argument defending the right of the sovereign people of the states to take matters into their own hands as an avenue of last resort. Fritz attributes the persistent misunderstanding of the Resolution’s theoretical foundation to Madison’s “need to articulate the theoretical implications of the Constitution.” The failure to “convey the idea that the Third resolution referred [to] the theoretical right of how that sovereign might interpose” (Fritz’s emphasis) rests squarely on the shoulders of the diminutive Virginian.

Although Fritz offers a unique and fresh reading of the Virginia Resolution, his position that Madison acted too theoretical for his (and the Union’s) own good is hard to reconcile with the Resolution’s plain language. There is no evidence that Madison considered the Third Resolve as solely an articulation of political theory. Fritz has to read that interpretation into the document. Madison’s description of “deliberate, palpable, and dangerous” provided a practical constitutional threshold that had to be met before triggering interposition. Upon reaching this threshold, as the Alien and Sedition Acts did, interposition offered a feasible solution to what would otherwise be a slippery slope toward tyranny. This fear of a slippery slope explains why Madison devoted the Fourth and Fifth Resolves of the Virginia Resolution to attacking what he called the “forced constructions” of the Constitution. If left unchecked, those constructions would “consolidate the states by degrees into one sovereignty.”

Nor did Madison indicate that he believed interposition required a collective action of the states. Both legislatures sent their resolutions to the other states. But this hoped-for collaboration does not hint at or suggest that Madison’s use of the plural “states” was in any way an exclusive appeal to collective action. The fact that individual state legislatures took action suggests that interposition was not inherently a collective act. This is not as flippant as it sounds. American history, from the Stamp Act Congress of 1765 and Continental Congress of 1774 to the 1814 Hartford Convention and 1850 Nashville Convention, all demonstrate that Americans considered collective actions as a possible means of achieving political and constitutional results. None of that history, however, suggests that interposition must be and should be defined exclusively as a collective act.

The Revolutionary and Confederation periods are replete with examples of state interposition.

Furthermore, if Madison believed interposition was only a collective act, it does not explain his claim in the second half of that resolve that the states are “duty bound to interpose” to “arrest the evil.” As individual members of a compact (a phrase Madison also used), each state, acting individually, must do what it can to stop tyrannical actions. Those individual and duty-bound acts of resistance could form a compounded collective action, but it does not mean that without collective action, those states who wanted to resist were left to the mercy of those who did not. That defeats the very purpose of the states individually joining the union. Madison’s language in the Third Resolve is of particular importance here. He states that, by interposing, the states would be “maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.” These limits, authorities, rights, and liberties vary from state to state; they are not universal. Hence, even if each of the several states did engage in interposition, each one did so within its own jurisdiction. Madison also noted in the Seventh Resolve that Virginia was “appeal[ing] to the like dispositions of the other States” and that “the necessary and proper measures will be taken by each, for cooperating with this State.” Nothing in this language suggests collective action is the only legitimate method of interposition. If anything, “taken by each, for cooperating with the state” seems to be a blatant statement that the individual states should act on their own accord first, and only then could it turn into a compounded action.

Fritz’s explanation of the Third Resolution as an expression of popular sovereignty is also frustrating. Fritz is correct that Madison believed the people of the several states ratified the Constitution; he maintained that position as early as Federalist #39 and never relented. Still, there is nothing in Madison’s reference to the people “in their highest sovereign capacity” in the Report of 1800 to suggest that the state governments, reflecting the sovereignty of their people, could not act on their behalf. In essence, when the state government(s) interposed on constitutional issues, it did so in the name of the people of the state. It does not make sense why, if Madison believed the state governments could not interpose in the name of the people of the state, he would suggest in The Federalist, the Virginia Resolutions, and Report of 1800 that states could and should interpose when necessary.

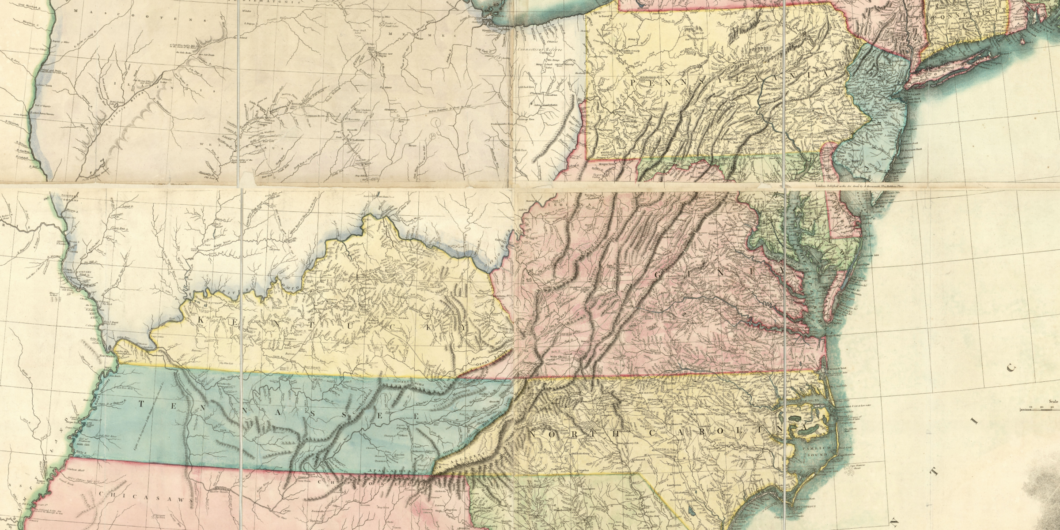

Misreading Madison’s Virginia Resolution is not the only instance of questionable interpretations or bad history. His is a dual belief that federalism first emerged with the 1787 Constitution and that Publius—Hamilton and Madison—invented interposition is historically inaccurate. He ignores the entirety of the American constitutional development before 1787. As Jack P. Greene, David Hendrickson, and others, have demonstrated, federalism’s roots were buried in the colonial era, reaffirmed with the Articles of Confederation, and maintained with the Constitution. Each of these developments certainly brought variations and modifications to how Americans understood federalism, but what is clear is that by 1787, a long tradition and experience with federalism and its division of powers had already existed. The Framers of the Constitution did not create federalism ex nihilo.

This means, too, that Americans had prior experience with policing the boundaries of centralized power. The Revolutionary and Confederation periods are replete with examples of state interposition. I will offer two notable examples. In 1777, the Continental Congress debated whether Congress or the states were responsible for prosecuting desertion. John Adams noted that Congress’ power extended to only those elements contained in the Articles of War (this was before the adoption of the Articles of Confederation) and that “it was the Duty of the states to Interpose whenever the Question arose” if the deserter was a soldier or citizen. Adams’ use of duty with interposition is no different than Madison’s twenty-one years later in the Virginia Resolution. The most forceful expression of state interposition in this era came from the pen of Virginia’s Merriweather Smith and his attack on the Loyalist-friendly Articles IV and V of the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Believing those Articles violated the rights of the states to enact laws and rights of Virginians (and citizens of the other states), Smith claimed

the principle of the revolution applies equally; and congress have no more authority in the one case than in the other. It is the duty of the individuals to defend themselves, and it is the duty of the state to preserve its authority and dignity of its laws, and to save its citizens from the ruin which threatens them. Wisdom and firmness in the legislature will be a sure state guard to the people (emphasis in the original).

Once again, notice the connection between the state’s duty to protect itself and its citizens from perceived overreach. Nothing here separates Smith’s remarks from Adams six years earlier or used by Jefferson and Madison fifteen years later. All of this is to state that Fritz is wrong to claim Hamilton or Madison invented interposition. They may have endorsed it in The Federalist, but they, too, were drawing upon an already well-established idea.

Finally, Fritz’s desire to create a gulf between interposition and nullification also ignores historical precedent. He is correct to point to the interposition-as-conversation starter as an element of the idea, but that was not its only function. Fritz does not explore or attempt to explain what happens if an interposition occurs, but the federal government ignores the conversation and continues unabated. Are the states—collectively or individually—helpless against a perceived unconstitutional or blatantly tyrannical action? This is where nullification plays a critical role. Rather than being intellectually and constitutionally separate from interposition, nullification was the next step in guarding the boundaries of federalism. In essence, nullification is interposition-as-action. Nor was nullification a constitutional innovation in the 1830s; its pedigree began before the Constitution, too. Throughout the Confederation period, especially in the debates over the 1783 treaty, Smith’s call for “firmness” in the legislatures was met throughout the states with petitions by numerous groups calling for the states not to enforce those provisions. In fact, during the 1780s, states enacted legislation that purposefully contradicted the Treaty’s terms. That is not interposition-as-conversation starter; that is nullification.

While Fritz’s history of interposition is commendable, it does not go far enough in its recovery. In essence, Monitoring American Federalism creates a false dichotomy in which the Early Republic and its interposition-as-conversation starter emerged as the ideal standard, only to be sullied and broken by nullification in the antebellum period. This dichotomy only occurs because Fritz ignores the long history of federalism, interposition, and nullification before the Constitution. Had Fritz focused on that early history, he would have seen that the constitutionalism of the first century of American history was not one of complete disruption but instead of surprising continuity.