Conservative Liberalism's Many Lives

Facts persist in defying the purported wisdom of history’s march toward its ever-elusive end. Yet many mortals caught on the wrong side of Eden won’t let go. The notion of a capital-P Progressive history—credited by Marxists to materialist forces that oppressed masses led by enlightened vanguards were supposed to unleash—continues to elicit allegiance among the intelligentsia and the gullible. This is despite catastrophes caused by invoking it, which a modicum of common sense could, and did, anticipate. The rational skeptic who warns against repeating the ever-recurring madness is dismissed as an outlying Cassandra, or worse. Refusing to be intimidated by fellow academics takes unusual equanimity, stubbornness, and indifference to opprobrium. These happened to be just the qualities for which a certain Austrian-born economist of Czech and Hungarian origin was loved and admired by his grateful students at the University of Chicago.

Professor Hayek had predicted the terrible fate that would befall the world as early as 1933, long before the full enormity would be unveiled. The war had not yet ended when his most widely read book, The Road to Serfdom, was published in England on March 10, 1944. One of his most devoted followers, the too-little-known Hannes Gissurarson, would not be born for another 13 years. A popular professor at the University of Iceland’s Social Research Institute until his retirement in 2023, Gissurarson has recently published a two-volume study with a deceptively simple title: Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers. Acknowledging Hayek’s central role in articulating this philosophy, Gissurarson shows how multiple perspectives enhance its intellectual vitality. It deserves a wide readership.

But Hayek’s professional road, unsurprisingly, would not be smooth. Even most intellectuals attracted to his ideas were unconvinced that capitalism and freedom were inseparable—his central thesis. He arrived in Chicago in the 1950s and was hired by the interdisciplinary Committee on Social Thought (CST), not the Economics Department. Two decades later, then-CST chairman John Nef explained why: “[T]he economists had opposed his appointment in Economics for years before largely because they regarded his Road to Serfdom as too popular a work for a respectable scholar to perpetuate.” Runaway international bestsellers don’t look good on a resume. CST was then, and amazingly still is, an exemplary academic dinosaur.

Even many intellectuals who agreed with most of Hayek’s conclusions still clung to the notion that a little state coercion was justified, provided it was well-intentioned. Some social democrats, democratic socialists, and even neo-Marxists, persisted in believing that a kind of benign socialism might be compatible with individual freedom. For example, at a large conference organized in 1955 by the US-backed (as it later transpired, CIA-funded) Congress for Cultural Freedom held in Milan, Hayek stood practically alone. And so he would remain for nearly two decades.

Until 1974, when to everyone’s surprise but especially his own, the world learned that Hayek was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics. The following year, Margaret Thatcher held up one of his books at a meeting of the Conservative Research Department with the words: “This is what we believe.” After becoming Prime Minister in 1979, she told him: “I am very proud to have learnt so much from you over the past few years.” Ronald Reagan, elected in 1980, similarly expressed great admiration for his books and ideas.

But the most dramatic revelation came only after the collapse of the Soviet Empire—the one totalitarian system that lasted long enough to serve as a horrific confirmation of Hayek’s predictions. It turned out that his most devoted followers all along had had most to lose by even reading him. By the time America bestowed its Medal of Freedom upon him in November 1991, democratic leaders of the newly independent Eastern bloc countries were able to reveal clandestine translations of The Road to Serfdom, which they had studied at enormous personal risk. The 92-year-old Hayek was overwhelmed. But refusing to take any credit himself, he declared the end of communism as simply “the ultimate victory of our side in the long dispute of the principles of the free market.”

Those principles had also resonated in, of all places, far-off Iceland. In October 1984, 21-year-old Hannes Gissurarson and a friend decided to operate an illegal radio station to protest the government’s monopoly on broadcasting. After the police closed it, also slapping a hefty fine on the young dissenters, the Independence Party took on the cause. The following year, the monopoly was abolished. Meanwhile, Gissurarson had completed his doctoral dissertation at Oxford University, titled “Hayek’s Conservative Liberalism,” published in 1987 in Brussels. The label symbolized the fusion of apparent opposites that are, in fact, complementary. He thus ingeniously replaced a polarizing dialectic, bound to sow discord, with a term whose sober nuance suggests theoretical clarity tempered by prudence.

In the introduction, Gissurarson explains that what had attracted him to Hayek’s political theory was its coherence: “From the same premises, [namely] man’s inevitable ignorance, and the existence of the extended society, social conservatism and economic liberalism can both be seen to follow.” That coherence stems from the practical dimension of those premises coupled with a deep “commitment to a concrete social and historical reality, the liberal civilization of the West.”

In subsequent chapters, Gissurarson assesses challenges to Hayek by political theorists from both conservative and liberal camps who nonetheless shared a hostility to totalitarianism, and ultimately concludes that he is an uncommonly unifying figure. He commends Hayek to both camps, arguing that not only do “conservatives have much to learn” from the master; indeed, “Hayek’s fellow liberals perhaps even more.” Consistently defending human individuality as the fruit, not the foe, of tradition, Hayek was most concerned about collectivist/progressive illusions. Taking the wrong turn on a road promising nirvana but in fact leading to serfdom was not only unwise, it could be lethal.

Gissurarson was all in. The college student who started as an illegal radio station operator had found his mission: defending the free market and Western civilization. After joining, in 1984, the prestigious Mont Pelerin Society that Hayek founded in 1947 with help from Milton Friedman and Aaron Director, among others, Gissurarson served on its board of directors from 1998 to 2004. He also joined the board of Iceland’s Central Bank from 2001 to 2009. His anthology on conservative liberalism represents a major contribution to the contemporary war of ideas.

At once political theory, autobiography, and personal commentary on economic policies, the work is truly unique. The featured thinkers span the continent: of the twenty-four, seven are British, Scottish, or Irish, five are American, five are German-speaking, four are French, one is Italian, another is a Swede, and last but chronologically first, one Icelander. Their philosophy predates modernity. Gissurarson describes conservative liberalism as “a tradition which can be traced back to medieval ideas about government by consent,” tracing it even before the influential Catholic theologian Thomas Aquinas to the incomparable, if virtually unknown, Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241).

Hayek was always loath to relinquish “liberty” to its opponents who had brazenly appropriated the word.

Descended from Norwegian kings, educated in Germany, this erudite nobleman who became Iceland’s Lawspeaker at a very young age, was an accomplished writer who had captured in his epic sagas Iceland’s legendary freedom “from the assaults of kings and criminals.” Centuries before the Whigs in Britain, writes Gissurarson, Sturluson articulated the principle that

government should be by consent, not by the grace of God; that there was in place an implicit social contract between the people and the sovereign and that the people could depose the sovereign if he violated that contract; and that man could be defined not only by some general category, but had to be conceived of also as an individual who had acquired the ability and will to make his or her own choices.

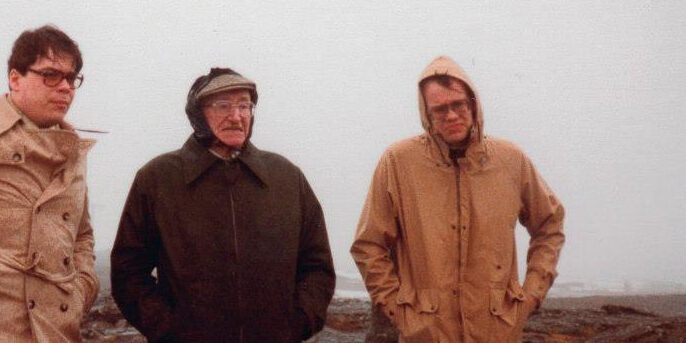

Hayek was to learn all about Sturluson on his delightful visit to this small nation of unspeakable beauty. He had been invited by Gissurarson who, together with a few friends—all Oxonians—founded the Icelandic Libertarian Association on Hayek’s 80th birthday, on May 8, 1979. He graciously accepted and arrived the following April. They all got along famously; but when asked whether he would mind if they founded a Hayek Society at Oxford, he responded: “I am of course quite happy that young people are interested in my ideas and arguments. It is a welcome change. But you have to promise me one thing. I have noticed that the Marxists are much worse than Marx and that the Keynesians are much worse than Keynes. Therefore you have to promise me that you do not become Hayekians. You have to maintain a critical attitude and think independently.”

Hayek’s modesty was a personal trait. But it was also fundamental to his belief that every individual has a perspective on reality, which should not be swayed by groupthink or any other anti-rational considerations. No one should presume to decide for another—on both moral and epistemological grounds. Besides, he trusted most people’s willingness to build communities for mutual benefit. Loathe to attribute bad intentions to those with whom he disagreed, he firmly believed that socialism reflected an intellectual error rather than disagreement about ends. He advised his young Oxonian disciples that a debate between liberals and socialists would prove helpful in bringing this out.

But reason must be supplemented by virtue, for liberty requires social restraint. Liberty can only survive under the law, which includes society’s moral code. He then recalled the time he met Pope John Paul II some years earlier. The prelate had been pleased when Hayek “suggested not to call principles which could not be proved and had to be taken on authority, such as religious dogmas, ‘superstitions,’ using instead the term ‘symbolic truths’ about them.” Symbolic truths, for Hayek, are not only on par with empirical and mathematical truths but prior.

As Hayek explained in Law, Legislation and Liberty (1971), invoking both the Scottish empiricist David Hume and the German idealist Immanuel Kant, symbolic truths and the values they embody are “guiding conditions of all rational construction” and thought. Science itself “rests on a system of values which cannot be scientifically proven.” This does not mean that knowledge and truth are built on quicksand. It does imply that values matter, and paramount among them is the freedom of each individual to pursue what he perceives to be to his own and his community’s benefit.

This is required by the immeasurable complexity of understanding the world and man’s place in it. Ultimately, the common good cannot be deliberately designed—the impossibility is both conceptual and, above all, moral. Society therefore can thrive “only by consistently adhering to certain principles throughout a process of evolution.” Rather than explicitly articulated in rules, such “principles are often more effective guides for action when they appear as no more than an unreasoned prejudice, a general feeling that certain things simply ‘are not done.’” If this is reminiscent of Edmund Burke, it should be, for in his 1960 essay “Why I am Not a Conservative,” Hayek included Burke alongside Lord Acton, Thomas Babington Macaulay, and William E. Gladstone as the three greatest British liberals.

Nevertheless, Hayek refused to adopt the “conservative” label outright. Not unlike Milton Friedman and other defenders of Adam Smith’s “system of natural liberty,” Hayek was always loath to relinquish “liberty” to its opponents who had brazenly appropriated the word. He would have adopted “Whiggism” were it not extinct. And while he agreed with many, if not most conservatives, he found too many unduly prone to a “nostalgic longing for the past or a romantic admiration for what has been.” Besides, having described himself as a liberal all his life, he wasn’t about to stop. As Gissurarson argues in his dissertation, the difference between the conservative mindset and Hayek’s was that the latter’s approach “leads to a theory of progress.”

His was not an inevitable or irreversible, let alone utopian, view of progress. “It is a belief, rather, in the possibility and desirability of progress, where progress is the extension of our practical and moral vision, or the enlargement of our range of goals, values, and opportunities,” writes Gissurarson. Moreover, “it is the conviction that liberty can, and ought to be, extended to all human beings.” How better to express the spirit behind the American Declaration of Independence, the ultimate expression of conservative liberalism avant la lettre [French for “letter”]—to say nothing of the sacred commandment from Genesis.

Hayek would undoubtedly be enormously pleased by Gissurarson’s collection of like-minded thinkers. Far from monolithic, they offer “various kinds of arguments for their positions, from divine command, human reason, social utility, natural evolution, moral intuition, and common consent,” which Hayek would find intellectually invigorating. At the same time, “these positions are all in the end based on a choice, which is a commitment to, indeed a celebration of, Judeo-Christian Western civilization.” Free choice is the prerogative of humans who are endowed by their Creator with the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness that is impossible without private property.

The young Oxonian from Iceland has proved beyond doubt to have been worthy of Hayek’s friendship and trust. The closing statement of his remarkable book captures it best: “Perhaps the best, albeit somewhat metaphysical, way of describing conservative liberalism is as the self-consciousness of Western civilisation.” The venerable Viennese master could not have said it better.