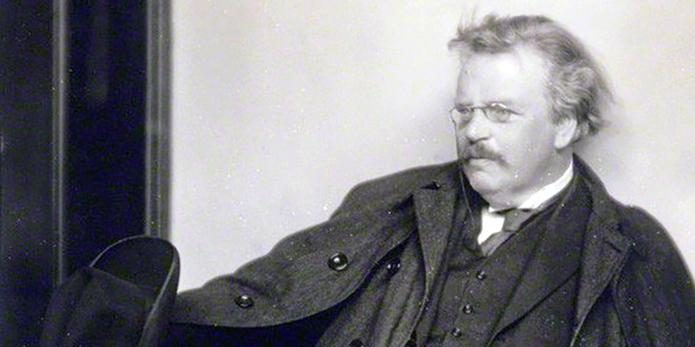

Franz Boas, G.K. Chesterton, and Pope Pius XI all criticized lumping people together into categories according to biology.

Missing Chesterton’s Politics

“It is a good sign in a nation when things are done badly. It shows that all the people are doing them. And it is bad sign in a nation when such things are done very well, for it shows that only a few experts and eccentrics are doing them, and that the nation is merely looking on.”

—G. K. Chesterton

Alex Salter was the right person to write a book about distributism. He is well-known as a serious economist, committed Orthodox Christian, and generous interlocutor. Unlike most other economists, he really loves the distributist thinkers (especially Chesterton), which makes him eager to both correct and preserve their legacy. Ubi amor, ibi oculus.

The core thesis of The Political Economy of Distributism is that even though Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton made some basic economic (and historical) errors, their insights about political economy remain worthy of consideration. Salter takes great care to distinguish economics—which is a science with its own set of natural laws—from political economy—which is the art of building a good society. The primary claim of distributists that is worth “taking seriously” (to use Salter’s favorite turn of phrase) is that property must be widely distributed if true liberty is to be enjoyed. He holds up Wilhelm Röpke as a model for distributist thinkers and economists alike, as one who understood price theory while still being committed to upholding human dignity, the value of work, and family life. The book concludes by reflecting on ways to move forward with our inheritance from distributists, suggesting both a progressive research program and practical applications, such as the movement of common good capitalism.

Here is where Salter and I part ways. He makes the claim that even though distributist thinkers harbored deeply mistaken ideas about the way economies work, they were still correct when weighing in on certain issues of political economy. Röpke becomes the hero in this story, since he was a trained economist whose Christian humanist viewpoint still led him to propose policy solutions similar to those endorsed by Belloc and Chesterton. Amongst these are redistributing income more equally, dismantling large-scale industries, supporting small agriculture and artisanal enterprises, cushioning losses in declining industries, mandating a just wage when losses may be absorbed, and perhaps even discouraging specialization and international trade. Unlike Belloc and Chesterton, Röpke acknowledges that these policies would reduce material prosperity, but he judges that the benefits of a “humane society” are well worth the costs.

But this story is surely incomplete. In order to think prudently about matters of political economy, an understanding of economics paired with Christian humanism is not enough. One must at least understand the way that politics works as well. Interestingly, I think that Chesterton understood the real world of politics better than nearly all of his followers, and that his intuition about the dangers of interventionism and expert rule is likely why Salter, myself, and other notable economists have always felt at home in his pages.

The central claim of this review is that Chesterton’s politics are strangely missing from the tradition of distributism. In fact, Chesterton may even be fairly read as a prophet of “public choice”—the field of economics that analyzes the incentives of voters, lobbyists, and politicians. After summarizing the obvious economic errors of distributism, I want to use Chesterton’s own words to caution us before accepting the policy recommendations that his modern followers often put forward. Finally, it is worth reflecting more deeply on the problems and promise of using the notion of the common good as a north star for political economy.

The Economic Errors of Distributism

The Political Economy of Distributism begins by thoroughly documenting the economic errors of distributism as it is found in the foundational writings of Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton. Although this is referred to as the “minor claim” of the book, I view it as the central contribution. A few major themes are summarized below, but the reader is well-advised to read the full book chapters since Salter does a brilliant job of documenting exactly where distributist thinkers take a turn away from what economists understand to be true of market processes.

Modern distributist thought is currently being rebranded as “localism.” While this cleverly avoids the original term’s association with redistribution, it also has the benefit of flagging its economic errors. At the heart of distributist thought is the idea that life was better when centers of production were closer to the home and enterprises were smaller. However, the dream of turning the whole world, or even just the West, back to the life of medieval farmers (or post-WWII suburban America) must clash with the reality that everyday people would have to give up a lot. A lot of wealth, to start. A lot of health, too. Perhaps that’s fine. There is more to this world than wealth and health. But we must ask: how many people could the global economy feed if society was organized in this way? The answer is certainly not 7.9 billion. There is a reason our ancestors chose to forgo small family business production—they saw that the extension of the market and division of labor gave better lives to their children. Like it or not, big corporations like Walmart are to thank for reducing food insecurity amongst low and middle-income households. Appreciating the aesthetic and healthy options of a local farmer’s market or choosing a simple lifestyle for our families shouldn’t preclude us from acknowledging the unique blessings of global markets.

Another pervasive error that is unfortunately woven throughout distributist thought is the view that capitalism pits “labor” against “capital.” Capital is the term economists use to refer to the great variety of assets that yield income or other useful outputs over time—such as hammers, garden plots, computers, and steel plants. However, there is not so much competition between capital and labor as between types of capital and types of labor, which are substitutes for one another. I venture to claim, as does Salter, that what distributists are really concerned about is the degree of competition in a given industry. The good news is that economic research has identified a simple way for the state to make markets more competitive: avoid artificial barriers to small businesses and entrepreneurs entering an industry (e.g., occupational licensing or huge regulatory burdens) and limit restrictions on the mobility of resources and workers.

Pick the economic system of any era, then check the number of mouths it could (barely) feed. If one is willing to take the former, one better be ready to accept the latter.

Modern societies have very serious problems. Belloc, Chesterton, and their intellectual grandchildren are right about that. But serious problems require serious thought, and there is no thinking seriously about social issues without also searching for the unintended consequences of proposed policy solutions. Belloc was no Stalin and Chesterton no Mao, and if they knew that their dreams might have nightmarish consequences, I doubt they’d support them. But their consequences would be nightmarish. Pick the economic system of any era, then check the number of mouths it could (barely) feed. If one is willing to take the former, one better be ready to accept the latter.

Chesterton’s Politics

There is undoubtedly a difference between the science of economics and the art of political economy. However, the art of political economy requires not only a solid grasp of economics but of politics as well. While the distributist thinkers lacked an understanding of economic processes, Röpke and his followers seem to lack a realistic view of political processes. Salter does not consider himself part of this tradition—he notes that his “politics and economics are decidedly (classical) liberal”—yet he puts more faith in Röpke than I do. Luckily, we need not go far since Chesterton provides an ample dose of such prudence applied to politics (albeit in a characteristically flamboyant manner!). In particular, his writings contain three major observations: 1) politicians are rarely punished for their mistakes, 2) politics and religion are often in competition, and 3) rash policymaking can trample the accumulated traditional wisdom from centuries of trial and error.

Let’s begin with a quip that is quintessentially Chesterton: “It is terrible to contemplate how few politicians are hanged.” Unlike the disciplining profit and loss signals of the market, policy mistakes may not wreak havoc until well after the politician responsible is out of office. Perhaps the clearest example of this is the irresponsibly large government debt. Knowing it will gain votes, politicians face an incentive to promote large spending programs—from college loan forgiveness to economic protectionism—that benefit current recipients at a large cost to future generations. A thoroughly Chestertonian take on modern American politics would reject such exploitation of the voiceless unborn and focus on reforming political institutions so that political actors have more skin in the game.

Chesterton was also aware that politics can easily become a substitute for religion: “Once abolish the God, and the government becomes the God.” Consider care of the elderly, which comes up in the Bible numerous times as an obligation of children towards their parents and of churches toward their members. In response to the Great Depression, the Social Security system (the most redistributive program in the United States) began to provide the elderly with a regular income, given that they paid into the system during their working years. A hundred years later, elderly care has become bureaucratic, medicalized, and some countries have even started to promote euthanasia as their costs rise with an aging population. This is a general case of what is sometimes referred to in the economic literature as the “crowding-out” effect of political programs on civil society. When did the problem begin? With laws permitting euthanasia? Or perhaps further back, with political programs relieving children and churches of their obligations?

Finally, Chesterton understood the societal value of tradition, or as he cleverly referred to it, the “democracy of the dead.” Deep wisdom emerges from the trial and error of past generations, and it is a fool’s errand to erase such customs in pursuit of a drastically different society. Moreover, traditions cannot be imposed top-down (e.g., exporting democracy) but must grow organically from repeated interactions within a specific context. The delicate interplay between custom and law, or informal and formal institutions as economists refer to it, is likely why Catholic Social Teaching does not set forth one specific model beyond a broadly-defined “market economy” (the Church explicitly condemns socialism). The lengthy passage known as Chesterton’s fence, a favorite of policy wonks, drives home the point. Chestertonian political prudence can be summarized as such: “All government is an ugly necessity.”

Pursuing the Common Good

In his concluding chapter, Salter quotes this well-loved verse: “They shall all sit under their own vines and under their own fig trees, and no one shall make them afraid” (Micah 4:4). Pursing the common good—defined by Pope John XXIII as “the sum total of social conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfilment more fully and more easily”—is certainly a worthy endeavor. My primary dispute with distributists is not with their ends, but rather with their choice of means. Note the lines preceding Micah 4:4: “For out of Zion shall go forth instruction, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. He shall judge between many peoples and shall arbitrate between strong nations far away.” The power that achieves a good society is not mainly political but spiritual—“batter my heart, three-person’d God.” Ultimately, we must take a constrained view of fallen human nature and not ask of our political or economic institutions for the peace which this world cannot give.

Salter has accomplished something great by engaging seriously with distributist thought and tracing its effects to our current era. His book comes at an opportune time, as the “new-Right” is increasingly interested in thinking about pro-small business, pro-worker, and pro-family policy. While Salter rightly acknowledges the economic errors of Belloc and Chesterton and points to Röpke as a more discerning economic thinker, I would point Röpke back to Chesterton as the better political thinker. But perhaps this is all beside the point. The most important takeaway of this book is that if we truly love our (historical) friends, we should be eager to correct their errors with love and truth.