Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's warning about the great ideological Lie is a clarion call for the West to recover its civic pride and self-respect.

On "Liberal" as a Merit Badge

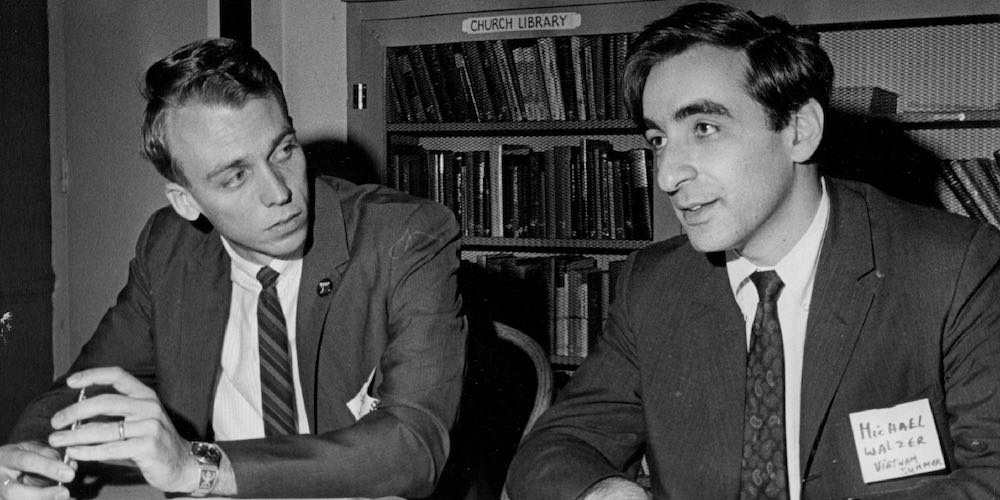

Michael Walzer’s The Struggle for a Decent Politics: On “Liberal” as an Adjective is avowedly not a tightly-argued work of political philosophy. “There is nothing systematic here,” announces Walzer in his preface. He developed the book out of an essay called “What it Means to Be a Liberal,” written in 2020 for Dissent (a magazine he co-edited for over 30 years). This extended version gives off the atmosphere of a companionable after-dinner reminiscence from a venerable movement leftist at the end of a long career.

Walzer wrote this slim reflection under strict COVID lockdown, using only those books he had to hand for reference. The result is discursive, readable, even occasionally charming. As a distinguished professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study, Walzer has a breezy facility with his subject matter. As a prolific author of learned volumes on a wide range of subjects, he has little to prove in the way of academic bona fides. So it would be petty and obtuse to insist on strict philosophical rigor from a book like this. All the same, I have some questions.

The first one is this: what can’t a liberal tolerate? The adjective “liberal,” as referred to in the subtitle, modifies the nouns to which it is attached—nouns like “democrat,” “socialist,” and “nationalist.” According to Walzer, the best version of any philosophy is one that can be meaningfully qualified as “liberal”: “Without the adjective, democrats, socialists, nationalists, and all the others can be, and often are, monist, dogmatic, intolerant, and repressive.” The essence of liberalism in this sense is to refine ideology: the adjective “constrains the use of force and makes for pluralism, skepticism, and irony.”

I like those things. But they have limits, a fact which everyone implicitly understands even if some deny it. Walzer doesn’t deny it, to his credit. Liberals, he says, “are not relativists. We recognize moral limits: above all, we oppose every kind of bigotry and cruelty.” So a liberal’s appreciation of “pluralism” doesn’t extend infinitely in all directions. There is a big imaginary black box labeled “bigotry and cruelty,” and inside that box are some things which no liberal, of any variety, can tolerate. What are they?

It seems to me that this question is what’s really at issue in American politics right now. Walzer never spells out an answer. Perhaps, as a member of a generation that enjoyed something approximating cultural consensus, he doesn’t think he has to. Perhaps he thinks we all know bigotry and cruelty when we see them.

In 2023, however, “bigotry and cruelty” can include: building a liquor store in the wrong neighborhood, not building a highway in the right neighborhood, saying the word “picnic,” and, interestingly, writing a sentence like “we are not relativists.” In such a climate, when someone proposes that every commitment should be modified to avoid “intolerance” but also to exclude “bigotry and cruelty,” I would like to know exactly what those words mean.

I don’t think Walzer intends them to include inconsequential microaggressions. In fact, he states outright that some college students, at least, are too easily offended. “Join the argument,” he urges those students; “don’t try to repress it.” I quite agree. But where exactly does “joining the argument” end and “repression” begin? Apparently, it begins precisely at the line marked “bigotry and cruelty.” Where is that line?

To glean an answer, one has to survey The Struggle for a Decent Politics more generally. The book devotes seven chapters to various nouns that Walzer thinks describe him and his friends, each with the all-important adjective “liberal” attached.

Unfortunately, even clubbable socialists can’t bring about peace and social harmony just by being really “open-minded, generous, and tolerant.”

There are liberal democrats, who “defend a state where power is constrained.” Liberal socialists eschew their more radical comrades’ march toward utopia and “the harsh discipline that is required to get there.” Liberal nationalists and internationalists believe in the sovereignty not just of their own nations, but of others as well, and in the possibility of cooperation between them.

And so on: Liberal communitarians make space for private life; liberal feminists tolerate the existence of some patriarchal religious practices; liberal professors allow differing viewpoints in the classroom; and liberal Jews are comfortable with many denominations of Judaism. Liberals acknowledge that it takes all kinds, and so they make plenty of room for those who differ.

But not for bigots. For instance, argues Walzer, the American Civil Liberties Union might have done better not to defend the free speech rights of neo-Nazis in Skokie, Illinois in 1978. By taking up that famous case, the ACLU drew a moral equivalence between Nazis and Civil Rights protestors, both of whom were supposed to deserve protection under the law. But “If they are not morally similar (or even close),” asks Walzer, “do they really have to be treated in the same way?”

It used to be a defining feature of liberalism to insist that yes, all Americans do have the right to speak and demonstrate—morally noxious though their message may be. But of course, self-professed liberals have been hedging on those commitments for some time now. During the Trump years, the ACLU itself circulated an internal memo encouraging staff to consider “the extent to which the speech may assist in advancing the goals of white supremacists” before agreeing to defend it. Walzer, for his part, suggests that “an acknowledgement of possible (not many) exceptions” to “civil liberties absolutism” would “serve the cause of liberal democracy.” I ask again: which exceptions? And another question: who will decide?

In his chapter on “Liberal Feminists,” Walzer enters into dialogue with the work of his former graduate student, the late Susan Okin. Okin once wrote that a truly just society would be structured so that “one’s sex would have no more relevance than one’s eye color or the length of one’s toes.” But as a liberal, Walzer wants to moderate the totalizing demands of extreme feminism to equalize men and women in every way and every context.

Some ethnic and religious communities have patriarchal traditions, and trying to overturn those traditions forcibly by state intervention is likely to backfire: “This is another battle women should fight for themselves,” writes Walzer. In other words, good liberals should bestow an indulgent smile of tolerance upon even regressive cultural practices.

Up to a point, that is. Walzer wants to consider making an exception to discourage the public use of burqas that cover the whole face, since “Human social life is lived face-to-face.” After all, “in a liberal democracy, we would want everyone’s inimitable self freely displayed in public.” This is an odd thing to say, since earlier in the book he stated that emergency COVID measures—which at various times mandated covering the face in all but the most secret recesses of privacy—“seem to me consistent with the commitment of any government, certainly any democratic or socialist government, to public health and safety.”

To recap, then: in Walzer’s liberal world, you must wear a mask if the state thinks it’s good for you, but you shouldn’t wear a mask just because your family says God wants you to. Walzer also thinks “state action was necessary to make gay marriage possible, and it remains necessary to ban discrimination against gays in employment.” But according to both the Supreme Court and the Biden Administration, “discrimination” on the basis of sex and sexuality may now include such things as restricting women’s sports teams to biological females. If you want to run your church or even your basketball league according to the traditional, common-sense meanings of basic words like “man” and “woman,” then the “liberal” state is starting to look very interventionist indeed.

Walzer reports having been instructed by his granddaughter that sex is “not a binary; it’s a continuum.” His consciousness duly raised, Walzer intones: “now that the continuum has been recognized, it is important to make life possible for everyone located anywhere on it.” But one has to wonder what happens when conflict arises between different segments of the “continuum.”

In our present regime, the answer seems to be that women’s rights will take priority—unless they trespass on the sacred ground of transgender rights, in which case TERFs will be bullied and screamed at by men in dresses until they agree to open up their changing rooms. The upshot looks less like an enlightened policy of prudent case-by-case decision making, and more like a hierarchy of favored classes whose interests are pursued with extreme prejudice at the expense of disfavored castes.

What this really means is that liberalism becomes the totalizing ideology par excellence, invisible only because its claims are so far-reaching and so entire.

Exceptions and inconsistencies like this are matters of priority—they depend on what you value and believe. In other words, they depend not on “‘liberal’ as an adjective” but on which noun the adjective modifies. If that noun is “American” (an identity by which Walzer does not set much store), then competing claims on the part of rival factions and individuals should be settled not by some vague reference to what is “liberal,” but by the Constitution and the law. What has become clear in the past 20 years is how many members of our ruling elite feel comfortable running roughshod over the Constitution and selectively applying the law, if their reasons for doing so seem (to themselves) to be sufficiently “liberal.”

This is precisely why words like “liberalism,” “tolerance,” and “pluralism” have lost almost all their former heft and credibility as moral signifiers. It’s not because they encourage “complacency” in the face of screaming injustice which would otherwise demand revolutionary action, as critics to Walzer’s left would argue. It’s just the opposite: “liberal” as an adjective too often underwrites sneering moral certainty and hides the most brazen abuses of justice under cover of concern for the marginalized.

“Liberals like us are best described in moral rather than in political or cultural terms,” writes Walzer: “we are, or we aspire to be, open-minded, generous, and tolerant.” That’s doubtless true, and since Walzer is writing here about “myself and my political friends and comrades,” it’s easy to believe that the people he has in mind really are well-meaning, thoughtful, and great to talk to at cocktail parties. But unfortunately, even clubbable socialists can’t bring about peace and social harmony just by being really “open-minded, generous, and tolerant.” No one can: the wisdom and kindness of even the best men, especially when self-evaluated, are woefully inadequate as metrics of justice.

And a metric is exactly what Walzer wants “liberal” to be: his liberalism is not an ideology, but a measure of how generous and open-minded any given ideology is. Yet what this really means is that liberalism becomes the totalizing ideology par excellence, invisible only because its claims are so far-reaching and so entire. Every creed, every faith, every community must bend to fit its demands, must reform and disavow ancestral traditions that fail to merit description as “liberal.” Those who fall short of this exacting standard—the Trumpists, the fundamentalist Christians, the TERFs—must be consigned to the exterior darkness where there is great bigotry and cruelty.

In truth, though, female athletes like Riley Gaines don’t object to competing against men out of hidebound prejudice: they object on the basis of rational and moral arguments which they believe to be true. Accusing them of discrimination is a way of avoiding engagement with the facial merits of those arguments. As a result, it’s hardly persuasive when Walzer says that “the liberal secular state has been remarkably hospitable to people of every religious and ideological sort.” It seems truer to say that self-professed secular liberals are increasingly comfortable banning any number of communities, practices, and even beliefs, so long as the undesirables can be categorized as intolerant or unkind. Under such conditions, “‘liberal’ as an adjective” is just a new way of making a very old distinction between friends and enemies. Who decides? Us: we’re the good guys. We’re nice. We’re smart. We’re liberal! We keep the bad guys away.

Michael Walzer himself is in fact nice, smart, and liberal. But he’s not in charge anymore. He’s a member of what at this point should be called the “Old New Left,” a vanguard that once set the terms of the movement. Today, this vanguard has been superseded by a far louder, angrier, and more unreflecting group of “radical changemakers” with no doubt in their minds who the good and bad guys are. Based on how placidly he swallowed his granddaughter’s hardline gender criticism, Walzer seems content to let these new Bolsheviks take the helm—and blissfully unconcerned about what it might mean when they do.

It is now possible to find enthusiastic worthies chirping happily about “‘liberal’ eugenics,” which is when the good guys do gene editing and selective abortion (when the bad guys do it, it’s called “‘authoritative’ eugenics”). Since we have already seen what happens when the good guys do bigotry, surveillance, and political persecution, we can look forward with confidence to a bright future of liberalism for all (except, of course, the bad guys). I agree with Michael Walzer that pluralism, tolerance, and kindness are good things. But I also agree with him that they are not sufficient to meet our moment, and I’m not sure he knows what is. The most urgent question of politics in our era is not “what it means to be a liberal,” but “what it is good to be.” For my money, it is good to be an American, which involves believing that human beings are endowed by their creator with certain rights. Since liberty is among those rights, liberalism of a certain sort will characterize any truly American revival. But it will not be enough.