Superpower status brings obligations of leadership. But leadership can be exercised with arrogance or humility and in a spirit of adventure or restraint.

Puritanism as a State of Mind

Recent generations of Americans have become accustomed to hearing their country referred to as a “City on a Hill,” a phrase which usually means that it is, or can be, a moral exemplar. In a 1961 address to the General Court of Massachusetts, President Kennedy introduced contemporary political discourse to the phrase from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:14). Google’s Ngram Viewer demonstrates the proliferation of the phrase after President Reagan famously used it on the eve of his election in 1980 and then closed out his two-term presidency with it in 1989. President Barack Obama deployed the phrase, as have many other politicians in both major parties.

Our recent national self-examination, however, suggests that the top of the hill has become more of an ambition than an accomplishment. Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman’s dynamic “The Hill We Climb,” for example, read at the inauguration of President Biden, articulated America’s moral challenges and returned instead to a more aspirational verse in American political theology: Micah 4:4, the hope that everyone may someday “sit under their own vine and fig tree, and no one shall make them afraid.”

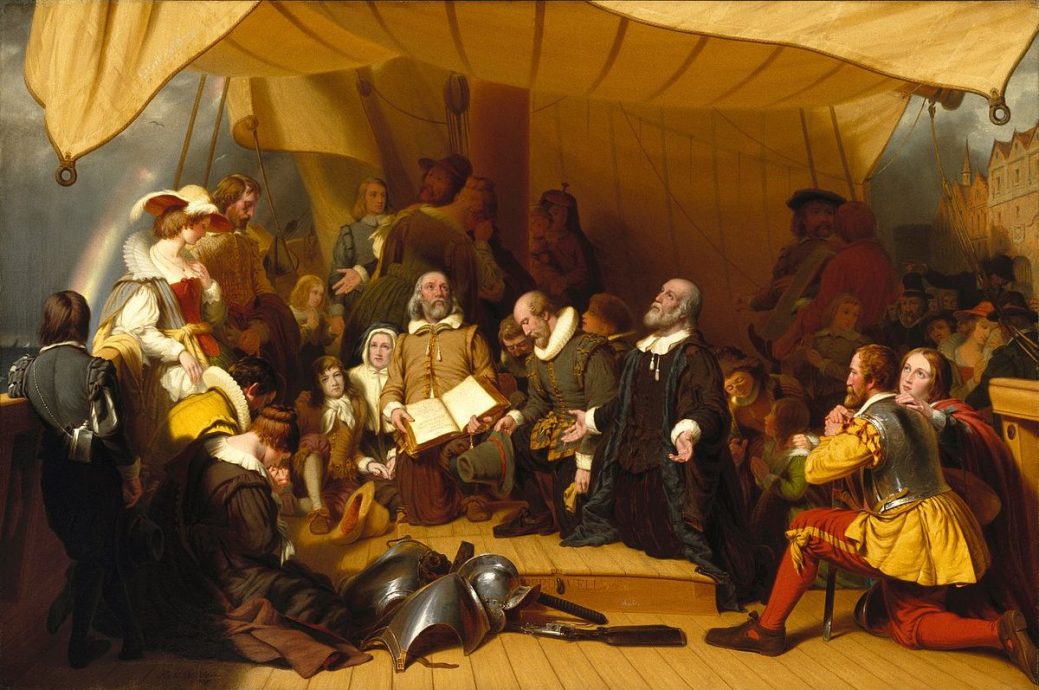

Whatever the “City on a Hill” is, the phrase was not discovered by Kennedy or Reagan, of course. They deployed this scripture not only for its own sake, but to recall its historical use in a sermon by John Winthrop. Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, supposedly delivered the sermon aboard the Arabella just before the Puritan arrival in 1630. The sermon, and its role in American politics, has been the subject of three revisionist studies. In 2012, Hillsdale historian Richard Gamble questioned America’s “redeemer myth” and cautioned against enthusiastic civil religion. In 2018, Princeton historian Daniel Rodgers likewise challenged the invention of “historical myth” and recounted Americans’ wrestling with existential questions of destiny and morality. Winthrop’s sermon, A Model of Christian Charity, gained interest not just because of its historicity, but as an occasion to ask questions about the nation itself.

Much Ado About Winthrop

Why all the fuss about Winthrop’s sermon, especially given the abundance of sermons in Puritan New England? If one were to examine the history or literature curricula in secondary and college education, for example, the answer is obvious: Winthrop’s sermon is often cast as a founding text for America, one of its earliest statements of purpose and identity. It is like the Declaration of Independence, but at the beginning of the nation’s Table of Contents. Some have presupposed a straight line of significance—with Winthrop laying a foundation on which Jefferson, Madison, and subsequent statesmen built.

This is where the historical “Gotcha” starts. The sermon was lost for two centuries after its supposed delivery. It therefore could not have influenced the Founders, or even the early republic. And as the author of City on a Hill, Abram Van Engen, is fond of pointing out, it’s questionable that Winthrop’s Model influenced anyone at all–including the Puritans! Van Engen, like Gamble and Rodgers, demonstrates that the sermon just cannot be found where one would expect to find it in the historical American canon. Even after it was discovered, and eventually published in 1838, no one seemed to care much about it–or at least no more than the rest of the sermons produced in New England over two centuries. Even more surprising, no one cared much about the phrase “City on a Hill” until after World War II. Even Reagan’s use suggested how much Winthrop had become a convenient trope rather than a genuine historical curiosity. Reagan called him a “Pilgrim.” But perhaps Reagan didn’t need to know a Pilgrim from a Puritan since, after all, he was more interested in summoning a powerful national self-understanding of American exceptionalism.

Unlike Gamble or Rodgers, who are more interested in taking exception with that exceptionalism, Van Engen is interested in tracing its lineage. Van Engen begins the substantial part of his argument in the historical archives that enabled Winthrop’s recovery and kept so much early American history from being lost forever. He recounts how archival collections came into existence, often against all odds, thanks to the founders who built and stocked these institutions to enable particular interpretations of American destiny.

Willard’s founding tale of America marginalized everyone but New Englanders.

After establishing themselves in the 1820s, historical societies gathered up the documents now taken for granted by scholars. Protestantism is relevant again here, insofar as these pioneers like Jeremy Belknap or Ebenezer Hazard felt the call of God to their labors. Not only did they think historical scholarship a vocation, the past could be prologue if Americans learned of their ancestors’ love of liberty and deployed the case studies of history for their happiness.

New England as America

Published collections of manuscripts and early printed materials, accompanied by commentaries, struggled at first to pay for themselves but eventually became quite popular. By the 1820s, historical works accounted for more than 85 percent of best sellers. Americans were soon devouring materials about their past. The most important Americans in this story were, of course, New Englanders–a theme that continues today. American Indians, Virginians, Dutch, Spaniards became “problems, not participants” in American history. There were many reasons for focusing on New England, but the most obvious one was that only New England seemed to give America a clear origin point. This meant minimizing, if not erasing, a lot of American history. Tocqueville, for example, took Harvard historian Jared Sparks’s theory of origins, combined it with the Puritan hagiography he found in schools across America for his account of America’s origin. Textbooks authored by Emma Willard launched a revolution in pedagogy and sold over a million copies, each promoting the idea of ‘New England as America.’

Willard’s founding tale of America marginalized everyone but New Englanders. Using a typically fine turn of phrase, Van Engen describes Willard’s work to mean that anyone else “might find America, but they did not found it.” The pious motives of Puritans, and increasingly “Pilgrims, were elevated above the allegedly avaricious motives of other American settlers. Daniel Webster and others solidified the legend of the Pilgrims in the 1820 bicentennial of the Plymouth Rock landing. The striking part about this move to a New England founding of America, still ubiquitous in the thinking of scholars and laymen, was that, as Van Engen describes it, “Before 1820, Pilgrims and Puritans were mostly a regional affair.”

Not everyone joined the New England fan club. Most historians praised their Calvinist forebears, but novelists such as Nathaniel Hawthorne criticized them. Critics such as Methodist minister William Apess urged Americans to break from the past and rebuke it precisely because these first New Englanders were not seeds of liberty, but weeds who choked off freedom. Such criticism was carried forward into academic intellectual history by Vernon Louis Parrington and into more popular journals by H.L. Mencken. James Savage, an antiquarian’s antiquarian, was not just scrupulous in his research of old documents, but scrupulous in his criticisms of Puritans. All, that is, except one: John Winthrop.

While this historiographical war was raging, Winthrop’s Model sermon remained unknown until it was printed in 1838. Its accompanying introduction by Savage leveraged the sermon to encourage courageous American expansion. Community trumped liberty, Savage argued. Greatness of spirit trumped greatness of material acquisition. Still, no one at the time thought of the Model as a founding document, including the New York Historical Society who acquired it from a descendant of Winthrop now living in New York. Even Savage did not reflect on its publication as one of his lifetime achievements. Van Engen writes, “During the first hundred years of the sermon’s life as a printed and public text, A Model of Christian Charity was never linked to the meaning of America and never situated as the origin of the nation.” If scholars and politicians knew it existed, they didn’t care.

The rising star of the first half of the nineteenth century, according to Van Engen, was the Mayflower Compact. It was shorter and more easily placed at one end of a straight line through other constitutional documents and, eventually, to the Constitution itself. If the Model was included in early anthologies, it was edited; those edits revealed more about the editors than about Winthrop. Even Charles Beard’s Progressive historiography could not find something to leverage in Winthrop’s warning against wealth, however much Max Weber’s flawed reading of Calvinism had succeeded in making Puritans the founders of national wealth and power.

Perry Miller’s Puritans

This brings Van Engen to Harvard intellectual historian Perry Miller, the scholar most responsible for sustaining genuine interest in (and admiration for) the Puritans even in the wake of criticisms launched in the nineteenth century. In a series of chapters that make one wish Van Engen would write a biography of Miller, Van Engen writes as much about Miller the man as he does about his responsibility for situating the Puritans in modern American consciousness. Miller lived long enough to hear President Kennedy summon Winthrop, and Kennedy’s assassination three years later probably contributed to Miller’s own untimely death.

Through his influence in literature and history, Miller hoped that Puritanism could become the American state of mind. Miller’s missionary zeal was not what one might suppose; he was not evangelizing for Puritan piety. Miller himself was an atheist, though Reinhold Niebuhr described him as a “believing non-believer.” “Grace” was nothing more than learning mid-twentieth century liberal pieties, and Miller hoped that education could enable a Puritan cast of mind that would rescue American community from American individualism. Puritanism was elevated by Miller above the paltry vision of the Pilgrims or the “incoherent” vision of Virginians, for example.

American Puritanism, according to Miller, should elicit neither idle praise nor idle criticism for its relationship to liberty. He believed that Puritans embodied a paradox that could solve some of America’s moral challenges famously characterized by Life magazine’s Henry Luce (one of many influential children of missionaries) on the eve of World War II. And though Miller eschewed imbuing the Puritans with national moral significance before his service in the war, he changed his mind thereafter. Miller soon shared the concern of influential Americans such as Billy Graham that the nation lacked a sense of purpose. That sense of purpose would only come, Miller believed, through the kind of self-criticism at which Puritans excelled.

Van Engen’s study of Miller is full of anecdotes from Miller’s students to make his point. Here I will add yet another from a fellow scholar of Puritanism, church historian John Gerstner. Gerstner and Miller were both admirers of Jonathan Edwards, and Gerstner would tell the story of attending a lecture with Miller. Afterwards, Gerstner commented that the speaker did not emphasize enough how redemption came only after great trial and searching. Miller slammed his drink on the table and exclaimed, “That’s right, Gerstner, that’s right.” Miller, thinking in moral or rational terms, believed that only when Americans gave up their cheap grace or easy-believing (i.e., their complacency) would they find their national calling. Winthrop’s Model, for Miller, could become a founding document for this search.

Winthrop’s Model Today

This idea of the jeremiad not so much as a means of redemption, but a tool of rhetoric, was advanced later by Sacvan Bercovitch, another legendary scholar of American Puritanism. Van Engen’s study of Bercovitch brings the book back around to the question of the Model and why it became so significant. So far as Van Engen is concerned, Bercovitch leveraged it through questionable scholarship to advance not so much a normative vision of America, but a study of its political tropes. Van Engen concludes with engaging commentary on contemporary politics, including the repeated use of “City on a Hill” to claim the moral high ground against Donald Trump.

Van Engen, a professor of literature, has written a remarkable work of historical scholarship. He is rightly curious about things like which Bible Winthrop used for his text, or the provenance of Winthrop’s sermon, for example. He doesn’t get bogged down in theological concepts like the covenant or typology, but he does pertinently and prudently deploy theological background where appropriate. He tersely makes the point that Winthrop had much better scripture for triumphalism. In short, it is hard to read Winthrop to mean what twentieth-century Americans read him to mean. Furthermore, differences between Catholics and Protestants had stark differences about what “City on a Hill” meant for the identity of the church, with Catholics claiming a more triumphant role for the church and Protestants casting the church more as a “little flock.” (Roman Catholic JFK used the latter interpretation.) Though Van Engen does not say so, this debate about whether the church is a ruler or a remnant is arguably the most significant contemporary debate in contemporary American Protestantism.

And though Van Engen’s book is often about historiography and the purpose of history, subjects that threaten to become quite dry, he avoids the deep weeds and tedious minutiae. Concerning the more obvious controversies of the woke variety, Van Engen acknowledges budding theories of supremacy in eighteenth century historiography, but he resists becoming a boring scold of dead people. He has something interesting, even new, to say not just about one familiar thing, but about many. His prose is engaging and filled with many fine turns of phrase. His argumentation is seamless, never forced, and the story he tells is fascinating. City on a Hill should encourage us to reconsider what we think we know about both history and historians.