Talk Radio, Take One

For decades, historians of the American conservative movement (sympathetic to conservatism or not) have emphasized the extraordinary importance of writers, especially the conservative intellectuals and journalists associated with National Review. This has been the case at least since George Nash published his indispensable history of post-war American conservatism in 1976. For researchers, this is convenient. If such an approach tells us most of what we need to know about the American Right, understanding conservatism’s history largely entails reading back issues of a handful of well-known magazines. I should admit that, in my own work on 20th-century right-wing thought, I also focused on the written word.

To hear some conservatives describe their own history, a dozen or so writers at a single journal of opinion turned the tide of history: William F. Buckley and National Review were responsible for Barry Goldwater’s rise, which paved the way for Ronald Reagan, who then personally won the Cold War and rolled back American liberalism. However, as Paul Matzko notes in his excellent new book, The Radio Right, the “Buckley-centric narrative” of conservatism’s history leads to “historiographical oversight.”

When we think about conservatism’s rise, we must of course recognize the role played by intellectuals and journalists associated with highbrow publications, but they were not the only purveyors of conservatism in post-war America. To take one example, most of us are familiar with the John Birch Society. The fact that Buckley’s successful war on Robert Welch and his organization is treated as a critical moment in conservatism’s history is one reason for that familiarity.

In the 1960s, however, there were conservative figures with a larger reach, at least in terms of sheer audience, than either Welch or Buckley. At a pivotal period in U.S. political history, long before Rush Limbaugh sat in front of his golden EIB microphone, right-wing broadcasters were entering millions of homes via the AM radio. On hundreds of stations, a new breed of radio broadcaster was sending out populist, anti-communist, evangelical, and often pro-segregation messages.

Radio, Segregation, and the Rise of a Movement

Matzko suggests that right-wing radio broadcasters were a crucial, but now mostly forgotten, element of the Republican Party’s rise in the South. This was largely because conservatives on the radio offered full-throated defenses of racial segregation. They were not unique in this, of course. Buckley and National Review, for the most part, took the segregationists’ side during the civil rights era. However, with a few exceptions, they preferred not to defend segregation and white supremacy as such, instead making arguments about the limits of federal authority or Burkean claims about the superiority of incremental change over radicalism. The conservative radio personalities, who reached audiences that had never heard of William F. Buckley, did not bother dissembling, and offered a less diluted form of right-wing populism.

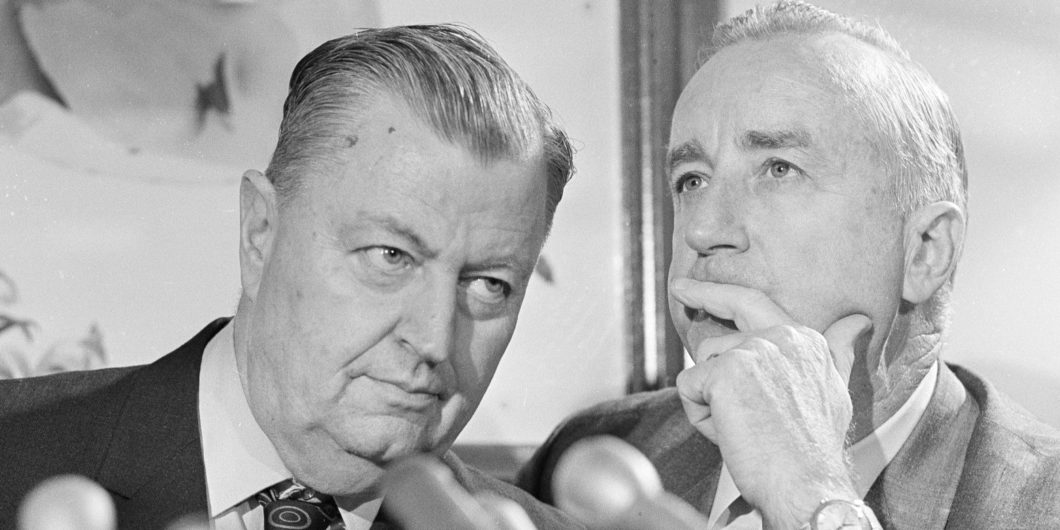

It is especially important that the most influential of these radio programs were not hosted by traditional Southern Democratic segregationists. Many were Northern Republicans. The evangelical broadcaster Carl McIntire, for example, was a Republican from New Jersey. His evangelical Christian program, Twentieth Century Reformation Hour, which included copious political content, aired on hundreds of radio stations in the South. Programs like McIntire’s promoted a traditional conservative message, but also offered a full-throated defense of Southern mores when it came to race.

Although one should be cautious about inferring cynical motivations to explain why media figures take particular positions without solid evidence, there may have been a practical reason for McIntire to take such a stand: it resulted in a massive audience for his show. The fact that McIntire had shown relatively little interest in racial questions in the early years of his career suggests this was a calculated move. The Northern roots of these broadcasters also benefited the Southern segregationists, who could point to support outside their region. As Matzko put it: “Thumping the pulpit for segregation meant more listeners, more radio stations, and more donations for McIntire. For massive resistors, support from nonsouthern broadcasters was used in the (failed) effort to deflect accusations of racist intent.”

According to Matzko, these radio hosts played an indispensable role in breaking down the partisan identities of white Southern Democrats, clearing the way for their embrace of the GOP: “[B]roadcasters served a vital function in the partisan transformation of the Deep South. They made it possible for white southern segregationists to imagine that the Republican Party, which many had hated their entire lives, could really be relied upon to be the new home for massive resistance to desegregation.”

Although the Fairness Doctrine was intended to ensure a balanced discussion on the public airwaves, in practice it was used to silence voices that opposed the Democrats in the White House.

As the battle over civil rights continued, conservative broadcasters such as McIntire and Billy James Hargis, host of the radio program, The Christian Crusade, proudly promoted segregationist politicians. McIntire gave his enthusiastic support to George Wallace and Strom Thurmond, which was rewarded with high praise from both men. Hargis invited Wallace to address one of his gatherings of evangelical Christians.

When we think about the rise of conservative talk radio today, we understandably first think of Limbaugh and others who became so dominant on the AM dial in the 1980s and 1990s. The question is, why the gap? Why did these explicitly partisan, populist radio voices suddenly grow, seemingly from scratch, starting in the 1980s, given this earlier precedent? The reason is that, starting in the 1960s and continuing for over a decade, the federal government used every tool at its disposal to shut down conservative radio, to the point of making it effectively illegal.

An Unfair Doctrine

Matzko is not the only scholar to examine the first generation of conservative broadcasters. Historian Nicole Hemmer also described this subject in her useful book, Messengers on the Right, for example. Matzko’s explanation of the extraordinary steps Presidents Johnson and Kennedy took to shut down conservative radio, however, is his book’s most unique contribution.

President Donald Trump is consistently decried as an authoritarian for his attacks on his critics in the press. In truth, Trump’s attacks have consisted of little more than angry tweets. As has been the case with so much else in his presidency, these rhetorical assaults have amounted to a lot of bluster followed up with nothing. Modern American journalism has a lot of problems, but President Trump is not their source.

In contrast, Kennedy and Johnson had the full weight of the American bureaucracy behind them, as well as powerful allies outside government. They used every tactic available to them in their successful war on conservative radio. The Reuther Memorandum of 1961, written by the Reuther brothers (important labor leaders) and distributed throughout the Kennedy Administration, outlined a strategy for taking down the “far right”—a category that included, I should note, Barry Goldwater and his supporters. This memo suggested, for example, that the IRS should target and harass non-profit groups that promote right-wing messages, denying them tax-exempt status.

Matzko takes a remarkable dive into various archives, detailing the ways Kennedy and later Johnson went after right-wing radio. Their primary weapon was the “Fairness Doctrine,” which called on broadcasters using the public airwaves to provide a balanced perspective on current events. An especially important element to this doctrine was that, if a radio program attacked a particular group or individual, the target of the attack had to be given an opportunity to respond—typically free of charge. It would furthermore be the individual station owner’s responsibility for covering this cost. Small radio stations working with shoestring budgets had previously been delighted to host conservative programs. Whatever their ideological preferences, these programs generated revenue. However, if after every program they had to offer free airtime to anyone Hargis or McIntire had attacked that day, it would be better to air no political programs at all. Many stations chose this route, and conservative political views began disappearing from the airwaves.

As Matzko shows, the FCC was deliberate and relentless in its efforts to take down right-wing radio. It furthermore had plenty of allies outside of government to assist them—helping the White House keep its hands clean. The liberal National Council of Churches was especially important in this regard. The largest mainline Protestant organization in the country was a regular target for fiery right-wing evangelicals, and thus the NCC was more than happy to help the FCC drive these voices from the air.

One might expect the pressure on conservative radio to have eased up a bit after Nixon’s victory in 1968. But Nixon had no personal love for the mainstream conservative movement, let alone right-wing radio firebrands. These figures had always viewed him with suspicion, and letting them off their leash was not in his political interests. Perhaps more importantly, Nixon appreciated the precedent set by his predecessors, and was eager to use the federal bureaucracy against his own political enemies.

Perhaps ironically, President Carter’s decision not to use the FCC for personal political aims may have contributed to his loss in 1980. In the years leading up to his presidential run, Ronald Reagan reached perhaps 20 million Americans a day with his radio program, Viewpoint, further building his national audience. A president more like Kennedy, Johnson, or Nixon would have probably used the Fairness Doctrine to shut down that nascent threat.

Matzko’s story presents few sympathetic characters. He does not defend the message of segregationist radio broadcasters, but he suggests we should worry about the ease with which their constitutional rights were trampled for transparently partisan purposes. Although the Fairness Doctrine was intended to ensure a balanced discussion on the public airwaves, in practice it was used to silence voices that opposed the Democrats in the White House. People who admire Kennedy and Johnson, and say their actions were justified, should perhaps remember that, if policies such as the Fairness Doctrine were in place, Donald Trump may not have been such a toothless president.

Although the Fairness Doctrine and its selective application effectively killed the first major wave of conservative talk radio, Matzko relayed an anecdote suggesting McIntire, Hargis, and the others pushed mostly out of business had, in the long run, a revenge of sorts. In the late 1970s, a fateful meeting occurred at an anti-Fairness Doctrine rally. It was in this context that an evangelical preacher named Jerry Falwell met an insider political activist named Paul Weyrich. In their subsequent conversations, they laid out a plan for an organization that would later be named the Moral Majority, setting the stage for the new Christian Right of the late 20th century.

Working through the massive amount of material needed to tell this story was unquestionably a tedious task for the author. It is thus especially remarkable that Matzko wrote such a lively, engaging book. For a more complete understanding of the conservative movement’s rise, including its more unsavory aspects, as well as the equally disturbing efforts to smother it in its infancy, I strongly recommend The Radio Right.