David Forte explains how the Constitution provides the criteria for evaluating America's best presidents.

The Enduring Strength of the American Presidency

By the time the Constitutional Convention met in 1787, the Convention’s delegates had experienced a decade of experimentation on how best to organize a republican government. One striking lesson was the difference in effectiveness of the executive in two neighboring states, Pennsylvania and New York. Although the executive in each shared virtually the same list of authorities, Pennsylvania’s executive was thought to be the weakest politically while New York was perceived to be the strongest. The key differences were the institutional makeup of each and the fact that New York governor held a qualified veto, which provided him a tool to help shape legislation as well as prevent the legislative branch from simply running roughshod over the governor’s own authorities.

The Convention delegates understood that, in terms of crafting an executive office, they needed to pay as much attention to the office’s institutional features as to its actual powers. They thought that only after the office had been properly set up (a single executive with a four-year term, no restrictions on re-eligibility, a fixed salary, and a qualified veto) could a full complement of authorities responsibly rest with the nation’s chief executive. They had, in short, a fulsome understanding of the presidency, seeing it as a complex combination of authorities, duties, and institutional features—all resting under the aegis of the Constitution and designed to remain effective over time, in divergent circumstances, and with future occupants who were unlikely to have George Washington’s stature.

Testing this more fulsome understanding is the central feature of Jordan T. Cash’s The Isolated Presidency. While not dismissing out of hand the various historical and political science approaches to understanding the American presidency and presidential behavior, Cash argues “that the Constitution creates an empowering logic in the presidency through the office’s structure, duties, and powers,” and “that much of the scholarship on the presidency underestimates how the Constitution forms the fundamental backdrop of presidential activity.” Cash tests this thesis by examining three presidents—John Tyler, Andrew Johnson, and Gerald Ford—who “were isolated from other branches of government, their own political parties, and the people.” Weak by virtually every measure of “externality,” left with only their constitutional authorities and institutional qualities to rely on, these three occupants of the White House provide “the clearest view of the presidency’s constitutional logic and the strength that results from it.” Stripped bare, these “isolated” presidents provide a base case for just how powerful the underlying capacity of the presidency can be.

First is John Tyler (1841–45). Tyler succeeded William Henry Harrison, who died one month after being sworn in as president. Tyler was the first to ascend to the office while serving as vice president, leading some to argue that he was not in fact “president” but only an “acting” chief executive. And while Tyler ran on a Whig ticket and had, prior to becoming president, adhered to Whig views about Congress’s supremacy in the constitutional order, once in office, he took a more assertive view of the presidency’s place in that order—indeed, so much so that the Whigs eventually expelled him from the party. In short, Tyler could claim neither an electoral base of support nor the support of a party.

Whig control of both houses of Congress largely stymied Tyler’s domestic policy agenda. Nevertheless, with what was then an unprecedented use of the veto power, Tyler blocked major Whig agenda items, such as re-establishment of the National Bank. He also fought off Whig views on administration: he reasserted presidential control over the cabinet and subordinate officials through his use of removal and appointment powers, along with his authority to make recess appointments.

On the national security front, Tyler made use of the presidency’s multiple advantages over the flow of information from abroad—including the ability to act secretly and decisively—to expand on his own the US’s reach in the Asia-Pacific region. He opened ties with China; recognized Hawaii diplomatically; and extended the Monroe Doctrine to cover the island state. When frustrated by the super-majority requirement in the Senate to approve the treaty annexing Texas, Tyler exploited divisions within the Whig Party, in combination with Democrat support for the measure, to have the annexation completed by the novel use of an executive agreement sanctioned by simple majorities in the House and the Senate.

Second is Andrew Johnson (1865–69). Johnson, a Southern Democrat from Tennessee, was chosen by Abraham Lincoln as his running mate as part of a national unity ticket. Lincoln’s assassination left Johnson with a Cabinet, administration, and Congress dominated by Republicans. Like Tyler, Johnson could claim no broad electoral support. Moreover, with the vast majority of Democrats residing in states still under martial law, he could not look for allies in that direction. To make life even more complicated for Johnson, Republicans—animated by the party’s extant views about congressional supremacy—were determined to rein the presidency back in after the exigencies of the Civil War had passed.

Like Tyler, Johnson’s clearest successes were tied to foreign policy, with the most notable being the purchase of Alaska from Russia. While the Russians initiated the discussions, Johnson was able to use the president’s ability to negotiate the terms of the sale in secret and then to call the Senate into a special session to consider its ratification. By exercising that prerogative, Johnson forced the Senate to take up the treaty—which was popularly supported—and not bury it in the Foreign Relations Committee, as the Senate initially had appeared ready to do. Johnson also succeeded in setting the conditions that led to the toppling of the French-installed monarchy of Maximilian I in Mexico. Johnson declined to formally recognize the new government, refused to abide by that government’s blockade of key Mexican ports, ordered thousands of troops to the south of Texas, and pressured Napoleon III to pull his troops out of Mexico to preserve peace between the United States and France—all done through the unilateral exercise of key presidential authorities.

Through these three case studies, Cash makes a detailed and persuasive case for the enduring institutional and constitutional strengths of the presidency.

Johnson enjoyed considerably less success on the domestic front, but what he did achieve was still significant—and problematic. His initial effort to establish a relatively lenient reconstruction policy toward the Confederate states was overturned when Republicans in Congress passed more restrictive statutes and overrode Johnson’s efforts to block those measures with vetoes. Nonetheless, Cash notes that Johnson, using his appointment and pardon powers, was able to implement “a major component of his restoration policy.” As such, Johnson “preempted Congress and the courts” from “weigh[ing] in on determining the status of the treasonous Southerners.” Although unable to prevent the passage of civil rights measures—including the Fourteenth Amendment—that were intended to integrate former slaves into the American political order, Johnson’s unilateral use of these authorities made it possible for white supremacists to begin to regain their footing in the South.

Johnson’s final “victory,” was his escape from an impeachment conviction by a single Senator’s vote. At issue was Johnson’s unilateral decision to fire Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, ignoring the Tenure of Office Act that required Senate concurrence to remove cabinet officials. Johnson argued that his constitutional duty to see that the laws were faithfully executed meant that he must have the power to remove officials. His relationship with cabinet officials was, he asserted, “analogous to that of principal and agent.” By the skin of his teeth, and against considerable odds, Johnson was able to reassert executive unity and, Cash concludes, “the importance of structural responsibility in the administration.”

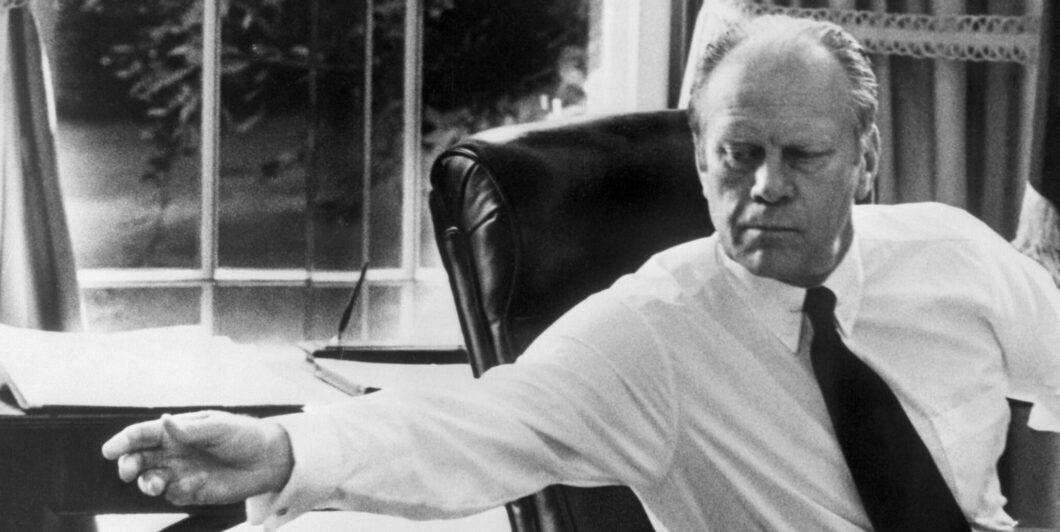

Last is Gerald Ford (1974–77). Compared to Tyler and Johnson, Ford was the most isolated of the “isolated presidents.” Approved by Congress to fill the vacancy created by Vice President Spiro Agnew’s resignation in the fall of 1973, he then stepped into the president’s shoes when Richard Nixon resigned less than a year later to avoid impeachment. Unlike Tyler and Johnson, Ford could not even claim to have been on a winning national ticket. While Ford entered the Oval Office with a favorable approval rating, that number sharply declined following his controversial decision to pardon Nixon in early September 1974. Hemming Ford in further, Democrats swept to super-majorities in both the House and Senate in that November’s elections.

Ford’s presidency, coming in the wake of Vietnam, Watergate, and headline-grabbing revelations about FBI and CIA operations at home and abroad, was never going to be easy. Congressional Democrats were determined to curtail the so-called “imperial presidency” of the post-World War II era. As a result, Ford’s domestic agenda was largely one of playing defense, using his veto power to try to curtail federal spending and to stave off statutes that the White House believed encroached on the president’s core authorities. Given the political environment he found himself in, Ford was moderately successful. This was similarly the case concerning foreign affairs. Democrats were generally opposed to any use by the president of the military, and Republicans were increasingly divided over the Henry Kissinger-led policy of détente. Yet Ford, using his institutional capacity to act first and decisively so, was able to employ the military to evacuate thousands of Vietnamese and Cambodian allies as the war in Indo-China was coming to a disastrous end. He also completed the negotiations and the signing of the Helsinki Accords—a declaration that was intended to re-affirm détente—and began talks that eventually led to a treaty giving Panama control of the Panama Canal.

The Isolated Presidency provides a wealth of worthwhile insights. First, one that doesn’t make it into the author’s conclusion, but is nevertheless obvious from the case studies, is just how important the choice of a vice president can be. Given the age of the likely presidential contenders this November, it’s a point worth highlighting. Second, as Cash correctly reminds us with respect to the Johnson presidency, the level of discretion constitutionally wielded by a chief executive is no guarantee that it will be used to the benefit of the nation. Similarly, even a weak president, like Ford, can arguably make a statesman-like decision that has no popular support. Character remains a critical element in assessing who should and who should not be president.

Third, as Cash’s history of the three presidents brings to the fore, there is no getting around the fact that as a global power, with global interests and alliances in every key region of the world, America inevitably will have a presidency that can look “imperial.” As Tocqueville remarked in Democracy in America, the presidency of that time was “less strong” in comparison to the monarchs of Europe. But, he observes further, “one must attribute the cause of it perhaps more to circumstances than laws.” It is “principally in relations with foreigners that the executive power of a nation finds occasion to deploy its skill and force.” Potentially, a president “possesses almost royal prerogatives” in the right “circumstances.”

In fine, through these three case studies, Cash makes a detailed and persuasive case for the enduring institutional and constitutional strengths of the presidency. Indeed, as he notes in the book’s conclusion: “That the three isolated presidents independently came to embrace a Federalist view of the presidency is all the more remarkable given they came from different personal and political backgrounds, had distinct policy goals, and operated in diverse historical contexts.” When it comes to the presidency, the Constitution really is a “living” document in its ability both to ground presidential behavior and to secure its place in the political order, through the thick and thin of partisan divides and the ever-evolving circumstances a nation faces. It’s an office, as the Founders intended, with more than powers; it’s an office with institutional qualities and perspective and, lest we forget, explicit duties to faithfully execute the laws; and it’s an office to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution.