The Philosophy of Pride

Bernard Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees (1714) was one of the most scandalous books of the Enlightenment. As its most memorable argument is that private vices produce public benefits, it is not difficult to see why. This message, announced already in the subtitle of the book so that it could not be missed, was clearly disturbing to a culture steeped in Christianity as well as the ideals of ancient virtue. Mandeville tried to defend himself against criticism by claiming that he wrote satire. Yet Robin Douglass argues in his new book, Mandeville’s Fable: Pride, Hypocrisy, and Sociability, that we should take the Anglo-Dutch man of letters (and daytime physician) seriously as a philosopher.

Douglass is in good company: the Scottish Enlightenment’s David Hume placed Mandeville alongside John Locke as one of “the late philosophers in England, who have begun to put the science of man on a new footing.” Hume’s remark is suggestive, but he never explained exactly what he took Mandeville’s precise contribution to the “science of man” to have been. By contrast, Douglass’s book painstakingly explicates Mandeville’s precise philosophical significance. The result is impressive, unexpected, and unsettling in equal measures.

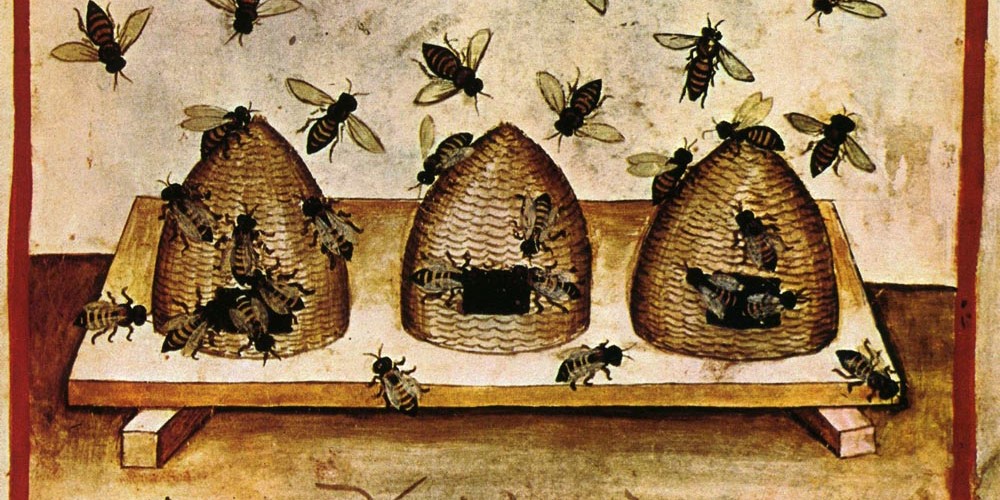

We are sometimes told that if modern readers are searching for the origins of Gordon Gekko’s motto “Greed is good,” we ought to look to Mandeville rather than to Adam Smith, who did not think highly of merchants. In the 1705 The Grumbling Hive, Mandeville used a prosperous beehive as a metaphor for contemporary England, a growing commercial nation, to which he had emigrated from the Dutch Republic a decade earlier. In this verse he wrote in his non-native language, of which he had become a master:

Thus every Part was full of Vice,

Yet the Whole Mass a Paradise;

Flatter’d in Peace, and fear’d in Wars

They were th’Esteem of Foreigners,

And lavish of their Wealth and Lives,

The Balance of all other Hives.

Such were the Blessings of that State;

Their Crimes conspir’d to make them Great:

And Virtue, who from Politics

Had learn’d a Thousand Cunning Tricks,

Was, by their happy Influence,

Made Friends with Vice: And ever since,

The worst of all the Multitude

Did Something for the Common Good.

When remembered today, Mandeville is often considered in the context of economic thought. But one of Douglass’s key moves is to decenter the focus from private vices and public benefits, and the common caricature of Mandeville as philosophy’s Gordon Gekko. This makes sense. If Mandeville had not offered anything more than a notorious defense of aggressive capitalism, the high praise from a philosophical genius like Hume would have been hard to understand. Instead, Douglass provides a sympathetic account and a qualified defense of Mandeville’s pride-centered and historical theory of human sociability.

Pride and Sociability

Theories of sociability—that is, explanations for why human beings associate with one another, form societies and states, and follow social norms—were central to early-modern philosophy. A starting point was Hobbes’s repudiation of Aristotle’s claim that man was born fit for society, as a zoon politikon. For Hobbes, it is our quest for glory and power that makes us need our fellow men, and communal ties need to be fostered and enforced by the state, created through a social contract.

Early-modern philosophers grappled with Hobbes’s sometimes disconcerting conclusions, and some even appeared to rehabilitate aspects of ancient philosophy in the process. Notably, the Third Earl of Shaftesbury, Locke’s renegade pupil, argued in the early eighteenth century that sociability is natural to humans, and he went as far as saying that our generous affections can lead us to promote collective welfare. Later in the century, Immanuel Kant developed a theory of “unsocial sociability” that held that humans are equally likely to enter society as they are to isolate themselves, and are in a way both collectivist and selfish. But no theory was more shocking than Mandeville’s.

For Mandeville, it is pride—the passion that makes us care, and indeed obsess, about how other people think of us, and our tendency to overvalue our worth—that is the predominant quality explaining human sociability. While pride is an innate principle of human nature, the precise form it takes is socially determined and varies according to the customs and habits of particular people and cultures at different times. But Mandeville’s key point is that it is our pride that drives our need for other people, as we seek society in pursuit of social esteem.

Our self-centrism means that we are not born sociable but are shaped for society through a process of education. For example, as young children are less ashamed to display their egotism, they need to be educated to show sufficient self-restraint to be bearable company to people other than their parents, whose natural affection for their offspring tends to make them more forgiving than others. In short, we are taught to be hypocrites in order to be sociable creatures.

Although hypocrisy has this useful function, Mandeville recognizes that there are malicious hypocrites, particularly intolerant people who, in Douglass’s words, “like to portray themselves as exemplars of virtue with the authority to castigate the shortcomings of others and demand a moral reformation.” It is not difficult to think of present-day examples in our age of cancel culture.

That pride is the animating and motivating passion behind a great deal of human behavior is a fact often hidden from us, as we have internalized its authority. But we can frequently recognize its force. Most of us are worried that we do indeed overvalue ourselves, and we therefore seek the approval of others to “ease our anxiety and confirm our estimation of our own worth.” And we sometimes feel even prouder when we manage to refrain from outwardly displaying our pride. For many readers, grappling with Douglass’s deft treatment of Mandeville will inevitably lead to an unsettling self-examination. This is part of the book’s intention. As Douglass writes in the preface:

[Mandeville] leaves you questioning yourself in a way that is true of much of the psychologically richest philosophy and literature. You can go away and read Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments and feel a bit better about yourself, but when you come back to Mandeville the doubts soon return.

A Historical Turn

Mandeville’s theory is not quite as unique as it sounds. Other thinkers who either predated or followed Mandeville used terms such as esteem and recognition to explain human sociability. Perhaps most famously, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who had read Mandeville, immortalized the concept amour propre (a more complex and comparative form of self-love, distinguishable from self-preservation). The difference between these concepts and pride, Douglass explains, is that pride has a negative connotation, being associated with original sin in the Christian tradition. We can understand how controversial Mandeville was in his own time (and in many ways still today) by recognizing that he used a term strongly related to vice—and, Douglass shows, we have reasons to believe Mandeville actually thought of pride as essentially vicious—to explain the foundation of the entire social fabric.

In contrast with Hobbes and Locke, Mandeville did not rely on social contract theory to explain the foundation of politics. Douglass argues that what made Mandeville’s theory of sociability innovative was its historical dimension, as he sought to chart human development from rudimentary, “savage” beginnings to civilization. History in this context is what Scot Dugald Stewart would term conjectural history—a philosophical investigation that uses conjectures based on human nature to explain how social institutions are likely to have arisen and evolved at earlier epochs for which there is no surviving evidence. Accordingly, Mandeville can be said to have paved the way for Rousseau as well as the great thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment such as Hume and Smith (though Paul Sagar has recently questioned Stewart’s categorization of Smith as a conjectural historian).

Mandeville placed the desire for superiority and dominion at the heart of his conjectural history of the beginning of society, which needed leaders to emerge among “savage families.” But since our pride makes us want other people’s affirmation of our opinion of our superior worth, it must have been difficult for leaders to arise, which meant that bands of savage families for a long time would have needed a common enemy to stay united. Eventually warlords must have invented politics and laws to curb the pride of their inferiors, who became the governed. For Mandeville, the workings of leadership and obedience were thus learned through a long and arduous process of socialization.

This book is not only for those who are sympathetic to Mandeville’s philosophy. Though closely focused on its protagonist, it is contextually rich, and tells us much about the wider philosophical landscape in his day. The fact that this wider literature is examined intentionally and transparently through a Mandevillean lens is not overly troubling, but rather gives fresh perspectives on familiar thinkers. Among other things, we learn about the French “neo-Augustinians” such as François La Rochefoucauld who put pride at the heart of their enquiries in the seventeenth century.

Unquestionably, Douglass has done enough to show why Mandeville was such an influential figure in the eighteenth century and why we should pay more attention to him today, not by telling a reception history but rather by giving us the most comprehensive and convincing interpretation we have of Mandeville’s philosophy to date.

Douglass notes in several places that Mandeville’s relationship to Christianity is a contested topic among scholars, and that the available evidence does not tell us much for certain about his personal beliefs. For many of his contemporary readers, the “private vices, public benefits” paradox was clearly tantamount to atheism. But in a significant dialogue in Part II of The Fable of the Bees, the character usually taken to be representing Mandeville emerges as a faithful Christian, and his opposite and the detractor of The Fable is a skeptical Deist. While some readers have regarded this as an ironical pose, Douglass contends that the more plausible interpretation is that Mandeville—whatever his own religious beliefs (or lack thereof) may have been—was eager to show that his arguments were consistent with Christianity. Crucially, in revealing the corruption of human nature and the limitations of human reason and pagan virtue, Mandeville argued that he had strengthened the case for Christianity and revelation. By contrast, the likes of the Third Earl of Shaftesbury “endeavor’d to sap the Foundation of all reveal’d Religion, with Design of establishing Heathen Virtue on the Ruins of Christianity.”

One of the book’s many strengths is the emphasis it places on objections to Mandeville’s system from his contemporaries. Francis Hutcheson, sometimes known as the Father of the Scottish Enlightenment, and the Anglican theologian Joseph Butler emerge as sharp critics of Mandeville’s “selfish” system in the 1720s. Hutcheson and Butler both impacted Hume and Smith, who continued to criticize Mandeville later in the eighteenth century. As Hume wrote: “I feel pleasure in doing good to my friend, because I love him; but do not love him for the sake of that pleasure.” Smith conceded that human beings want to be praised, but he believed that Mandeville had failed to see that what we really desire is to be worthy of praise. In other words, both Hume and Smith can be viewed as seeking to reclaim a space for moral virtue. This leads to the obvious question, addressed by Douglass in the conclusion: Was Mandeville right?

Was Mandeville Right?

Douglass closes the book by arguing that Mandeville was right about certain aspects of human sociability and wrong about others. In various places in the book, he draws attention to where modern scholars working in different fields have corroborated Mandeville’s theses. Modern studies in social psychology, for instance, have confirmed the prevalence of self-serving biases, post-hoc rationalization of our conduct, and moral hypocrisy. Anthropological and ethnological research has demonstrated that the desire for dominion might be a universal human trait. Though these studies have not been unopposed, Douglass believes that they illustrate that we have not gone beyond the paradigm developed by Mandeville. Perhaps most importantly, Mandeville’s approach underlines the value of historical and sociological ways of studying politics.

Unlike the many thinkers he provoked and inspired in the Age of Enlightenment, Mandeville is not a household name today. The only thing missing from the book is perhaps a suggestion as to why such a powerful thinker and writer has been comparatively neglected. Since Mandeville’s Fable is not primarily a historical book this is not Douglass’s question, but it is one which his rich material allows us to ask. It would be tempting to think that one reason may simply be his notoriety, but that would be difficult to square with the canonicity and general popularity of the likes of Machiavelli and Nietzsche.

Another possible reason is that his most important work, The Fable of the Bees, is a complicated text with an even more complex publication history. The first part of it appeared in verse as The Grumbling Hive in 1705, which later formed part of the first edition of the Fable, along with a sequence of “Remarks” on the verse and an essay entitled “An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue.” In 1723, an expanded work of The Fable was published with yet more essays, and in 1728 a “Part II” with a series of dialogues defending the text. The Fable then had a self-described sequel in the 1732 Enquiry into the Origin of Honor, and the Usefulness of Christianity in War. But such an intricate publication history was not too unusual in the eighteenth century, and is comparable to Hume’s oeuvre. And, as Douglass remarks, Hobbes’s political philosophy was formulated across several works, written in both Latin and English over several decades.

Neither the form nor the genre and publication history of The Fable can therefore satisfactorily explain Mandeville’s relative eclipse. The most plausible reason may be that he was overshadowed and to an extent supplanted by the thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment, who used his method and partially accepted and built on some of his conclusions (though of course they rejected others). Hume is often said to have offered a theory of “commercial sociability,” but his story of the origin of government and justice in the third book of A Treatise of Human Nature, as well as in his posthumous essay “Of the Origin of Government,” tells a comparable story to Mandeville’s about how tribal warlords turned into political leaders. The latter essay contends that the “Love of dominion is so strong in the breast of man.” Moreover, what Mandeville had to say about commerce was superseded by Hume’s advances and even more emphatically by Smith’s. As Douglass observes, reading Hume and Smith, despite all their skepticism, is certainly more flattering to the human character than reading Mandeville. Mandevillean reasons can thus help us understand why they have remained more popular than him.

The Moral of the Story

Unquestionably, Douglass has done enough to show why Mandeville was such an influential figure in the eighteenth century and why we should pay more attention to him today, not by telling a reception history but rather by giving us the most comprehensive and convincing interpretation we have of Mandeville’s philosophy to date. His scholarship is impeccable and a model to be emulated; indeed, the book’s footnotes provide a guide to further reading for anyone interested in not only Mandeville but also his better-known interlocutors and critics (friendly or otherwise), and in early-modern philosophy more broadly.

While specialist scholars have by no means ignored Mandeville, there are only a handful of monographs dedicated to his thought. For this reason alone, this book is essential reading for anyone interested in the political philosophy of the Enlightenment period, which did so much in laying the foundation of modern politics. But for the most compelling reason why studying Mandeville is worthwhile, we must return to the book’s preface, in which Douglass writes:

One of the consequences of spending a lot of time with Mandeville is that it helps you to recognize some of the pathologies of taking yourself and what you do too seriously. He was particularly scathing of the “great Opinion Scholars have of themselves,” especially those who regard their vocation as more noble or valuable than most other professions … I suspect that working in academia has heightened my sense that Mandeville still speaks to us now.

In other words, don’t take yourself too seriously: you are only a flawed human. Pride may be a vice of which we are all guilty, but that does not mean that we need to encourage or even excuse it in all its forms, either in ourselves or in others. Though strictly speaking not a fable, this I take to be the moral of Douglass’s thought-provoking book.