To say that people flown with high confidence offer specious things as moral truths is not to say that there are no moral truths there to be known.

The Puzzle of Police Accountability

One of the most vexing questions in the classical liberal tradition has been the issue of official lawlessness. If power tends to corrupt, as Lord Acton warned, what happens when those in authority overstep? This problem is particularly acute in the case of law enforcement, which is literally empowered to use potentially lethal force on civilians. Few questions regarding state authority seem more important—and pressing. Joanna Schwartz examines this question in her new book, Shielded: How the Police Became Untouchable.

Schwartz is a professor of law at UCLA and she draws upon her prior experience as a civil rights litigator to show how the victims of police misconduct are rarely compensated for their injuries. In recent years, Schwartz has published pioneering scholarship, and Shielded offers an accessible overview of that research. She argues that the riots following the police killing of George Floyd in 2020 represented a rebellion against a system that far too often shields police officers, and that many barriers to police accountability remain in place even still. She dispassionately identifies the problems and urges reform.

Before turning to the details of Schwartz’s thesis, it will be useful to briefly review some legal history.

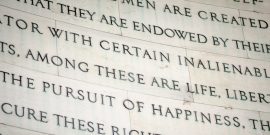

A central tenet of the liberal tradition is the idea that government power must be bounded by law. Magna Carta is celebrated because it represents an early realization of that idea. In the years preceding the American Revolution, the British soldiers involved in the Boston massacre stood trial for murder. It was also widely understood that the King’s men had to respect the rights of the people or they could be sued in the civil courts for monetary damages. When King George III deviated from this legal tradition by transferring such controversies into the admiralty courts and conferring legal immunity on his soldiers, it convinced more and more colonists that further diplomacy with England was futile.

It should also be remembered that illiberal regimes in the world today do not entertain legal complaints against state agents. Iranian police, for example, arrested Mahsa Amini in 2022 for the crime of not wearing a hijab. Protests erupted after she was killed in police custody, but no one expects civil rights lawyers to hale her captors into court to stand trial before an independent jury.

Because the liberal legal order posits the idea of individual rights, it holds itself to different, higher standards. Maintaining such standards requires indefatigable vigilance and perseverance. Enter Schwartz with her bracing thesis that American police are virtually untouchable because of various barriers that have been erected to shield them from liability.

When patrol officers become eligible for promotion to sergeants and lieutenants, misconduct lawsuits often play no part in the evaluation process.

Since the police are rarely prosecuted in the criminal court system, Schwartz argues that civil suits pursuant to the Civil Rights Act of 1871 represent the best hope for victims of police misconduct to find some measure of justice. That law was enacted in the aftermath of the Civil War to help protect the rights of the newly freed slaves. The law allowed complainants to bypass the hostile and racist court system of the South and sue in federal court for impartial adjudication. In legal circles, such lawsuits are known as Section 1983 litigation.

Nowadays, high-profile incidents—especially those caught on tape—pressure mayors into multimillion-dollar settlements, but those cases give the public a misleading impression about Section 1983 litigation more generally. The big payouts are exceptionally rare. The predominant experience is one of defeatism. Aggrieved citizens may have had their homes and belongings ransacked, been humiliated by a roadside strip search, or been beaten up without cause by short-tempered officers. Nothing ever comes of it because civil rights attorneys will decline to take most abuses to court. Even though these attorneys sympathize with the victims, a simple cost-benefit threshold must be met. An attorney must weigh the likelihood of success, and the potential payout, against his or her time investment and the other costs of litigation. According to Schwartz, “Less than 1 percent of people who believe that their rights have been violated by the police ever file a lawsuit.”

After that severe screening process, Section 1983 plaintiffs must overcome a legal doctrine called “qualified immunity.” The Supreme Court has held that attorneys representing police officers can have lawsuits thrown out at an early, pre-trial stage if the law in question had not been “clearly established.” That means victims are stymied when they are unable to find a precedent that exactly matches the circumstances of their police encounter.

To illustrate the legal hair-splitting the courts engage in, Schwartz relates the case of Alexander Baxter. Baxter was a burglary suspect who was seated on the ground, surrendering, with his hands in the air, when the police released their dog to attack him. A previous court had ruled that releasing a dog on a suspect who was simply lying on the ground was unlawful, but no court had yet ruled on a suspect that was in a seated position. Since Baxter’s situation was not yet “clearly established,” the officers were immune, and Baxter’s lawsuit was dismissed during the pre-trial stage.

Schwartz scrutinizes a concern that is often advanced to rationalize strict legal protections for police actions—that it just is not fair to burden these government employees with the risk of personal bankruptcy. If the police fear the loss of their homes and savings accounts, they will probably avoid confrontations and difficult arrest situations. Schwartz patiently demonstrates that such concerns lack merit.

The reality is that when civil suits are filed, municipal attorneys assume control over the cases. They work with attorneys from the local government’s insurer to assess each case and decide whether to fight or settle. In large and mid-sized police departments, the officers themselves are typically unaware that they have been sued and almost never have to pay even a portion of any settlement. Schwartz conducted a study of 80 jurisdictions over six years and found that “local governments almost always pick up the tab.”

More disturbingly, the author found there is little communication between municipal lawyers and police executives. That means when patrol officers become eligible for promotion to sergeants and lieutenants, misconduct lawsuits often play no part in the evaluation process. Schwartz reports several instances where officers were not only not disciplined following illegal actions, but were instead promoted and given the responsibility to train and supervise others. It is a bleak portrait of the system, but accurate.

Although Schwartz does a superb job explaining the pitfalls, both practical and legal, of Section 1983 litigation, her thesis has weaknesses. The book proceeds from the premise that victims of police misconduct are unable to find legal relief in state court. With that path blocked, victims must pursue justice in the federal system. According to Schwartz, civil suits “rarely succeeded when brought in state court under state law.” That is an extraordinarily bold assertion—and it is not seriously defended.

Schwartz is certainly on solid ground when arguing that state courts across the South were “hostile places for Black people,” but beyond that ugly truth, the sweeping claim loses traction. Does she really mean to suggest the state court systems outside the South—courts from Hawaii to Alaska to Ohio to Maine—are also hostile to victims of police misconduct? If so, as the proponent of this claim, she should have offered a more thorough explanation for such a cataclysmic system failure across so many separate legal jurisdictions. Schwartz defaults by leaving this question unaddressed.

Relatedly, there is another omission in Schwartz’s critique of state courts. The author’s premise, as noted above, is that state law is so fraught with barriers that seeking relief there is impracticable—whereas federal court, via Section 1983 lawsuits, is “the best available path toward justice.” One can test that proposition by taking a closer look at federal litigation. After all, if federal court is the more advantageous venue, one would expect Schwartz to bolster her claim by reporting on successful civil lawsuits brought by victims of misconduct against Federal agencies such as the FBI, DEA, and Border Patrol. Schwartz abstains from this line of inquiry.

To win elections, politicians are especially mindful of the interest groups that are closely monitoring their votes in the legislative chamber. With respect to policing, the most formidable special interest groups are the police unions.

A brief examination can provide some context. When federal agents violate the constitutional rights of citizens, a civil lawsuit can be brought against the agents involved. This is commonly referred to as a Bivens action, which is derived from the 1971 Supreme Court case that approved civil suits for damages as a result of unconstitutional conduct. Bivens actions are notoriously difficult to win. In 2021, Appellate Judge Don Willet expressed his dismay with the federal legal precedents in these stark terms: “Private citizens who are brutalized—even killed—by rogue federal officers can find little solace in Bivens.” The fact that plaintiffs are also encountering mountainous obstacles in the federal system undercuts one of the pillars in Schwartz’s storyline.

The final chapter is titled, “A Better Way,” and it is a disappointing close. Here Schwartz ventures into the broader police reform debate, and also discusses political governance more generally. Both the writing and the analysis flag.

The author recounts her experience testifying before legislative committees, and her frustration that elected officials resist her recommendations with unfounded concerns and nostrums. “The key to moving forward,” she writes, is to be “guided by hope instead of fear, by evidence instead of rhetoric.” Schwartz fails her readers with this dewy-eyed call for more courageous and conscientious politicians. Schwartz ought to know that politicians frequently have mixed motives, and use deceptions, double-speak, and hyperbole to rationalize a lot of what they do.

To win elections, politicians are especially mindful of the interest groups that are closely monitoring their votes in the legislative chamber. With respect to policing, the most formidable special interest groups are the police unions. In 2017, the Reuters News Service reported that when budgets get tight and pay raises are impossible, local governments bargain “away the power to discipline police officers, often in closed negotiation meetings with local unions.” Professor Samuel Walker, a widely regarded expert in policing, writes, “Police union contracts contain provisions that impede the effective investigation of reported misconduct and shield officers who are in fact guilty of misconduct from meaningful discipline.”

Police unions are also active during the election season by rewarding politicians with campaign contributions and working to unseat anyone who threatens their agenda. When a city council member in San Antonio proposed to reform the police union contract, the local union targeted her with a $1 million advertising campaign that said she was to blame for the recent spike in city crime. Other members of the city council took note.

Politicians at the national level are also wary of crossing police unions. When President Obama nominated Sonia Sotomayor for a seat on the Supreme Court, then-Vice President Joe Biden gave several speeches to police organizations to reassure them that this judge would “have their back.” And when President Trump was on the campaign trail, he liked to brag that the union of federal immigration and customs agents had given him its endorsement. Suffice it to say that when the national leaders of both parties are seeking their endorsements, the political machinery of police unions is highly developed.

It is more than disappointing that Schwartz barely mentions police unions and the role they play in thwarting reform efforts to increase accountability for officer misconduct. She tiptoes around the proverbial elephant in the room and draws the attention of readers to peripheral topics, such as whether the courts should draw potential jurors from the rolls of licensed drivers instead of from the rolls of registered voters in order to broaden and improve jury pools. Why indulge in such minutiae when most cases (more than 93 percent, according to sources cited by the author) are settled out of court and are not decided by juries?

Shielded is packaged as a work that addresses the myriad ways in which the legal system fails to hold police officers accountable when they break the law. In fact, the book has a narrower focus. It closely examines a single federal statute, Section 1983, a law that is supposed to provide an avenue for victims to sue local police officials and municipalities in federal court for monetary damages and other legal relief. As a primer on Section 1983, the book is a triumph—well-written, informative, and persuasive about many deficiencies that need correction. However, for the reasons mentioned above, the book ebbs in both its introduction and its conclusion—basically the areas in which it strays beyond its core treatment of Section 1983 litigation. For readers interested in a broader examination of police power and legal reform, Shielded should only be considered a valuable starting place.