The first step to restoring moral sobriety in Canada is to stop the deliberate obfuscation of euthanasia records.

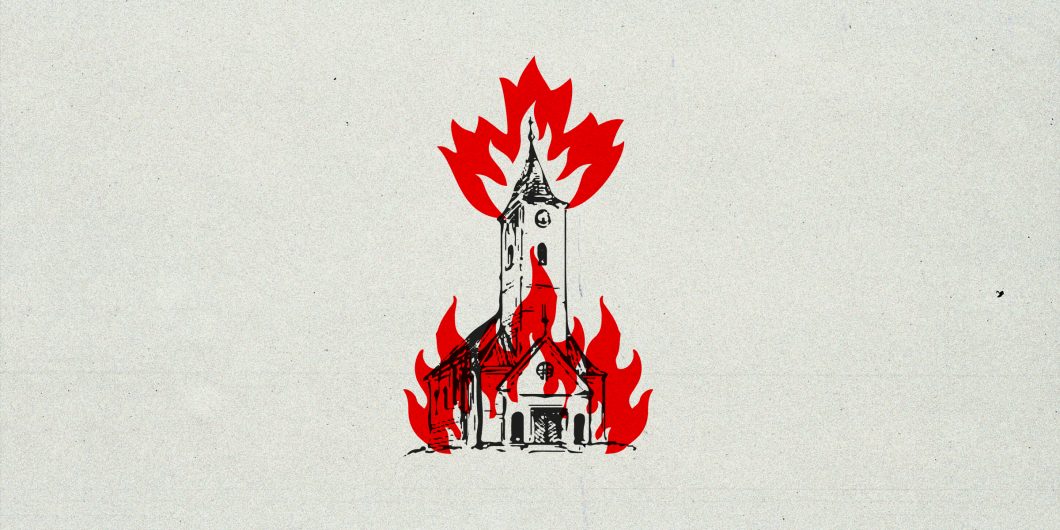

Canada Is on Fire

Since June, more than 60 churches in Canada have been vandalized or burnt. These acts were sparked by the tragic recent discoveries of graves of Indigenous children at the sites of former residential schools. An official policy of the Canadian government, Christian denominations administered these boarding schools for Indigenous children over many decades. The policy, formalized by the federal government in the 1880s, can trace its origins to a school that opened in Ontario in 1831.

At their height in the 1930s, more than 80 residential schools existed in Canada. The federal government took control of all remaining schools from the churches in 1969. The last school closed in the 1990s. Around 150,000 Indigenous children are estimated to have attended the schools.

Indigenous children were often forcibly taken from their families to be enrolled in these schools. They were deculturated within their walls. Many were abused. Scores died. The resulting trauma has haunted survivors and their descendants. Today, Indigenous Canadians suffer disproportionately on most socioeconomic metrics compared to non-Indigenous Canadians. Much remains to be done by governments, churches, and citizens to ease the plight of Indigenous peoples in Canada. The grotesque violations of human rights committed at residential schools, the injustice of creating them, and the catastrophic legacy of this dreadful policy are a national disgrace.

But this disgrace in no way justifies the attacks on churches today. These brazen crimes of intimidation are cause for a national outcry. Yet for the most part, they have been met with muted condemnation from civic leaders, or none at all. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau uttered a few lukewarm sentences of disapproval more than a week after the vandalism began. Since then, crickets.

On social media, many people have rationalized the attacks. Some have applauded them. And a tweet of four words started a saga that signals deep problems within Canada’s social fabric.

On June 30, the executive director of the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association tweeted “Burn it all down” in relation to an article on the burning of churches. Harsha Walia has since resigned, but not apologized. She says the tweet was not literal, but that she referred to dismantling colonial mindsets and structures.

Even so, the inescapable message that her tweet conveyed—burning churches is fine and should continue—is reprehensible coming from the leader of a group that defends civil liberties such as religious freedom. That this basic, straightforward point has been hotly contested on social media is a strong sign that logic, reason, and common sense have taken a backseat in our public discourse.

Some have said that the public criticism of Ms. Walia, a woman of color, largely stems from racism and misogyny. Any reasonable observer would see that the criticism focused on the substance of Ms. Walia’s tweet. If she was the target of bigotry and hatred in the context of private communications, this is despicable. But invoking her identity to distract from the content of her tweet or to discredit her legitimate critics is either a product of ignorance or a tactical ploy.

Others have kept the conversation alive in troubling ways. One law professor mused about the propriety of burning churches. Another called for more of Ms. Walia’s politics, not less.

Imagine how Christian law students might feel sitting in the classrooms of these professors, or how their Christian colleagues might absorb these statements. Today we regularly advocate for safe and inclusive workplaces and learning environments. We validate lived experiences. We laud diversity. Multiculturalism is enshrined in the Canadian Constitution.

If you are not religious, there are probably more Christians than you realize among your acquaintances and friends. The invisibility of their faith and moral convictions is a conscious decision. They fear, with good reason, that disclosing these beliefs will lead to discrimination and ridicule in a variety of settings.

But these tweets suggest that these ideals have more or less traction based on where you sit on the ladder of privilege. The high rung on which Christians are said to sit informs whether their stories deserve to be told. It influences whether their suffering merits sympathy. It is frankly no accident that the Prime Minister has scarcely and tepidly commented on the vandalism of churches. The persecution of the privileged is increasingly viewed as something nobler than persecution.

If you think it is advantageous to publicly profess the tenets and moral teachings of traditional Christianity in Canada today (and in most other Western societies), you are mistaken. If someone is interested in cultivating social influence or personal prestige, these beliefs are far more of a liability than a leg up. It is, seemingly by the day, exponentially more treacherous to take the Christian position in the public square on virtually any issue that animates the so-called culture wars.

If you are not religious, there are probably more Christians than you realize among your acquaintances and friends. The invisibility of their faith and moral convictions is a conscious decision. They fear, with good reason, that disclosing these beliefs will lead to discrimination and ridicule in a variety of settings. I can assure you that those Christian law students will think carefully about how and when they reveal their faith at law school and after. I certainly did. I felt I had to.

Even amid the ashes of burnt churches, it is hard for those who believe that Canada is tainted by systemic injustice perpetuated by the privileged to admit that Christians face tangible adversity today. The privileged, we are told, do not suffer as the unprivileged do—even if the wrongful act is the same. As one person put it, we should not discuss vandalism of churches and vandalism of other places of worship in the same conversation. Why not? Churchgoers are not oppressed.

Speaking of oppression, Christians are called by Christ to lift up the oppressed and downtrodden. They do so in countless ways, noticed or not, every day. There is no doubt that Christians have, time and again, fallen far short of practicing the virtues they preach. But, then again, all of us have.

The attacks on churches have little to do with achieving reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. Many Indigenous leaders and communities in Canada have rightly condemned the attacks. These acts of vandalism and arson are, at their root, modern social justice in action. It is unbecoming of a society that esteems peace, order, and good government.

So too is the broad tenor of the response—or lack thereof—to these acts. The most disturbing part of this episode may be that many Canadians, perhaps most, see no cause for concern. Some even see cause for celebration. Between the indifference and the applause, I am not sure which is worse.

Reconciliation will never come if retribution is in the mix. If Canada wants to remain a civil society, and become a more decent one, this brand of social justice—and the ugly tribalism it breeds—must go.

Otherwise, once the perceived villains of today are gone, who will be next? Who, for that matter, will be last?