The Democratic Congress lost the impeachment fight before it even started.

Could Aaron Burr Have Been Impeached for the Duel?

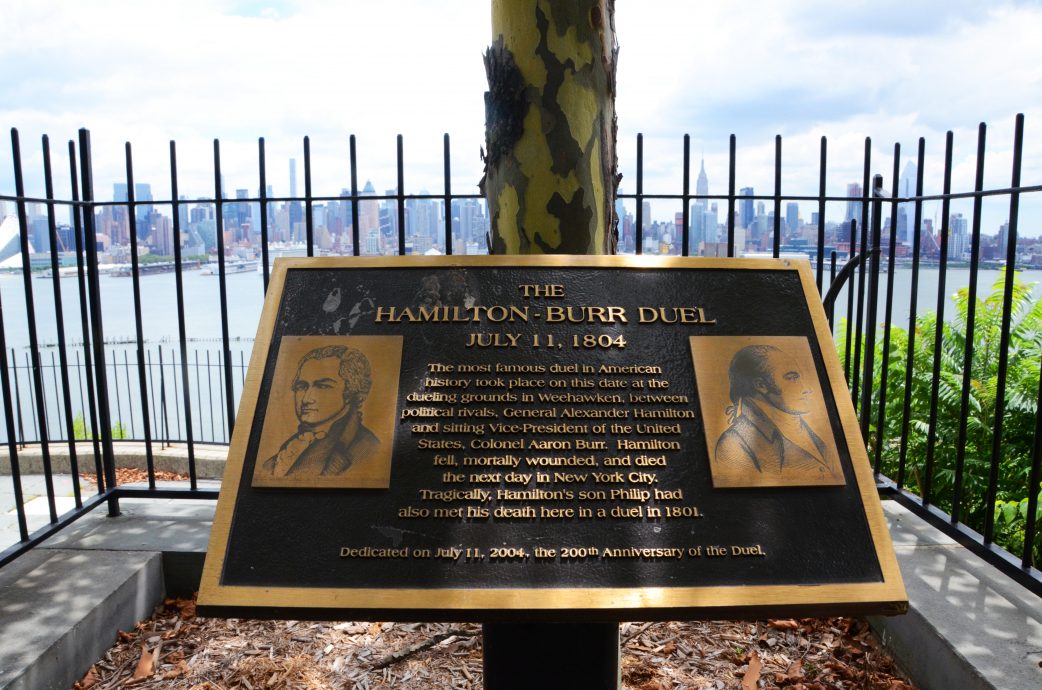

Today, I take a slight detour – but hopefully an interesting one – in my series of posts on the constitutional power of impeachment (prior posts can be found here and here). It is a digression appropriate to this date in history: the anniversary of Aaron Burr’s famous duel with Alexander Hamilton on July 11, 1804. Burr, then the Vice President of the United States, shot and killed Hamilton, the former Secretary of Treasury and his longtime political rival. Hamilton by most accounts deliberately threw away his first shot that morning in Weehawken, New Jersey – across the Hudson River from New York. (Dueling was explicitly a crime in New York.) Burr, however, took deadly aim: his ball mortally wounded Hamilton, who lingered in pain for more than a day before dying at the home of his friend William Bayard in New York the next afternoon. The event is immortalized in history and, more recently, in the hip-hop musical Hamilton.

The question I pose here concerns impeachment: Was Aaron Burr, the Vice President of the United States, constitutionally impeachable for “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” for shooting and killing Alexander Hamilton? The answer, I submit, must be yes. And in that answer lie some potentially interesting lessons for understanding the proper scope of the impeachment power under the U.S. Constitution.

Indeed, the question of Burr’s impeachability embraces several others that frequently arise in discussions of impeachment. Does impeachment reach ordinary criminal-law offenses, if judged to be serious enough acts of wrongdoing? (Yes.) Does impeachment perhaps require commission of a criminal-law offense? (No.) Does impeachment require that the alleged offense have been committed in the officer’s official capacity or have involved misconduct making use specifically of the impeached official’s powers of office – or will a “private capacity” serious wrong suffice? (No official-capacity action is required; so-called “private” crimes can suffice.)

Still more: Can a state indict a federal officer for having committed a state-law criminal offense? (In theory, yes.) Does it matter in this regard whether the alleged offense involves official-capacity conduct? (Yes; a state cannot impair the lawful actions of federal agents or instrumentalities.) Must an officeholder be impeached before he can be indicted or tried for criminal-law offenses? (No, but any criminal-law punishment that effects a practical removal from office – like incarceration and certainly execution – would be a different matter.)

All of these questions are presented, at least implicitly, by the strange case of Aaron Burr. I will elaborate briefly on my answers below, and develop them further at various points later in this series.

A Page of History

But first a little more history: The story of the Burr-Hamilton duel has been well told by others –far better than my brief distillation of it above. For compelling accounts, see Ron Chernow’s magnificent Alexander Hamilton (which served as inspiration for the Broadway show), Thomas Fleming’s Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America, and Joseph Ellis’s Founding Brothers (Chapter Two, entitled “The Duel”).

My interest here is with the legal – and the constitutional – aftermath. Burr was subject to criminal prosecution in both New Jersey and New York, for killing Hamilton. As soon as it became clear that there was a genuine risk that he might be indicted, possibly in both states, Burr fled New York, making his way across the Hudson to New Jersey by boat under cover of night, then continuing on to Philadelphia to wait at the home of a friend for things to cool down. They didn’t – at least not for quite some time. A New York “coroner’s jury” determined Hamilton’s death to be a homicide, the result of Burr’s bullet, and arrest warrants were issued for Burr, and for his second in the duel and Hamilton’s second as accessories. A New York grand jury dropped the murder charge in mid-August and replaced it with the lesser charge of sending a challenge to a duel, a state criminal misdemeanor. New Jersey did not prohibit dueling, but that apparently did not preclude an indictment for murder and Burr was in fact indicted for murder by a New Jersey grand jury in October.

Burr evidently thought Philadelphia too close to the scene of the crime – or to the legal authorities – and decided to take an August tour of South Carolina and Florida before returning to Virginia and eventually Washington, D.C. in the fall to preside over the Senate for his remaining months as Vice President of the United States. His duties included, ironically, presiding over the impeachment trial of Justice Samuel Chase. (More about Burr’s role in the Chase trial presently.)

Jurisdictional and related legal quandaries hampered each state’s criminal cases against Burr. New York prohibited dueling, but the duel occurred in New Jersey. And though the victim of the homicide died in New York, the shot had been fired in New Jersey (which probably accounts for the dropped murder charge in New York). New Jersey had the opposite problems: dueling was not prohibited, making the murder charge there at least somewhat awkward; and Hamilton had died in New York, further complicating matters. And of course Burr all along remained out of the jurisdictional reach of New Jersey and New York courts. Extradition was possible, which might form part of the reason Burr sought to make himself less accessible. It is a nice question whether Burr’s status as Vice President of the United States provided any immunity from state legal process.

Burr sought to get the New Jersey murder charge dismissed – with the (mildly) astonishing support of a cadre of twelve Republican senators who wrote the governor in autumn 1804 to try to get him to terminate the charges against Burr either by pardon or by legislative action. It didn’t work. The New Jersey indictment languished, but was not dropped until three years later, in 1807 – by which time Burr was facing federal criminal charges for treason in connection with his role in a conspiracy to incite a U.S. war with Spain over Mexico, with the aim of detaching several southwestern states from the United States to form a new nation with Britain’s backing.

Now, what about impeachment of Burr, who in 1804 was still Vice President? The Republicans with good reason had dumped Burr from the presidential ticket with Jefferson for 1804, a story ably told elsewhere.

So Burr was a lame-duck Vice President, with just eight months to go in office, when he shot and killed Hamilton. (Burr had also recently been defeated in an attempted run for governor of New York in the spring of 1804.) Lame-duck status would not make Burr unimpeachable, of course, but it helps explain why no effort was made to remove him. Another part of the explanation might be that Burr remained, nominally at least, a Republican. (Burr bounced all over the place, supporting whichever party might better support him.) The Republicans had substantial majorities in the House and Senate and might have been disinclined to support the inconvenient and embarrassing impeachment of a Vice President formally allied with their own party, especially since he would soon be out in any event. Recall also that a dozen Republican senators were on record as calling for dismissal of the state criminal charges pending against Burr. Some Republicans might have thought the charges lacked merit. Others might have been willing to overlook Burr’s misdeed, given the context of the duel, or the fact that the opponent was Hamilton. (Some Federalists at the time thought – and some historians today appear to agree – that the Jeffersonian Republicans were not all that upset with Burr for killing Hamilton, their longtime arch-Federalist nemesis.)

Congressional Republicans had other fish to fry: they needed Burr to preside over the pending impeachment trial of Samuel Chase, a rabidly partisan, hated Federalist Supreme Court justice. Some Republicans believed – probably wrongly – that Burr might prove of considerable usefulness to them as presiding officer over Chase’s trial.

For whatever reason, President Jefferson, who had not previously displayed warm hospitality toward his vice president, hosted Burr for dinner twice upon Burr’s return to Washington following the duel and before the Chase trial. Burr was also welcomed back with unaccustomed cordiality by cabinet members James Madison and Albert Gallatin – entreaties the sincerity of which we know Burr doubted because of private correspondence.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that low politics and soft pragmatism – expedience, not high-minded constitutional principle – lay behind the lack of effort to impeach Aaron Burr.

Historical Description, Constitutional Prescription

A partisan lack of appetite for impeachment, for reasons of expediency or worse, does not answer the question whether there were legitimate constitutional grounds for impeachment. On that question, the answer seems to me quite clear: a high government official’s deliberate act of shooting at, and killing, another person, without legal justification – whether in the course of a duel or not – constitutes an offense for which the House and Senate rightfully could impeach and convict that official.

The power of impeachment, given the breadth of offenses it can encompass, invariably admits of a range of judgment as to how it applies to particular situations. There is perhaps – perhaps – some minuscule room for disagreement as to whether Burr’s conduct actually merited impeachment or whether the circumstances necessitated that remedy, given Burr’s few remaining months in office.

But as to the pure constitutional question of whether the impeachment of Vice President Aaron Burr, for killing Alexander Hamilton, would have fit within the range of meaning of the Constitution’s broadly worded standard authorizing impeachment of federal civil officers for “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors,” the answer would seem to be self-evident: it would. As for the judgment whether impeachment was appropriate for Burr under the circumstances, count me among those who would consider it worth the effort. The example of a murderous vice president remaining in office – and even presiding over a judicial impeachment trial! – is worth avoiding at all hazards. The harm outlasts the miscreant’s term of office and does not expire with it.

In their recent book on impeachment, Laurence Tribe and Joshua Matz briefly discuss the case, offering the strange suggestion that the Burr experience constitutes some sort of constitutional precedent for the proposition that “not all crimes by federal officials have been seen as impeachable.” (44). In contrast (if not contradiction), they argue that if Vice President Mike Pence were today to shoot and kill Treasury Secretary Mnuchin, “he would surely be impeached, removed from office, and charged with murder.” Why the one case should be thought uncertain and the other easy-as-pie straightforward is unclear. As a matter of principle they are surely identical.

The explanation may lie in the effort to reconcile, or adjust, past statements to present reality. Twenty years ago, when Bill Clinton’s impeachability was the issue du jour, Professor Tribe had invoked the Burr case to illustrate the claim that criminality – even the commission of a serious felony, if a “private” criminal offense that did not involve the use of official position – did not necessarily mean the official could properly be subjected to impeachment. That position served Tribe’s argument before Congress against the impeachability of Clinton for the (supposedly) “private” crimes of perjury and obstruction of justice committed while Clinton was president. The new book clings to that position, labeling the impeachment of Clinton “contemptible” and motivated by “partisan animus.” Perhaps the book’s passage on Burr is a bow to the reality of Tribe’s previously stated views and a gentle attempt to soften them going forward.

The Pence-shooting-Mnuchin-is-impeachable position is the one that makes sense. The Burr-shooting-Hamilton-might-not-be-impeachable position does not. The implications of the Burr example (and Pence hypothetical) seem clear for the propriety of Clinton’s impeachment – which of course is exactly the problem for Tribe’s position. Perjury and obstruction of justice are serious felonies (even if somehow cast as “private-capacity” wrongs). They are not quite like gunning down a man, but they are serious wrongs against the public and the administration of justice. If Burr was properly impeachable, so was Clinton.

Some Implications

What, then, of the series of questions I posed at the outset concerning constitutional issues implicated by the prospect of impeaching Aaron Burr? Let me briefly elaborate on my quick answers above.

First, the power of impeachment plainly extends to ordinary criminal-law offenses, if judged to be serious enough acts of wrongdoing. Though it is clear as a matter of original meaning that an impeachable offense need not be a literal criminal-law violation – a point I will develop in later posts – it is equally plain that an impeachable offense might well be an ordinary crime, too.

The text of the Impeachment-Punishment clause of Article I, Section 3 assumes this possibility (emphasis added):

Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust, or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment, and Punishment, according to Law.

In Federalist 65, Hamilton made the same point: “the punishment which may be the consequence of conviction upon impeachment is not to terminate the chastisement of the offender embraced” who “will still be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.” Regular crimes can count as impeachable offenses.

Second, it would not seem to matter in the slightest whether the action was done in any “official-capacity” sense or using the “powers or position of office.” Murder is murder. Purely “private-capacity,” non-office-holding-specific misconduct surely can suffice, as the murder example aptly illustrates. If the wrongdoing is judged to be bad enough, it need not have anything to do with the use of the powers, privileges, or prerogatives of office in its commission. Burr’s killing of Hamilton had nothing to do with Burr’s vice presidential duties, for sure; but that should not foreclose his impeachability, if otherwise warranted by the seriousness of the offense committed.

Consider another example. History’s other leading candidate for a vice presidential impeachment is Spiro Agnew, Richard Nixon’s first vice president. Agnew resigned the vice presidency in 1973 and later pled no contest (guilty, but without a formal admission) to federal bribery charges arising from conduct occurring while Agnew was governor of Maryland. Could Agnew have been impeached on the basis of criminal conduct having nothing at all to do with his actions as vice president – actions that both occurred before he even held any federal elective office and that involved no federal-capacity wrong? The intuitive answer is of course yes. Can one imagine the chutzpah of Agnew defending against his impeachment on the grounds that he had committed no offense as vice president – that he might be a criminal but it was only by virtue of things he had done as governor, and surely he wasn’t constitutionally impeachable for that!

Next question: Does impeachment require a prior criminal conviction, or at least an indictment? Clearly not – not only does an impeachable offense not need to have been a criminal act at all, it need not have been a criminal act proven to be such in a prior proceeding in a court of law. Congress does not need to await a criminal indictment in order to proceed with an impeachment. The House could have impeached, and the Senate convicted, Aaron Burr of killing Alexander Hamilton, with or without any criminal indictment by New Jersey or New York. Congress likewise could have impeached Agnew for receipt of bribes as Governor of Maryland, whether or not criminal proceedings had begun or were even contemplated.

The reverse holds true as well: Congress in theory could decline to impeach and remove from federal office a proven-guilty criminal. That raises an interesting question of its own: Must an officeholder be impeached before he can be prosecuted for criminal-law offenses? Because of its importance (and possible contemporary relevance), I will address this issue on its own in a subsequent post.

For now, I suggest that the answer is a bit complicated: Holding federal office does not itself confer immunity from state criminal proceedings concerning (non-official) criminal conduct in which an officer may have engaged. (Authorized, federal official conduct is different – but that certainly was not Aaron Burr’s case.) Even the President is not entirely immune from compulsory legal process, as the Supreme Court’s decision in the Nixon Tapes Case and in the Paula Jones case attest. However, to the extent conviction resulting in a prison sentence would work a de facto removal from office, I believe impeachment must precede incarceration. It follows, I think, that New Jersey and New York could indict, try, and even convict Burr for state-law crimes. But they could not place him behind bars – or execute him – until after he left office.

One final lesson arising from the prospect of impeaching Aaron Burr: What about ordinary partisan political considerations? Do such factors ever properly supply a basis for resisting an otherwise justified impeachment? Is political support for a person of one’s own political party, or the political embarrassment or inconvenience occasioned by impeachment, a legitimate basis for declining to support an otherwise merited impeachment? Is the political usefulness of such a person for other partisan or policy purposes (like Burr’s presiding over Chase’s impeachment) a reason to preserve an otherwise impeachable scoundrel in his office?

Burr makes an interesting “test case” for thinking about the relevance (or not) of such considerations. Such factors obviously have arisen, and will continue to arise, in many other impeachment situations to varying degrees. What one thinks about such factors in the case of Burr ought to guide one’s thinking on the same questions with respect to other impeachments. Clear thinking about the strange case of Aaron Burr might help produce clear thinking about impeachment generally.