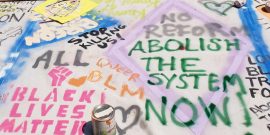

Critical Theory, and now Critical Race Theory, are fully-loaded howitzers aimed at all the pillars of the system.

Court Politics

Several weeks ago, the Milwaukee Bucks of the NBA boycotted their scheduled first-round playoff game versus the Orlando Magic after a police officer shot an African American man seven times in the back. The police were on the scene after having been called by a woman who accused the man of sexually assaulting her and violating a restraining order. Setting aside the specifics of the incident, which are still murky, the NBA and its players pondered canceling the remainder of their already abbreviated playoffs in their continuing efforts to draw attention to the widely held view that African Americans are frequently the targets of police harassment and brutality. Ultimately cooler heads and accountants prevailed, and the playoffs are now continuing. However, the league is battling declining television ratings and revenue losses from having no fans in the stands. Whether the COVID pandemic or the increased spotlight the league is putting on social justice issues is having the more consequential effect on its bottom line is not clear.

Various contemporary commentators have been bemoaning what they view as the increasing “politicization” of sports in recent years. Most point to Colin Kaepernick’s decision to begin kneeling during the national anthem as a protest against what he and others believed was the unfair treatment of African Americans in the US as the starting point of this injection of social and political issues into the professional sports world. You don’t have to look back far to see that sports and politics have been intertwined for much of the 20th century. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t something different about today’s athlete-activists.

Politicized Sports, Past and Present

In 1967, during the height of the Vietnam War, then heavyweight champion of the world Muhammad Ali was arrested, although never imprisoned, for refusing to serve in the military, claiming that his religious beliefs prevented him from joining and aiding in a war. Ali would not be allowed to fight for more than three years and arguably lost the prime of his fighting career and untold millions in income. While he gained immeasurably in social and political standing as a result of his decision, Ali was ostracized, harassed by the FBI, and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees trying to stay out of jail and get his boxing license reinstated.

Before Ali, of course, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball and faced harsh reactions from many white players and fans. Jesse Owens, who suffered throughout his life from racism in the U.S. was a hero in the 1936 Olympics as a symbol of opposition to Nazism. And there are many other examples of individuals we now view with admiration standing up for principles we now largely accept—that there should be no legal barrier against individuals having access to pursue the lives they wish to lead because of their race or ethnicity. So in some ways, the idea that combining politics and sports is a “new” phenomenon is wrong.

However, we have to ask how these previous examples of political activism compare to the actions that a group of highly paid professional athletes is taking today. Refusing to play in reaction to a news item, even one that seems to fit into our national conversation about a widely perceived problem, seems to be very different from what Owens, Robinson, and even Ali did. Like the pioneers who came before them, these players are no doubt trying, to the best of their abilities, to play a role in stopping what they believe is unfair treatment. But unlike the political and social context that Owens, Robinson, and Ali faced, African Americans are no longer legally prevented from doing anything. Other less obvious barriers that minorities face in everyday life no doubt exist and need to be taken seriously in policy discussions. But those policy areas are not as pervasive or burdensome as segregation and Jim Crow. The word “systemic” is commonly used today, but no contemporary racial problem comes close to being as systemic as the barriers faced by mid-century black athletes.

Moreover, the solutions to today’s problems are not as black and white as they were in the previous century. Police reform is about as gray as a battleship when compared to the stark moral lines of Jim Crow. It raises important issues for minorities who don’t get good policing but who have also typically aligned themselves with a political party, the Democrats, who support public sector unions— a major obstacle to police reform. I think we can all agree that the police should not be killing people by choking them as they beg to be released. However, it is not clear what structural reforms are needed to improve the safety of African Americans and give them fuller access to the economic, political, and social aspects of American life. Nor is it clear how to achieve them. Such complicated questions cannot be boiled down to simple slogans on the back of jerseys.

Furthermore, unlike athletes in the 20th century, today’s athletes are paid handsomely for their performance through the revenue generated from ticket sales, television contracts, merchandise sales, and various other ways public figures make money. It’s a multi-billion dollar industry and one that was growing substantially prior to the COVID outbreak. Franchise values across all sports are in the billions, league revenues have exploded, and player salaries have correspondingly grown into the hundreds of millions for the best players in various professional sports. African Americans and Latinos make up a large percentage of professional athletes in some of the most popular American sports including baseball, football, and basketball. With that kind of wealth and representation, athletes do not generate wide sympathy across the US population, particularly one that has just suffered massive unemployment in the wake of the government’s decision to lock down our economy in the wake of COVID.

Sports, Activism, and Success

Sports have undoubtedly helped to uplift African Americans in the US and elsewhere. But once the formal color barrier was broken, athletes like Ali, Kaepernick, and others seem to represent a different approach to the politicization of sports. As an athlete, Ali followed in the footsteps of Joe Louis, who was the first African American heavyweight champion of the world. Louis broke down barriers because he was successful and non-political, in much the same way Louis Armstrong and Nat King Cole were in the entertainment world. They made money, were popular among white and black audiences, and didn’t overtly challenge conventional white notions of how society should be.

I have no interest in listening to the simplified slogans of athletes or entertainers on political matters. I also wouldn’t go to an attorney for dental work.

Ali was not Louis Armstrong or Joe Louis. Ali belonged to the Nation of Islam. He spoke openly and provocatively about racism. He was friends with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, both of whom would be assassinated for political reasons. He made comments about race relations, often incendiary ones about whites, and attacked his black opponents whom he called “Uncle Toms” and other derogatory terms. He used such language with Joe Frazier before the first of their famous battles in 1971.

Now in boxing, drawing attention to the fight with conflict and personal attacks is part of the business. To the extent that Ali was a showman and a political figure, he regularly and freely crossed back and forth between the two venues. And even though he wasn’t the best businessperson in the world, he became famous and relatively wealthy. He helped lay the foundation for Michael Jordan, LeBron James, and other African American athletes who were accepted both as athletes and public figures—people who could endorse mainstream products and reap the rewards.

Kaepernick is more like the early Ali—clearly a more political figure, but one who is not uninterested in money. Ali made and lost fortunes during his early years in boxing while he was engaged in political activity. Kaepernick, shunned unfairly by the NFL, turned to social justice not only as a cause but also a vocation. Kaepernick signed a reportedly very lucrative Nike contract, along with several other prominent African American athletes as part of the company’s attempt to market itself as not merely an athletic wear company, but one that supports social justice. (Imagine a hiking company that supports environmental causes: Companies, athletes, and agents understand that branding matters.)

However, this move into politics is not without risks to the economics of sports. While Ali drew eyes to his fights as the controversial firebrand of the new, young African American taking on white America, it is easy to forget that he also alienated many fans. While Kaepernick is clearly popular among a segment of the population, he is regularly the target of conservative attacks and criticism. In the case of the NBA, all one has to do is look at the league’s embarrassing messaging disaster regarding China late in 2019 in which current social justice warriors, like LeBron James, rejected the idea that they ought to criticize China’s appalling human rights record because it is a country in which their personally branded merchandise sold for millions.

No one is looking for a lecture

The move to engage in the politics of international relations or policing is a very different, and much more complicated, kettle of fish than arguing that individuals should not be excluded from participating in sports because of their race or ethnicity. The idea that Jackie Robinson couldn’t play baseball because he was black presented a simple question to Americans, and one they ultimately got right. Ali presented a less obvious challenge when he argued that blacks, although more widely accepted than they had been, were still fighting for equality in the South and access to housing and schools and jobs from which they were largely excluded.

That’s very, very different than getting caught up with how the US and China should maintain economic and political relations. It may be more similar to debates over policing. However, the fundamental changes needed to truly reform the police—most notably the removal of qualified immunity for police officers, efforts to restructure policing locally, and limitations on the power of public sector police unions—are a can of poisonous snakes for those on the left who reflexively defend Kaepernick and Black Lives Matter.

To be clear, I am not saying BLM or Kaepernick are necessarily wrong. We do need to engage in serious and civil discussions about policing, and we have needed to do so for decades. However, as someone who has discussed police reforms publicly, I simply have no interest in listening to the simplified slogans of athletes or entertainers on these matters, and many people likely feel the same way. I also wouldn’t go to an attorney for dental work. Attorneys, dentists, NBA players, and actors are free to have political opinions, but those opinions never convince me to use their services. I go to them because of the jobs they do for me in a market. Their professional success in basketball, football, the law, or dentistry, regardless of their political views, race, ethnicity, or creed is the key issue for me.

I cannot begin to imagine the pressure or expectations that young, successful, prominent minorities feel to serve as role models for their communities. I commend them for doing what they believe is right. They are as free to make their actions “political” as they see fit. However, they and their supporters must recognize that in any reasonable liberal order, citizens and consumers of the entertainment/sports world are free to spend their dollars in venues that do not inject politics into the medium. If Colin Kaepernick or LeBron James wants to discuss the specifics of truly reforming the police, advancing the interests of minorities through market participation, and finding new and innovative alternatives to existing policies, rather than waving banners and relying on simple slogans, I and many others are ready to talk about that in appropriate political forums. But they seem uninterested in such a conversation and are benefitting quite handsomely from their pursuits. Good for them, but in a society highly polarized and fraught with angry simplistic language and slogans, I for one don’t need another lecture. I need a break from it all.