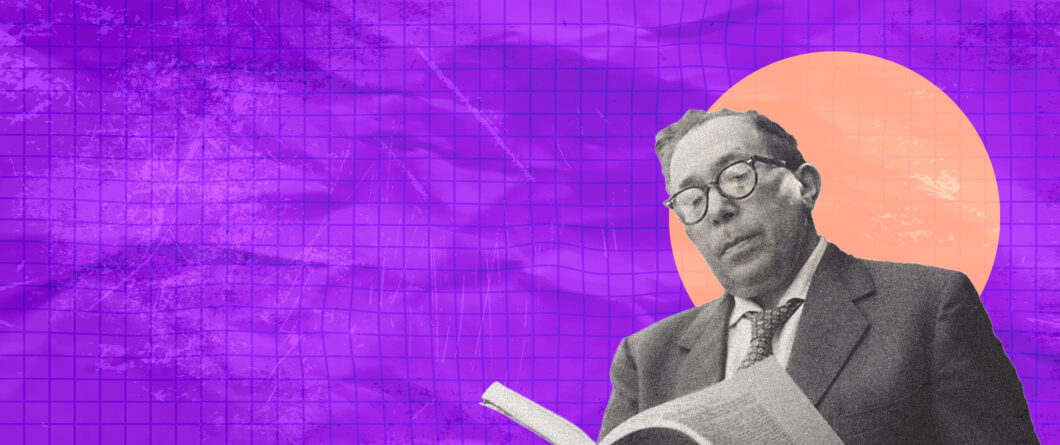

The year 2023 witnessed two significant anniversaries related to the life and thought of the political philosopher Leo Strauss: the 70th anniversary of the publication of his best-known and most synoptic work, Natural Right and History (1953), and the 50th anniversary of his death in 1973. A figure of controversy in his life, Strauss and his students (so-called “Straussians”) remain polarizing today.

On the one hand, left-wing academics and the journalists who endlessly recirculate clichés and terrible simplifications see in Strauss-influenced scholars an elitist and anti-democratic cabal; those political theorists, not few in number, who specialize in reducing thinkers to the commonplace categories of their age mock the Straussian claim that the thought that informs the Great Books has transhistorical significance. On the other hand, some conservatives and people of faith see in Strauss’s approach a barely concealed Averroism that reduces religion to a useful tool for encouraging self-restraint among ordinary souls and a mere simulacra of deeper philosophical truths. One could multiply the criticisms and indictments, some more strident than others but few characterized by a serious effort to understand Strauss as he understood himself. In addition, most critics of Strauss and Straussians assume a uniformity in the Straussian world that simply doesn’t exist and never really has.

Let us, then, approach Strauss’s thought and legacy with unfeigned respect and a determined effort to do it justice. Strauss, a German Jew who took refuge in the United States to escape the barbarous ideological despotism that had overtaken his homeland, was an honorable man and an anti-totalitarian thinker through and through. He was a penetrating critic of what he called “the universal and homogeneous state.” He despised Nazism and Communism and came to have deep respect for the moderation and good sense that still informed liberal democracy of the Anglo-American sort in the middle of the twentieth century. In his 1965 essay, “The Three Waves of Modernity,” Strauss insisted that the “crisis of our time,” the inability of modern reason to defend itself adequately against “historicist” critiques of it lodged by the likes of Rousseau and Nietzsche, did not necessarily imply a “practical crisis” since “the superiority of liberal democracy to communism, Stalinist or post-Stalinist, [was] obvious enough.” But Strauss also appreciated that, at the time of the writing of that essay, liberal democracy still drew “powerful support from a way of thinking that cannot be called modern at all: the premodern thought of our Western tradition.” That tradition reminded modern men and women that rights must be accompanied by duties, that the pursuit of petty and paltry pleasures does not exhaust the life of the soul, and that the recognition of the non-arbitrary distinction between right and wrong, good and evil, was crucial to a life well lived. That premodern tradition still had an ample place for heroes and saints.

That does not mean that our task was simply to receive that tradition—we had to carry it on and renew it. In a 1962 essay, “Liberal Education and Responsibility” (like “The Three Waves of Modernity” it can be found in Hilail Gildin’s An Introduction to Political Philosophy: Ten Essays by Leo Strauss), Strauss stressed the need to quietly cultivate a liberally educated “aristocracy” within mass society, to use the freedoms made possible by modern democracy to cultivate human excellence through the study of the Great Books. Such “outposts” of human excellence, as Strauss called them, “may come to be regarded by many citizens as salutary to the republic and as deserving of giving to it its tone.” From the “grandiose failures of Marx and Nietzsche,” “the father of communism” and “the stepgrandfather of fascism,” respectively, Strauss drew this important conclusion: “wisdom cannot be separated from moderation and hence [the need] to understand that wisdom requires unhesitating loyalty to a decent constitution and even to the cause of constitutionalism.” It would be hard to surpass in eloquence or wisdom Strauss’s oft-cited remark that such moderation “will protect us against the twin dangers of visionary expectations from politics and unmanly contempt” for it. This, of course, was a classical moderation, not to be confused with the slow-motion accommodation to the zeitgeist proposed by some, then and now. Strauss wanted the liberally educated to remain committed to practical moderation and to cultivate the high-minded prudence of the responsible citizen and statesman. All of this is admirable and, in today’s context, profoundly countercultural.

Strauss’s respectful but hard-hitting critique of the “fact-value” distinction articulated by the great German social scientist Max Weber allowed me as a young man to more fully appreciate how crucial discerning moral evaluation is to seeing things as they are.

When I first read Natural Right and History as a graduate student in the early 1980s, I was won over by the mixture of wisdom and spirited solicitude for Western civilization that seemed to mark the book from beginning to end. Strauss pointedly took aim at facile relativism and the thoughtless denial of natural right that were typical of the most influential currents of modern philosophy and social science. Without being openly or obviously religious, he had every confidence that reason could adjudicate between thoughtless hedonism and “spurious enthusiasms” on the one hand, and “the ways of life recommended by Amos or Socrates” on the other. He freely evoked such uplifting and ennobling categories as “eternity” and “transcendence” (even if in a more specifically philosophical idiom) and feared that the abandonment of the quest for the “best regime” and the best way of life would undermine the human capacities to cultivate the soul and “transcend the actual.” Human beings could become too at home in this world, he feared.

Strauss’s respectful but hard-hitting critique of the “fact-value” distinction articulated by the great German social scientist Max Weber allowed me as a young man to more fully appreciate how crucial discerning moral evaluation is to seeing things as they are. Such calibrated moral evaluation is integral to social science (and political philosophy), rightly understood. Among other things, Strauss brilliantly pointed out that, and how, Weber departed from his own theory: “His work would be not merely dull but absolutely meaningless if he did not speak almost constantly of practically all intellectual and moral virtues and vices in the appropriate language, i.e. in the language of praise and blame.” A striking discussion in Natural Right and History observed that “the prohibition against value judgments in social science” would allow one to speak about everything relevant to a concentration camp except the most pertinent thing: “we would not be permitted to speak of cruelty.” Such a methodologically neutered description would turn out to be an unintended, biting satire—a powerful indictment of the social science enterprise founded on it.

Statesmanship

Even Strauss’s famous eulogy for Winston Churchill, delivered in class at the University of Chicago on January 25, 1965, unfolds as part of a larger critique of the intellectual and moral obtuseness underlying the fact-value distinction, the arbitrary separation of factual description from moral judgment, a point ably made by Timothy W. Burns in his recent book on Strauss. Strauss admired Churchill, the “indomitable and magnanimous statesman” as he called him, both for his heroic struggle against Hitler (“the insane tyrant”) and Hitlerism and for his ample cognizance of the “threat to freedom which [was] posed by Stalin and his successors.” “Not a whit less important than his deeds and speeches,” however, “are his writings, above all his Marlborough, the greatest historical work written in our century, an inexhaustible mine of political wisdom or understanding, which should be required reading for every student of political science.” Here the magnanimous statesman contributes mightily to authentic understanding.

On this occasion, Strauss honored Churchill’s greatness with rare discernment and eloquence. The ennobling example of Churchill, Strauss insisted, should remind every student of political things that “we must train ourselves and others in seeing things as they are, and this means above all in seeing their greatness and their misery, their excellence and their vileness, their nobility and their triumphs, and therefore never to mistake mediocrity, however brilliant, for true greatness.” To carry out this essential duty, students of politics must “liberate” themselves “from the supposition that value statements cannot be factual statements.” Strauss’s beautiful tribute to Churchill was thus part and parcel of his larger “phenomenological” recovery of the language of praise and blame at the service of understanding moral and political things as they are in all “their greatness and misery.” The evocation of Pascal’s Pensées is clearly self-conscious and helps add spiritual depth to the welcome and necessary recovery of Aristotelian common sense.

Strauss affirms that there is such a thing as the “disinterested” admiration of human excellence.

The case of Edmund Burke, another great statesman whom Strauss admired, is more complex. Strauss’s colleague at the New School for Social Research, Erich Hula, testified that during World War II, Strauss regularly cited and drew upon the wisdom and the inspiring rhetoric of both Burke and Churchill, and did so enthusiastically. In Natural Right and History, Strauss cites Burke to highlight the disturbing character of modern “political atheism and political hedonism,” which in contrast to most forms of premodern atheism, was “active, designing, turbulent, and seditious” (in Burke’s striking words). With Burke, he saw the fanaticism inherent in the French revolutionaries’ one-sided emphasis on “humanity and benevolence” as opposed to “that class of virtues that restrain the appetite.” With Burke, Strauss appreciated that “the extreme humanitarianism of the theorists of the French Revolution necessarily leads to bestiality.”

Strauss also admired Burke’s return to Cicero and Suarez, to “the authors of sound antiquity.” But Strauss worried that Burke’s sharp “distinction between theory and practice,” his otherwise admirable recovery of prudence, “the god of this lower world,” ended up breaking with the classical or Aristotelian subordination of sound practice, however laudable, to contemplative theory. Citing a near despairing passage from Burke about the possibility that Providence might have decreed or allowed the victory of the French Revolution, one passage in a truly voluminous corpus, Strauss states that Burke, at least in this passage, is “oblivious of the nobility of last-ditch resistance to the enemies of mankind, ‘going down with guns blazing and flags flying’”. Yet earlier Strauss had lauded Burke for his courageous and unhesitating resistance to the French Revolution, “a revolution in the minds of men,” that the Anglo-Irish statesman regarded as “thoroughly evil.” Burke was the “last ditch resistance” to the Jacobin scourge as Strauss had acknowledged just a few pages before.

Strauss ends this perplexing chapter on a note of praise: “Burke himself was still too deeply imbued with the spirit of ‘sound antiquity’ to allow the concern with individuality to overpower the concern with virtue.” Yet, too many people, friends and foes alike, come away from reading the Burke chapter in Natural Right and History convinced that Strauss was merely a critic of Burke. That is far from the truth, as my summary aims to suggest.

Right by Nature

In the core chapters of Natural Right and History, Strauss provides a rich and evocative account of those elementary human experiences that give rise to the recognition that some things are “right by nature.” The book begins with an epigram drawn from the Book of Kings about the poor man whose beloved sheep was taken from him by a rich man who had an abundant flock and herd, as well as the refusal of Naboth the Jezreelite to give Ahab king of Samaria his ancestral inheritance of land because the grasping king demands it. In both these cases, it is not very difficult for a morally alert human being to distinguish right from wrong.

In the chapters on “The Origin of Natural Right” and “Classical Natural Right” Strauss affirms that there is such a thing as the “disinterested” admiration of human excellence. This in and of itself provides powerful evidence for the reality of “natural right.” Following Plato and Aristotle, Strauss provides a lucid description of “man’s natural constitution” rooted in the distinction between the body and the soul and the recognition that “the soul stands higher than the body.” Such an account of the soul naturally leads one to recognize that “the proper work of man lies in living thoughtfully, in understanding, and in thoughtful action.” Strauss is no conventionalist or relativist. He readily affirms that “the good life…flows from a well-ordered or healthy soul.” Strauss identified the good life not with the life of pleasure (although pleasures accompanied it, including the “serenity” he sometimes attributed to Socrates) but with “the life of excellence or virtue.” But in at least one dramatic point in Natural Right and History Strauss identified the merely moral life as “vulgar,” even “mutilated.” This is undoubtedly a “hard saying,” a jarring affirmation. Are only philosophers truly human? That strikes this reader as a bridge too far. What begins as a dialectical account of the ascent of the soul, ends up undercutting its indispensable beginnings. This is a problem we will return to in the course of our discussion.

I think it is a safer bet not to extrapolate from one or two more “extreme” statements of Strauss and draw a questionable “esoteric” account of his ”ultimate” convictions. I’m inclined to agree with Catherine and Michel Zuckert that Strauss himself wrote quite carefully (with prudent “pedagogic reserve” when appropriate) but not esoterically. There is no “secret teaching,” no code to be deciphered. More importantly, Strauss’s thought, like the classical wisdom it draws upon, is riven with tensions, many of them salutary and productive. There is no doubt that Strauss aimed to recover the dignity and rarity of philosophy as a comprehensive “way of life” (and not a mere academic pursuit) driven by the pursuit of truth informed by intellectual eros, “nature’s grace” as he called it. Strauss sometimes reified this activity with talk about the philosopher, the rarest and highest human type, who nonetheless somehow remained a human being. In his 1948 address on “Reason and Revelation” at Hartford Theological Seminary, Strauss argued that Pascal was not wrong when he spoke about “the misery of man without God” except for one and only one exception: The Socratic philosopher who is serene in his search for truth without the consolation of faith in the gods or Divine Providence. More rarely, Strauss would speak of the “probity” of the philosopher who knows that even the earth will perish and that the good is not ultimately supported. Strauss in this voice seemed to believe with Ernest Renan that “the truth is sad,” at least in the final respect. There is dogmatism lurking in this alleged intellectual probity, however, a bias in favor of atheism, one might say. But, as Harry Jaffa pointed out in a 1982 article in Modern Age, in the final pages of Thoughts on Machiavelli (1958), Strauss called for a deepened appreciation of the old and ennobling idea of the “primacy of the Good,” a thought and affirmation that point in a rather different direction from the sad probity of the philosopher.

I remain most indebted to the Strauss who upended modern reductionism and recovered the dignity of the Lebenswelt, the common world where good and evil, the noble and base, and reasonable moral and political judgment, first come to sight.

In any case, tensions abound in Strauss’s admirable efforts to recover a transhistorical conception of philosophizing and a genuine openness to the intimations of natural justice that are evident in our common life or common world. In his role as a philosophical phenomenologist, so to speak, Strauss argued that “man’s freedom is accompanied by a sacred awe, by a divination that not everything is permitted. We may call this awe-inspired fear ‘man’s natural conscience.’ Restraint is therefore as natural or as primeval as freedom.” Likewise, in his profound essay on “German Nihilism” delivered to a seminar at the New School for Social Research” in 1941 and published posthumously many years later, Strauss suggested that the twin pillars of civilization (defined as “the conscious culture of humanity”) are “morals and science, both united.” In a particularly suggestive formulation, Strauss argues that “science without morals degenerates into cynicism, and thus destroys the basis of the scientific effort itself; and morals without science degenerates into superstition and thus is apt to become fanatic cruelty.”

In his excellent recent book, Leo Strauss on Democracy, Technology, and Liberal Education (which intelligently discusses many of these matters under consideration), my friend Timothy W. Burns identifies science with “theoretical reasoning” and morals with “practical reasoning.” So far, so good. But following an occasional line of thought in Strauss, Burns identifies philosophy or “theoretical reasoning” with “resigned contemplation of necessities or causes,” and the West’s religious and moral traditions, especially biblical wisdom, with a practical perspective that is non-philosophical. Burns argues that philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle, and Strauss himself, “offered their limited guidance” to sound practice only when “looking at things as the statesman does.” As Burns rightly points out, they did so generously and humanely. But isn’t the “truth of practice,” as Catherine and Michael Zuckert have called it, something that theoretical reasoning must also acknowledge in a truly substantial way, “theoretically” as well as practically? Perhaps Strauss can pay tribute to the “beautiful principles of justice,” as he once called them, precisely because he, too, must finally bow before man’s “natural conscience” as a datum of profound relevance to theory and practice alike, and to every decent and self-respecting human being, including the philosopher.

I admire Strauss as much as I did when I first started to grapple with his thought in my early to mid-twenties. But I am now more sensitive to the tensions inherent in his recovery of classical political philosophy. With the Socratic Cicero (see Book 5 of Tusculan Disputations), I am more hesitant to reduce “wisdom” (Cicero’s word of choice) capaciously understood with the philosopher per se. I am particularly wary of the quest for “pure reason” which readily gives way to the spirit of abstraction. There is something too narrow, austere, even “inhuman” about the reified philosopher that many Straussians appeal to. Moreover, reason belongs to religion, too, and the evidence for its truth can be found in the profound longings of the human soul as much as in the “brute fact of revelation,” as Strauss claimed. Biblical religion puts forward a compelling philosophical anthropology that wrestles with the drama of good and evil in the human soul in ways that strikingly capture the “truth about man” as Pascal, Charles Péguy, and Pope John Paul II all put it in slightly different ways. There is a great deal of verisimilitude in the religious account of “fallen” human beings still imbued with free will and moral conscience. Not all reason is “autonomous reason.”

I remain most indebted to the Strauss who upended modern reductionism and recovered the dignity of the Lebenswelt, the common world where good and evil, the noble and base, and reasonable moral and political judgment, first come to sight. The “cave” image from Plato’s Republic has its manifold uses reminding us of the dignity of the “examined life.” But the philosopher’s dialectical “clarification” of common opinion and the common world of moral-political human beings can never finally leave “common sense” behind, if philosophy is to do its salutary work. Complete “liberation” from the life-world culminates not in philosophical wisdom, but in a kind of refined nihilism, one that is more estranged from the truth than old-fashioned “common sense.” Gregory Bruce Smith has argued this point quite compellingly in his 2018 book, Political Philosophy and the Republican Future: Reconsidering Cicero. In the end, classical political philosophy remains “phenomenological” in decisive respects, or it risks being nothing at all. Theory must learn from practice, and not just the other way around. In this sense, the relationship between theory and practice can never be simply hierarchical.

Let me end with a capital point inspired by Roger Scruton and his intellectual biographer Mark Dooley. As Dooley shows in his new edition of Roger Scruton: The Philosopher on Dover Beach, Scruton came to believe, rightly in my view, that in the late modern world, philosophy is obliged in important respects to become “the seamstress of the Lebenswelt.” Being “citizens of a small and intimate city-state,” Plato and Socrates could presuppose “publicly accepted standards of virtue and taste” largely formed by a “single collection of incomparable poetry.” We, in contrast, live in a decaying late modern world “ravaged by the culture of repudiation and disenchantment,” one that is bereft of “the certainties once provided by our common culture.” As Scruton puts it, philosophy “has been deprived of its traditional starting point in the faith of a stable community.” Socratic interrogation, as Eric Voegelin called it, remains central to the life of intellectual inquiry, and fundamentalism—religious and secular—remains deeply suspicious of it. But Socratic skepticism today must affirm as much as it questions, and it is obliged to question (and repudiate) facile relativism and the kind of skepticism that leaves the search for Truth behind. If philosophy does not vigorously defend the truths inherent in common life, it risks foreswearing its ancient and venerable “promise” to help us “to live well and wisely.”

Not all Straussians will agree with this “correction” of Socratic philosophizing occasioned by the threat of our suffocating culture of repudiation and negation, especially those committed to a more Epicurean, and anti-political, account of the philosophical life. But I’m inclined to think Strauss would precisely because he was no Epicurean and had a profound sense of moral and political responsibility.