As with the English Civil War, our own divides will not be resolved intellectually but through politics.

A Great (Conservative) Disappointment

In 2000, the Weekly Standard’s Fred Barnes published an article in which he argued California’s influence was waning. As it became more Democratic and more progressive, Barnes said, the state’s quality of life had declined and its influence on the nation as a whole had been blunted. I happened to have lunch with a conservative journalist about the time Barnes’ article came out, and I asked whether he thought Barnes’ analysis was right or wishful thinking. He smirked slightly and said, “Wishful thinking.”

What my friend meant by “wishful thinking” is that California, the erstwhile Land of Reagan, had by then become a deep disappointment to conservatives who remembered its dynamism as the nation’s leading Sunbelt state in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s but, contra Barnes, hadn’t lost its power to influence. As Michael Barone lays out in “Paradise Lost,” during the mid-century period, the state was governed by an optimistic, and, frankly, activist post-war consensus built on a broad agreement between Republicans and Democrats about what was needed to build California’s future. And it worked: California became a modern, dynamic, and gob-smackingly prosperous state that was not just synonymous with, but was the archetype of, the American dream projected onto the big screen for the whole world to see. Barone masterfully reconstructs this history, pointing out how Republicans and Democrats, while never relenting in their partisanship, shared an agenda to build the highways, water infrastructure, universities, and public schools necessary to create the virtuous cycle of ever greater wealth and opportunity.

One of the questions raised by Barone’s analysis of contemporary California is whether this pace of growth and dynamism was ever going to be, or could be, a permanent feature. The “mid-century moment” in which California played the leading role was the product of an extraordinary alignment of international and national factors resulting from America’s post-war global dominance. The vast publicly-funded infrastructure that was both cause and effect of the state’s explosive growth had to be maintained, a task that grew more challenging as the height of the post-war boom faded. In the words of the late Herb Stein, “if something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” California’s growth didn’t stop but its early growth subsided to more normal levels—about 3.5 percent per year on average—as a mature, heavily populated state.

To use a California-ism, this reversion to something closer to the mean has been a huge bummer in multiple dimensions. While the state’s economy has grown faster than the nation as a whole since the late-1970s, it is far from the peak of the century-long boom Californians had come to expect as a birthright. A smaller pie—or at least one that hasn’t gotten bigger as fast as it had in the past—constrains choices and has moved the state from a sky’s-the-limit hopefulness to an increasingly fierce competition for resources—fiscal and natural—that no longer feel as abundant as they once did. In terms of government rent-seeking, Sacramento feels a lot like Washington, D.C.—only without the unlimited borrowing power of the federal government that permits the indefinite postponement of tough decisions through deficit financing.

Tepid growth and competition for resources have contributed to another, even less wholesome trend in California: ethno-political scapegoating, a topic Barone treats lightly but which has operated in tandem with a dramatic shrinkage and weakening of the Republican party.

In 1994, then-Governor Pete Wilson, seeking re-election, tied his fortunes to Proposition 187, an amendment to the state constitution prohibiting undocumented immigrants from accessing most public programs including education and health care. The initiative’s proponents argued the presence of illegal immigrants in the state had caused economic hardship and worsened the state’s crime problems. By excluding the undocumented from public services, the argument went, the state was conserving public resources for citizens and otherwise demagnetizing California as a destination for dangerous and violent illegal immigrants. Prop 187 passed by a wide margin and was interpreted as a vindication of Wilson’s political strategy of “juicing” the conservative white vote through racialized appeals. Subsequent constitutional amendments banning affirmative action and limiting bilingual education were also successful. While all three amendments enjoyed substantial support from minorities they were interpreted, ex post facto, as political assaults on nonwhites.

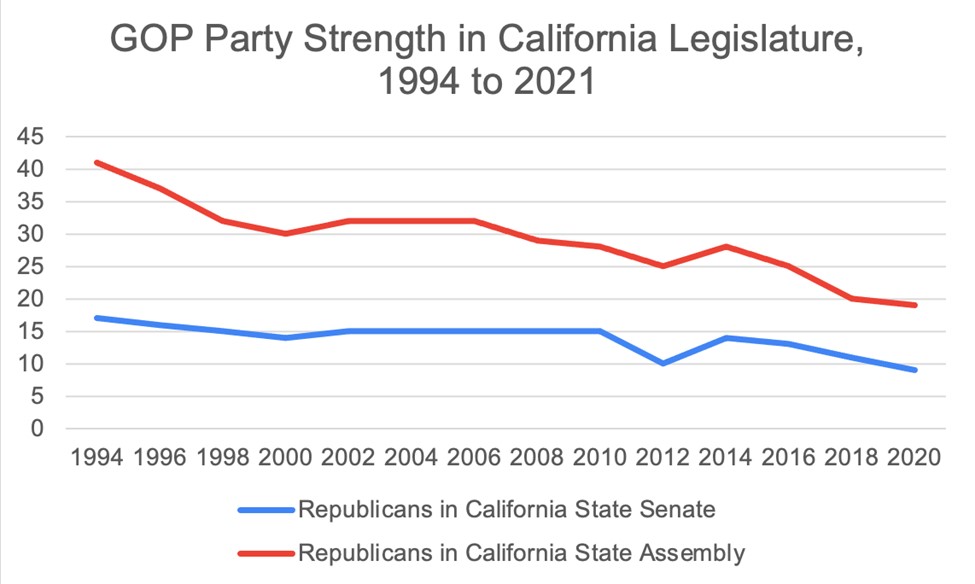

This reinterpretation of the social and political meaning of Prop 187 and its progeny correlates to a precipitous decline in the Republican Party’s competitiveness at the state level. Here’s what party control over the state government has looked like since 1994:

The collapse of the GOP in the state legislature was even more pronounced than the chart suggests. Following the 1994 election that saw Prop 187 pass and Wilson returned to office, the Republicans gained a tenuous and temporary hold over the California State Assembly notable for the extraordinary maneuvering of then-Speaker Willie Brown who, by various forms of political wizardry, managed to hold onto the speakership. Since then, it’s been a more or less continuous downwards trajectory for the GOP with its Assembly numbers dropping from 41 in 1994 to just 19 today. In the State Senate, a 21 to 17 Democratic majority in 1994 has become a 31 to 9 (you read that last number correctly) Democratic majority today.

The most obvious factor in this transformation is a hardening of Democratic support among Hispanics and other minorities whose communities seem to have had second thoughts about the racially-tinged propositions they earlier supported. But a significant contributor has also been a shift in white voting allegiances from the GOP to the Democrats. It isn’t just that conservatives have migrated away from California. The increasingly purple-to-blue tints of states like Nevada, Arizona, and Colorado (not to mention cities like Salt Lake City and Boise) suggests that while California migrants may skew conservative within the state, outside of it, they tend to be viewed as more liberal. The ones that stay behind skew even more liberal—the end result being an overpowering Democratic coalition facing off against a rump conservative faction unable to appeal broadly to suburban voters. The 50 percent decline in GOP legislative voting power since 1994 has rendered California a one-party state with no effective check on the (mainly) Democratic governors and legislatures that have run the Golden State—into the ground, conservatives say—over the past two decades.

If the GOP doesn’t find its way back to a coherent brand and agenda that educated and pragmatic suburban voters can support and non-white voters don’t recoil from, the national GOP could suffer the fate of the California GOP.

This story should sound familiar to national Republicans. Donald Trump’s 2016 victory had a number of sources, among them a weak Democratic nominee who ran as if she was being elected by plebiscite rather than the Electoral College and misgivings about trade and other economic policies that voters came to believe had hurt Rust Belt cities and towns in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. In parallel, however, was Trump’s uber-Wilsonian (Pete, not Woodrow) appeal to the politics of race, fear of immigrants, and his stoking of white voter grievance turning out millions of low-propensity voters in just the right places.

This heightening of racial, social, and economic tensions continued during Trump’s term in office and the political effects look similar to what happened in California: no great damage to the party’s standing among minorities—Trump did better among Hispanics in 2020 than he did in 2016—but a substantial fall-off in support among whites living in America’s suburbs repelled by Trump’s confrontational style and appeals to race-based politics, and, in 2020, by his mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic. These defections came to matter a great deal in the 2018 mid-term elections, costing the Republicans the House, and the 2020 general election with Trump not just losing re-election but the Senate as well in Georgia’s dual run-off elections. As has been noted, it was a near-record turnout among minorities in Atlanta combined with shrinking Republican margins in the Atlanta suburbs that made the difference in turning Georgia blue in the general election and the Senate races.

Perhaps 2020 was a one-off. President Biden’s economic agenda might ignite an inflationary spiral or his foreign policy result in another unpopular war thereby creating an opening for the GOP to regain power. Something analogous to this happened during Gray Davis’ truncated tenure as California governor when a budget crisis, combined with the collapse of the state’s electrical grid, brought into office the Terminator himself, Arnold Schwarzenegger, to restore order. Even if Schwarzenegger’s governorship was a coda, it still suggests that events can occasionally drive counter-cyclical political outcomes.

If events do not conspire against Democrats, however, it’s at least conceivable the nation might follow California’s political trajectory. Despite the 2018 and 2020 losses, the GOP has reinvested in Trump, the traumatizing memory of the January 6 riots more than offset by the fear of Trumpier-than-thou primary election challenges. As George Will said recently, “The Republican Party today lives in terror of its voters, and that’s, again, a very dangerous political condition.” If the GOP doesn’t find its way back to a coherent brand and agenda that educated and pragmatic suburban voters can support and non-white voters don’t recoil from, the national GOP could suffer the fate of the California GOP. Regardless of one’s political perspective, such a lock-out would be dangerous development for a system that requires vigorous partisan competition to maintain balance and accountability. One needs to look no further than California itself for confirmation of that.

The error, if there is one, in Barone’s (and before him Barnes’) analysis of California is in believing that because the state is no longer a model for the nation it is, therefore, not a trend-setter. A state with 40 million people producing 14.8 percent of the national GDP (compared to 9.2 percent for Texas and 5.1 percent for Florida), speckled with prestigious universities, and home to globally-dominant entertainment, media, and high-tech industries cannot help but set cultural, social, and political trends. But that doesn’t mean those trends will be positive or even what conservatives would prefer.

In the early days of the Obama administration as Democrats were pushing through a then-massive $787 billion stimulus package and preparing for a partial federal takeover of health care, someone asked me if I thought the U.S. was becoming France. “No,” I said, “but I am worried we may become California.” And I still am.