Fracture or Fusion?

Those who have paid attention in recent years to the inner workings of the American right may have noticed some shifts in the way many conservatives explain their beliefs. Among these: A reclamation of the mantle of nationalism; increased trust in the state, even the federal government, and a corresponding comfort with using the levers of power for conservative ends; and a renewed assertion that government is instituted among men primarily to advance the common good.

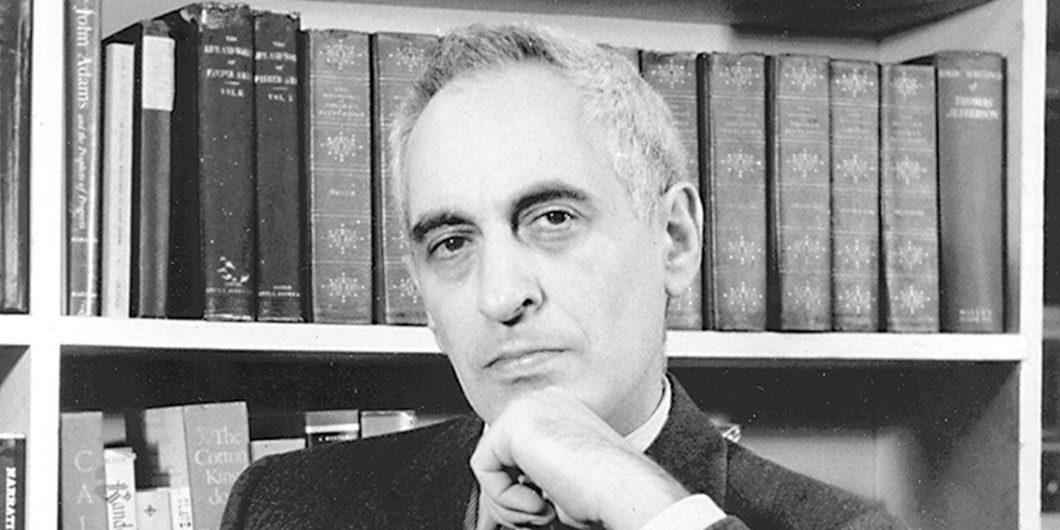

These New Conservatives—more communitarian and socially conservative in disposition—have adopted a noble intellectual tradition that has competed with “movement” conservatism for decades. Many of the criticisms that animate New Conservatives’ separation from movement conservatism had been largely dormant until the rise of nationalist-populist sentiment that accompanied the ascent of Donald Trump. But they were once the subject of intense debate during the era of conservatism’s political ascent, especially embodied in the arguments between Frank S. Meyer of National Review and Russell Kirk of Modern Age.

These debates are relevant once more as today’s New Conservatism faces a pivotal choice. After four years of tasting power on a national scale, New Conservatives are relegated to opposition for the first time since their revival. They may now choose between fracture and fusion: Should New Conservatives continue to stand apart from libertarian-conservatives, advocating for robust government power to affect the common good? Or should they instead gird themselves for at least four years of defense by backing off their communitarian rhetoric and banding together with right-liberals and free-market fundamentalists?

A review of Meyer’s critiques of Kirk points to the enduring preferability of fusion, especially as conservatives find themselves once again on the political periphery. Though New Conservatives might dismiss Meyer’s prognoses as mere libertarian apologetics, they would do well to remember what it was like being a conservative in the wilderness—standing athwart a hostile culture and national government—and draw on the wisdom of prior generations.

Collectivism Rebaptized

Many books can and have been written on the Meyer-Kirk debates, which have essentially been cast as a dialectic between reason and tradition, between freedom and virtue. At risk of oversimplifying (“it is not an easy matter to pin down Dr. Kirk’s thinking,” Meyer wrote), Kirk’s first political principle was prescriptivism: A community should use its own traditions, rather than its pure reason, to guide its political decision-making. Moreover, Kirk held that the American tradition was an overwhelmingly communitarian one that built on Christian ethics to establish virtuous communities. His concern with Meyer’s emphasis on liberty was that it would soon descend into “license,” as individuals unmoored from obligation and traditional sources of virtue would use their freedom to act in ways that would destabilize the American way of life.

Meyer saw that such a philosophy lacked the kind of neutral principle necessary to reject progressive collectivism, because it relied on its Christian substance to justify subordinating the individual. He branded Kirkianism “collectivism rebaptized” in a 1955 essay bearing that name, pointing out the contradiction between Kirk’s social criticism, which is “full of just and shrewd critiques of aspect after aspect of the contemporary world,” and his “condemnation of the ideas and the institutional frameworks which are essential to the reversal of the trend” towards the collectivism that gave rise to it.

For conservatives in a progressive culture, an agenda of codifying communal tradition is a recipe for disaster, because it fails to codify its intended tradition. “Despite the evidence of their senses,” Meyer writes, New Conservatives “brush away the prevailing power of the outlook which is in fact dominant in the schools and universities, dominant in the mass-communications industries, dominant in the bureaucracy of government, dominant in every decisive position in the land.” Insufficient appreciation for the importance of freedom among political minorities is endemic to a system of thought focused on identifying and ordering society towards a particularistic idea of virtue contained within its traditions, because communal traditions are inherently majoritarian.

Meyer insisted that the individual’s innate dignity is conservatism’s “first principle” and that it demands vigorous limitations on state power in politics and economics.

In a heterogeneous country like ours, many divergent views exist of what tradition comprises. Meyer shared Kirk’s substantive vision of American traditional norms but observed in the 1960s that the conservative tradition was losing. Progressive officeholders understood their election as a mandate to entrench progressive values, arguing that those were the American traditions worth elevating. Conservative majoritarians thus faced some severe problems: How could they purport to represent the will of the people while not in power? What recourse does a conservative have when progressives claim to speak for the members of their political community?

The best recourse, one Meyer deduces on Kirk’s behalf from Kirk’s examination of “ultimate values” found in “the accumulated wisdom of Western civilization,” is “a belief in the unique value of every individual person.” By insisting on every individual’s inherent dignity, the conservative can build a coalition against the encroachment of the public on private integrity. Meyer castigated Kirk for dismissing individualism as the philosophy of “defecated intellectuals.” Indeed, Meyer argued, only robust individualism provides the intellectual and institutional framework for resisting progressive collectivism by asserting the primacy of the individual and his God-given dignity over the totalizing state.

What about Kirk’s “voluntary community,” the civil society institutions that stand between the individual and the state? Without denying the importance of such institutions, Meyer forced New Conservatives to state their ends: “All social institutions derive their value and, in fact, their very being from individuals and are justified only to the extent that they serve the needs of individuals.” All conservatives share the goal of human flourishing, which ultimately depends on how institutions such as families and churches advance the welfare of individuals within and around them. The same goes for the state: Even if it exists primarily to advance the common good, its success is measured by the extent to which its citizens benefit. Meyer thus insisted that the individual’s innate dignity is conservatism’s “first principle” and that it demands vigorous limitations on state power in politics and economics.

Meyer’s individualism invites the problem of unconstrained citizens potentially destabilizing the very state that protects their freedoms. While not disputing that there existed an objective moral order that ought to govern an individual’s behaviors, Meyer—perhaps motivated in part by his own status as a Jew—criticized Christian communitarianism for being unable to “distinguish between the authoritarianism with which men and institutions suppress the freedom of men and the authority of God and truth.” Free to pursue virtue, citizens should look to tradition and religion for guidance—but the state should stay out of it.

This defense of pluralism should sound familiar to anyone well-versed in the theories of religious freedom propounded by America’s founders: Truth and the pursuit of virtue are matters between man and God. When others meddle in this sacred space, they succumb to the “totalitarian temptation,” bringing the private life of all into the realm of the public, trying to redeem violative means with the baptismal water of righteous ends. Fighting this temptation is crucial to conserving the pluralistic American tradition.

New Conservatives necessarily endorsed some degree of coercion to nudge citizens towards the highest good. But coercion can only be applied effectively by a majority in the name of a communally accepted “common good.” This does not bode well for conservatives, especially those of a traditionalist bent who find themselves in an increasingly defensive posture.

The Individualist Reflex

Today, New Conservatives preach communitarian traditionalism but understand reflexively that they are losing the fight to define the common good. When the dominant culture acts on its own understanding of the common good to nudge conservatives, even Kirk’s intellectual heirs inadvertently admit Meyer’s victory by defending themselves with the language of fundamental individual freedoms.

Consider the recent case of Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO), among the most vocal critics of the supposed libertarian “dead consensus” dominating Washington. After Hawley’s support for President Trump’s failed bid to overturn the election, Simon & Schuster announced it would not publish Sen. Hawley’s upcoming book. His statement in response is instructive: “Let me be clear,” he wrote. “This is . . . a direct assault on the First Amendment. Only approved speech can now be published. This is the Left looking to cancel everyone they don’t approve of. I will fight this cancel culture with everything I have.”

Rededication to our Constitution comprehends a defense of both freedom and virtue, allowing more communities to determine their norms for themselves, while guaranteeing the rights of all to pursue virtue as they see fit.

Legal and constitutional analysis aside, Hawley’s explanation of Simon & Schuster’s wrongness fails on common-good grounds. Surely a common-good regime would have the power to deem destabilizing speech seditious and ban it. Surely it would celebrate corporate actions to deplatform those who would undermine the republic. A culture assured of its orientation towards the highest good would doubtless be a “cancel culture” in practice, heaping social opprobrium—if not the hand of the state—on those who subvert it.

But the senator defaults to an individualist argument: Every person has the right to speak freely even if he contravenes “approved” dogmas. This remains true even if the effect of such speech is deemed contrary to the common good, because we trust no one to have so firm a grasp on what the public good is. Hawley may not admit in the abstract that individual freedom is a political end in itself, but his revealed preference speaks volumes.

Ironically, Hawley’s best appeal to the common good is that government should coerce Simon & Schuster into publishing whatever the state chooses. This would empower the state with enormous coercive force lacking a limiting principle within the common-good framework, and could just as easily apply to, say, Hawley’s church. Under a common-good state regime, civil society—the cornerstone of Kirk’s vision—would fare no better than the individual. Religious traditionalists could hardly choose a worse path.

Rather than pursuing particularistic and minoritarian visions of the common good, conservatives should embrace Meyer’s “first principle” of liberty that stems from traditional notions of individuals’—and communities’—inviolable dignity. Building a viable opposition that can attract numerous dissident factions requires appealing to dissidents’ shared interests, which revolve around such a neutral principle. Standing apart from champions of liberty is a gift to those most hostile to traditional communities. In Meyer’s words, New Conservatives’ “virulent rejection of individualism and a free economy threaten no danger to the pillars of the [collectivist] temple.”

At the same time, individualists should take some New Conservative critiques seriously. The argument that individualists trust too much in market forces to stand in for what is good should temper the impulse to say that all choices are correct choices. Upholding a stable republic of free citizens is a challenge bordering on a paradox; conservative reverence for tradition, especially religious tradition, makes a necessary counterweight against freedom’s tendency to descend into licentiousness. But that does not mean that a particular conception of virtue should take shape in the realm of law and coercion rather than norm and education. If that isn’t clear now, perhaps four years of progressive control of the federal government—and nearly every other commanding height of our national culture—will make it so.

Lessons for Conservatives in Exile

Especially in times of opposition to prevailing political fashions, Meyer offers conservatives an opportunity to realize their common interests and principles. Simultaneously defending liberty and traditional communities while in political exile should not present such a challenge.

The first source of commonality is, unsurprisingly, a common enemy. “The desecration of the image of man” effected by the progressive project, “the attack alike upon his freedom and his transcendent dignity, provide common cause in the immediate struggle.” Perhaps this best explains Sen. Hawley’s reflex. Denying a man his fundamental freedoms is an affront to his dignity, tantamount to denying that sacred principle that man is created in God’s image. Part of the miracle of the American tradition is that it instantiates in law protections of such dignity. These protections manifest as freedoms. That no man is fit to lord over his fellow citizen is the fundamental first principle of American equality. Ours is a tradition of liberty; libertarians and the traditionalists share significant ground when faced with opponents who would desecrate it.

Opposition is not all that binds the right. “The development of a common conservative doctrine,” Meyer writes in “Freedom, Tradition, Conservatism,” occurs when both factions “recognize not only that they have a common enemy but also that, despite all differences, they hold a common heritage.” Meyer thus encourages all Americans dissenting from the progressive project to embrace constitutionalism as the beginning of political wisdom. “Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, Hamilton, Adams, Jay, Mason, Madison—among them there existed immense difference on the claims of the individual person and the claims of order, on the relation of virtue to freedom.” Our tradition, inherited from those great men, is “based upon the understanding that, while truth and virtue are metaphysical and moral ends, the freedom to seek them is the political condition of those ends—and that a social structure which keeps power divided is the indispensable means to this political end.” Rededication to our Constitution comprehends a defense of both freedom and virtue, allowing more communities to determine their norms for themselves, while guaranteeing the rights of all to pursue virtue as they see fit.

The American creed already has its lodestar. By aligning in its defense, the right can prove a powerful force against the passions of the day.