Can UATX reclaim what used to be the heart of historical study: political, institutional, military, and diplomatic history?

Harvard Debates Itself

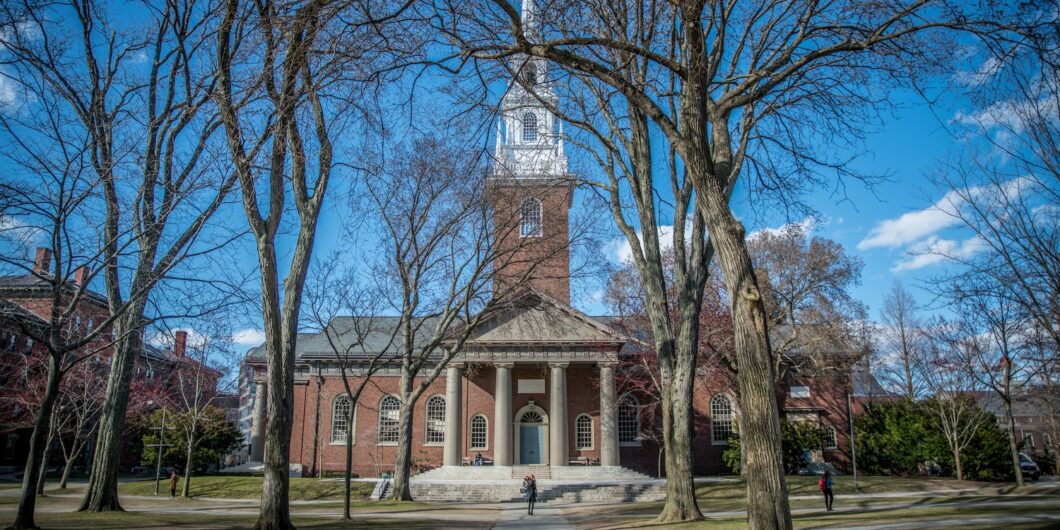

Harvard, which FIRE recently ranked near the bottom for academic freedom among leading US universities, took a few baby steps this week to re-establish a semblance of open debate. Unsurprisingly, the initiative came from the undergraduates, not the faculty, let alone the administration. The occasion was the first debate sponsored by the newly-formed Harvard Union Society. One of the debaters was pained to admit that the student champions of free debate seemed to be conservatives, not fellow liberals. Judging by the number of male students wearing jackets and white shirts instead of the usual student slobwear, this must have been true. The issue was meritocracy, and the resolution to be debated was: “Should Harvard admissions be more meritocratic?” In the background, of course, was the Supreme Court’s recent spanking of Harvard for its admissions practices in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard. There was a fine turnout for the debate, standing room only in a room that holds a hundred people.

Unlike Oxford and some other British universities, Harvard has no tradition of public debate, and it showed. The organizers had no idea of how to formulate a provocative resolution, and the debaters struggled to find areas of disagreement. Gingerly, over the years, both have been approaching the political center from their comfort zones on the left. Steven Pinker, the famous cognitive psychologist, is a leader in Harvard’s new Council on Academic Freedom, now 150 members strong. Good for him. Michael Sandel, arguably the nation’s premier political philosopher, is not a member, but professed his support for public debate on controversial issues. Around Harvard, where it is common to shout down or disinvite speakers you disagree with, that counts as courageous.

If the audience expected the debaters to strike out onto the open seas of academic freedom, however, it was disappointed. There was not a great deal of daylight between the two professors about the subject of meritocracy. There was some illumination, but no sparks flew. Both professors agreed that Harvard should not admit legacies by preference. Both seemed to regret that racial preferences had been judged unconstitutional, though neither admitted that those preferences had of necessity excluded more qualified Asian applicants. Both agreed that it was desirable to have more students from disadvantaged backgrounds on campus and deplored the disproportionate presence of upper-class children. Both agreed that SAT tests and grades were the best existing measures of merit, though they disagreed slightly about the weight to be assigned to each. Both were sorry that Harvard produced so many fund managers, consultants, and others whose goal was to make money upon graduation. (These miscreants, it seems, have now replaced investment bankers and corporate lawyers in the professorial bestiary.) Both thought Harvard should be producing more civic leaders trained in moral reasoning and scientists who would put a stop to climate change. Both agreed that the lucky students who had been admitted should show up for class more often.

The disagreements were mild. Professor Pinker thought the criterion for admission should be the ability to make best use of Harvard’s extraordinary resources: museums, libraries, rare manuscripts, laboratories, and the teaching of brilliant scientists and scholars. Professor Sandel preferred admitting those with a serious commitment to serving the community. He opined that the admissions office should think more about the common good. Professor Pinker thought Harvard students should be smarter, which meant weighting SATs more. Professor Sandel thought that extracurriculars should receive greater consideration, and that it wasn’t worth sacrificing egalitarian goals for higher average SAT scores. Harvard students were already smart enough (applause). He didn’t explain how admitting more disadvantaged students could add to the richness of undergraduate experience he so valued. There hovered on the edge of consciousness, without quite coming into the open, the realization that advantaged students did have some advantages, after all, when it came to joining in those scintillating Harvard conversations. They had traveled more, been to more concerts and museums, started more start-ups, and met more interesting people at their parents’ houses and country clubs.

The debate, like most things at Harvard, had a self-congratulatory tone. The self-obsessed state of mind at Harvard is something I noticed right away when I came from Columbia to join the faculty here 38 years ago. (In Harvard parlance, by the way, the word “here” always means “at Harvard,” even if the conversation takes place in Tokyo.) At Columbia, nobody talked about “being at Columbia” as though that condition implied membership in a global peerage. No student talked about the effect of “dropping the H-bomb,” that proud-awkward moment when—admitting to an acquaintance that you went to Harvard—your secret identity as Captain Supersmart was revealed. At Columbia, when I was a grad student there, we talked mostly about art, music, history, and old books. We liked to describe ourselves as “living in New York and going to school,” location undisclosed.

Maybe it’s my lack of a crimson pedigree, or maybe it was my exposure to real debate in the Oxford Union, but I found myself dissatisfied with the Harvard event. Despite Harvard’s pontifical proclivities, I found the whole discussion a bit parochial. I couldn’t help noticing its historical shallowness, its lack of self-criticism, and its failure to make fundamental distinctions and clear definitions.

The debate, like most things at Harvard, had a self-congratulatory tone.

For example, what, exactly, is a legacy, and why are they so undesirable? Is a legacy the child of any Harvard graduate, or only the wealthy ones? Or do you have to be the scion of several generations of Harvard graduates—Harvard blueblood, in other words? Does it include the children of our black and Hispanic graduates, who are rather numerous and often wealthy? Moreover, and contrary to popular opinion, it is not the case that all Harvard graduates become rich and famous. Some become schoolteachers or cellists or aid workers in foreign countries, surviving on a pittance. Should their children be branded with the infamous label of legacy? If the children of all Harvard graduates are legacies, it’s absurd to disadvantage them in the admissions process, surely. Even if you define legacy as a “wealthy graduate,” the question arises: just how wealthy? And does the university really want to alienate families that have served it for generations and maintain its traditions? Won’t that weaken the institution, as I’ve argued elsewhere? Isn’t it the case that one reason why people want to get into Harvard is to meet fellow students from old and wealthy families who might be able to help them get on in life? If the goal of our admissions policies is to help disadvantaged students enter the ruling class, isn’t the presence of legacy students an important means to that end?

Another distinction I missed (standard in the literature) is that between socio-economic meritocracy and political meritocracy. Political meritocracy is easily defended: everybody prefers to be governed by able persons of proven competence, and a good political system will be designed to attract and promote such people. Harvard certainly contributes more than its share to the governing elite: just look at the federal bench and the Supreme Court. Ten percent of all members of Congress are Harvard graduates. As evidenced by this week’s debates, however, many Harvardians think the goal of our admissions office should rather be to select the rising socio-economic elite, to choose winners and losers for the country as a whole, to regulate who should have access to the best jobs and the highest incomes. In the absence of a beneficent deity, it must step in and ensure fairness in American society. Missing from the debate was any humility about whether the university admissions office was entitled to play such a role, or any modesty about what the university’s actual purpose was, i.e., education. Maybe what we professors should be debating is how best to educate scientists and scholars rather than how to engineer society to make it fit our ideas of equity.

Also standard in the literature on meritocracy is a distinction between merit and desert. Successful meritocracies are initially chosen on the basis of merit (defined as ability or potential, the kind of thing tested on exams), but people deserve success or promotion when they have proven effective in their jobs. For example, in the meritocratic system of the imperial Chinese bureaucracy, which goes back to the seventh century, entry into imperial service was secured through a qualifying examination, but promotion up through the fifteen ranks of mandarins was (in principle) a result of successful job performance. From the point of view of meritocratic theory, it might be argued that Harvard’s power to determine winners and losers via admissions acts to prevent deserving people from achieving success. University social networks are the natural enemy of desert, similar in this respect to the old-boy system. They are influence rackets designed to advantage your friends over strangers who may have better qualifications. It’s no accident (as the old Marxists used to say) that online social networks were invented at Harvard. If (Heaven forfend) I were a Marxist, I might even conclude that all this talk about meritocracy is designed to conceal what Harvard is really about.

One of the respondents at the debate, a delightful young eccentric in the Oxford mold, complained that Harvard, having sadly abandoned its original motto Christo et ecclesiae (“For Christ and the Church”), was now guilty of false advertising in flaunting its more recent one, Veritas. The real problem with Harvard, he said, is that it didn’t admit students with the moral capacity to search for truth. He didn’t propose a more suitable motto for contemporary Harvard, but (thinking about the Roman empire, as I always do) one occurred to me as I listened to the debate. It is the motto of the town of Arpino in Italy, the birthplace both of Cicero and the famous Roman general, Marius: Hinc ad imperium. From here to empire.