However hard we try to explain human behavior, there will always be some remainder that escapes us.

Science’s Assault on Free Will

What if peoples’ failures were never their fault but the product of genetic or environmental conditions into which they were born? Would such news be a cause for celebration regarding the newfound potential to improve these unfortunate circumstances and prevent human suffering, or would it be viewed as dangerous, a threat to the individual responsibility essential for any decent society? The question is not merely hypothetical but raised by the recent publication of a new book by Stanford neurobiologist Robert Sapolsky entitled, Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will. The culminating achievement of over four decades of research in primate behavior, Sapolsky is building upon his award-winning and best-selling work of 2017, Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. There he draws on a growing literature, which claims that human decisions are capable of strict causal explanation, insofar as they are the result of neurological stimuli entirely beyond our control. In recent decades, this emerging body of research has argued that the brain—not concepts such as the “will,” “reason,” or even “mind”—is the real origin of human action in the world, which itself is responding to myriad external causes.

Such scientific explanations of human behavior are thought to hold the promise of tremendous progress with respect to our notions of punishment and reward—in short, the meritocratic assumptions governing our moral, legal, and economic systems. For example, they have significance for how we treat practitioners of violent crime and other anti-social behavior. Scholars, such as Gregg Caruso, a philosopher at SUNY Corning who runs the Justice Without Retribution Network, point to such neuroscientific scholarship in his effort to bring about a more humane society which, he believes, will become possible once such crimes are seen as beyond free will. Rather than assigning blame and fulfilling a desire to punish “bad” people, such scientific naturalists prioritize the prevention of future harm by would-be offenders. Change the circumstances in which such people are raised and live their lives, the logic goes, and you create a more just society.

As Sapolsky recently told The Los Angeles Times, “The world is really screwed up and made much, much more unfair by the fact that we reward people and punish people for things they have no control over.” However, he argues, “We’ve got no free will. Stop attributing stuff to us that isn’t there.” The real victims, on this view, are those who could not act other than they did but were thrown into a world and unfortunate circumstances in which they could not choose and for which they were not responsible. That society punishes such people for their “crimes” merely compounds injustice on top of injustice. We are machines, not free agents, and it is believed to be incoherent to blame the firing of brain synapses for the problems they produce, rather than recognizing their origin in biochemistry—whether due to a life of poverty, childhood trauma, or simple genetic inheritance.

However, if there is no free will and all decisions are neurologically determined, how could we possibly “stop attributing” praise and blame to human conduct? In other words, the lack of freedom or agency that such scientists attribute to human behavior must be applied to themselves and those who become cognizant of their research no less than the human beings they analyze in society. For such scientists are, themselves, within society, not mere external observers of it. Having objectified the human beings of their research, behavioralists often lose sight of their own involvement and participation in the social world. The philosophical movement of the mid-twentieth century known as phenomenology has long identified this epistemological problem with scientific naturalism—it succumbs to a “self-forgetting” or “forgetfulness of being” of the scientific observer, whose own embeddedness within the social order is essentially neglected or forgotten. In the present case, this allows for the scientist to exempt himself from the problematic implications of a more thoroughgoing and consistent determinism.

The life of the free and responsible person, known only from within human consciousness, has every bit a claim to reality as the realm of human action, which alone is accessible to the external observer.

Additionally, it must be admitted that ascriptions of value such as “unfair” or “unjust” with regard to human affairs have no place in a world that is said to be devoid of free will. For concepts such as justice and injustice, right and wrong, are fundamentally dependent on the possibility of acting otherwise. To put this differently, once free will has been claimed by neuro-determinists to be impossible, the evaluation of our social institutions—e.g. a government’s criminal law system, a society’s distribution of wealth—no longer makes sense. Without the freedom to make different social or political choices, such institutions are simply what happens, unsusceptible to our moral approval or condemnation, since they were determined and thus beyond human responsibility. Our punishment of criminals for their “bad” behavior, itself, would have to be seen as determined (perhaps by a psychological need for retribution, etc). To claim that such policies and attitudes are “unfair” absent the ability to act differently is like criticizing a rock for falling downward as a result of gravity.

Further difficulties arise for the neuro-determinist when he considers the fact that he, himself, is involved in the paradoxical effort to persuade others of his position that there is no such thing as free will. For, there is clearly bound up in such arguments the assumption that those being reasoned with are free to change their minds based on the merits (or demerits) of the evidence presented. Good (or bad) scientific evidence is judged on its merits no less than the moral and political institutions that scientific naturalists, such as Sapolsky and Caruso, are persuading others to alter for their faults. Moreover, the rules of the scientific method themselves, quite unlike the rules of human behavior that the scientist seeks to discover, are prescriptive, and thus intended to guide inquiry that might be done well (or poorly) in the study of the natural or social world. This would appear to imply willful choices and the responsibility that is attendant to them, which accompanies the practice of science and according to which all scientists are held accountable. The decisions of the scientist and his peers are thus assumed to be free. Once again, such contradictions disappear or are obscured only when the scientific naturalist exempts himself (and those he attempts to persuade) from the determinism or lack of agency he would ascribe to all human beings.

If, however, one calls attention to this incompatibility between the perspective assumed by the scientific naturalist and that which he attributes to the human beings he studies—the views that are seen as external and internal to the “objects” of his investigation—one begins to expose the problems with this approach to human understanding. How, for example, would the human beings in society respond to the scientist’s claim that their consciousness and behavior are entirely predetermined? Such an encounter would bring information from the outside in, as it were, raising the conspicuous and problematic question of whether such an engagement should, on this account, be regarded as determined or free. Should the introduction of such information, then, be seen as part of a causal chain extending back to the scientist’s research, which was itself determined? Or should the individuals who “respond” to such information regarding their predetermined behavior somehow be seen as freer in light of this knowledge? The latter would, it seems, be the implication of the suggestion that in light of our awareness of our neurological determinism, we should “stop attributing” praise and blame within our moral, legal, and economic institutions. Such an admission would certainly raise new (and dizzying) problems for the neuro-determinist regarding whether such individuals have acquired agency and, seemingly, now deserve to be held accountable for their actions. Regardless, the point here is that such a question—no mere thought experiment, since we are in fact informed of such research—presses the scientific naturalist to acknowledge the sharing of a world between the scientist and the human beings he studies.

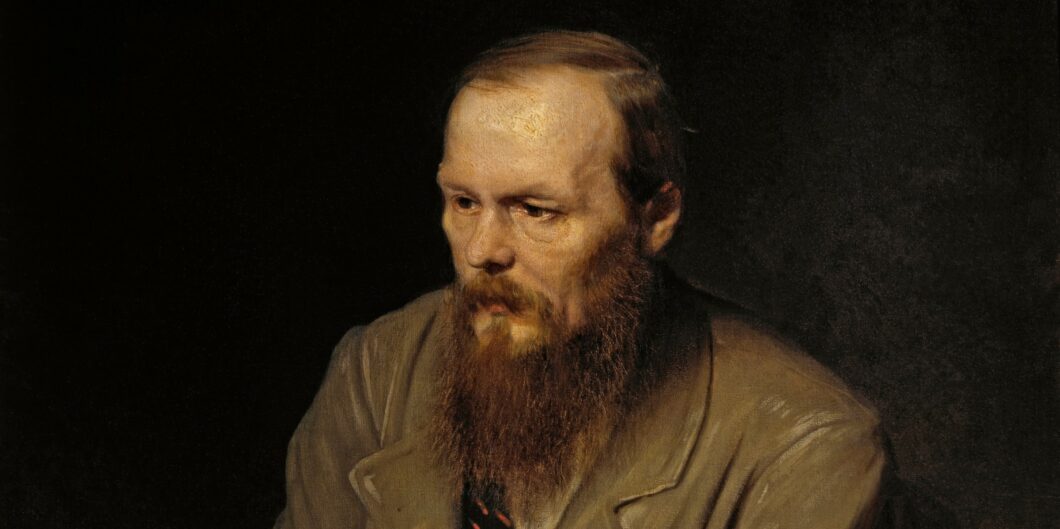

The perplexities that arise for a human being who is made “aware” of his predetermined behavior is perhaps first worked through in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s literary critique of scientism, Notes from the Underground. In this work, Dostoevsky’s Underground Man demonstrates the epistemological difficulties that result from such objectification of the human consciousness and the persistence of the individual’s experience of the free will. It is the arbitrary privileging of the external gaze of the scientific naturalist over the internal perspective of the human consciousness that inspires this tortured account of an individual trying to make sense of his objectification and the denial of a freedom that is experienced as real. This emphasis within Dostoevsky’s fiction on subjective consciousness and the real moral dilemmas confronted by the individual shows the centrality that choice and responsibility have to the author’s understanding of reality. Referring to the reputation he had received for being a “psychologist,” concerned with the inner workings of the conscience, Dostoevsky indicated that he preferred to think of himself as a “realist in the higher sense.” The experience of the struggles of conscience and the burdens of moral responsibility are, for Dostoevsky, a more realistic or authentic account of a human life than one which tries to explain everything in terms of what is observable and empirically verifiable from the outside.

The life of the free and responsible person, known only from within human consciousness, thus has every bit a claim to reality as the realm of human action, which alone is accessible to the external observer. The arbitrary privileging of the vantage point from without, which is attendant to the self-forgetting of the scientist, thus comes with a cost. It is the exclusion and neglect of the interior realm and the reality of a conscience and will that are irreducible to material causes. Confronted with a utopian socialism whose own objectification of the individual would turn him into an “organ stop” or “piano key,” the Underground Man thus stages his rebellion in the name of the life of the spirit. Dostoevsky affirms the status of this interior, spiritual realm alongside the laws of the physical universe when, in his inner monologue, he explains that it is not the results or satisfaction of preferences that give value to human choices but the very process of willing or striving itself. His famous statement that “two times two makes five” might be just as charming a thing as “two times two makes four” affirms what is valuable about the free will even in error. For in the will’s striving is earned the achievement of a self, whose being, because more than just a series of temporally fleeting, observable events, persists and acquires a character that transcends the flux of historical time.

Dostoevsky’s argument against scientism is a subtle one. He establishes the validity of the free will against scientific naturalism by drawing his readers into the internal experience of a fictional consciousness and its struggles with choice and responsibility, with whom the reader then identifies by virtue of their own past experience. Precisely because of the relatability of the internal experience of his fictional subject, we are able to see or comprehend the true ground of this interior reality: the universality of our spiritual struggle. Unlike the scientific naturalist who stands at a distance from the human beings he studies through their objectification, the reader of Dostoevsky’s fiction enters into a dynamic, interpretive engagement or dialogue with the subject, whose experiences are brought into relationship with the reader’s own. This relationship stands in contrast to the isolation of the Underground Man, which is clearly a function of his objectification and alienation experienced from above. Anticipating phenomenological critiques of scientism, Notes thus helps to overcome the self-forgetting that characterizes modern behavioralism—calling attention to the persons with whom relationships can be either developed or severed. And it is the remembrance of our own experiences of free will and responsibility, undeniable in their interior reality, which his literary encounter evokes.