One suspects true radicals wouldn’t seek out the university at all but cultivate a learning community outside of it.

Slavery with Benefits . . . Seriously?

The current fracas over the new Florida African American History standards is about how slavery is taught. The particular passage at issue concerns instruction about “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

Vice President Kamala Harris claims that in Florida “middle school students will be taught that enslaved people benefited from slavery.” In response, a member of the History Standards Workgroup and former Chairman of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, Dr. William B. Allen, says that the intent of this passage is “to show that some slaves developed highly specialized trades”—such as those of “blacksmiths, shoe makers, shipping and industry workers, tailors and teachers”—from which they, their families and descendants, and their society, benefited.

The “attempt to reduce slaves to just victims of oppression fails to recognize their strength, courage and resilience during a difficult time in American history.”

Are the new standards an attempt “to replace history with lies,” as Harris claims? Fact-checker Politifact says Harris’ statement is “mostly true.” Quite a number of politicians, news commentators, civic leaders, and concerned citizens have added their voices to the mix the last few days. Some have accused the Florida Governor and the Standards Workgroup of treating slavery as a “jobs program,” or as having a “net benefit” or a “silver lining.” One education advocate declared that crediting slaves with “resilience” is tantamount to accepting “White supremacy” and injustice, indoctrinating black youth with “a passive, vulnerable mindset that allows the system’s oppression to continue….”

Allen has responded by calling Harris’ accusation “categorically false.” The passage in question is part of the standards’ attention to “the vital contributions of African Americans to build and strengthen American society and celebrate the inspirational stories of African Americans who prospered, even in the most difficult circumstances.” Even in the midst of the oppressive system of slavery, Allen argues, there are instances of slaves demonstrating extraordinary pluck and resourcefulness, resisting the powerful tendency of slavery to make them into helpless victims.

So, where does the truth lie in this dispute? And why has it triggered such a national and rather nasty political firestorm?

To understand this controversy and do justice to what is involved and what is at stake, there are three questions that must be addressed:

- What does the passage in question mean?

- Is the passage true?

- Should the passage have been written differently, and if so, why and how?

- Are there long-term implications and perhaps deeper agendas driving this controversy?

The question of what the passage means is answered by basic grammar and logic. Unfortunately for Harris, her accusation doesn’t have a leg to stand on; it is a classic case of the “false cause” fallacy at work. This is a sleight of hand in which condition is substituted for cause. The Florida standards do not say that slavery caused slaves to benefit; the passage asks how, in some cases, those in the condition of slavery took it upon themselves to use their skills to advance themselves. Harris’s claim is also a non sequitur. If it were written as a syllogism, it would look something like this:

Major Premise: People often benefit personally from the skills they develop in their work

Minor Premise: Some slaves worked in trades requiring the development of specialized skills

Conclusion: Slaves benefited from slavery

Any schoolgirl can see that this conclusion violates the rules of logic. In fact, to my knowledge, no one involved in this debate has said or thinks that slavery was in any way beneficial to slaves. To accuse anyone of this is sheer malicious nonsense. The Veep and Politifact—and the myriad news sources, commentators, and civic leaders who have knowingly repeated such false, hurtful, and incendiary accusations – should know better.

The second and third questions are related and produce four possible answers:

A. Enslaved people didn’t develop any skills in any instance

B. Enslaved people developed skills but did not benefit personally from them in any instance

C. Enslaved people developed skills which, in some instances, they applied for their personal benefit

D. Enslaved people developed skills which, in some instances, they applied for their personal benefit, but we shouldn’t talk about this

A great body of scholarly literature exists demonstrating that some slaves developed not only specialized skills but, in some cases, became highly skilled workers. So A is clearly false. B is clearly false as well, based on ample scholarly evidence demonstrating the fact that a number of enslaved persons utilized their skills, both during slavery and after emancipation, to support themselves and their families. Indeed, some slaves bought their freedom with savings they accumulated from their work. Accordingly, C must be true. C is essentially a restatement of the passage at issue from the new Florida standards, albeit a bit stronger in that it requires proof of the benefit, not just that there was potential benefit in some cases. The statement by the Vice President, then, is patently false.

But was it wrong for the Florida Workgroup to make the statement, even if true? Or if not wrong, should they have worded it differently? Some people are offended by the presence of the word “benefit” in the same sentence as the word “slavery” because, even if the syntax and semantics do not bear it out, one might infer a causal connection between the two. Perhaps it would have helped to add to the sentence a phrase making clear the evils of slavery, modifying the passage to read: “how, despite the oppressive system of slavery, slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.” While this characterization of slavery as oppressive and inhumane permeates the Florida African American History standards generally, still, I am willing to grant that this added clarification, though unnecessary, may still have been valuable.

In sum, the passage of the Florida standards in question is actually about human determination, tenacity, and ingenuity in the face of the massive and awful obstacles imposed by the institution of slavery. Harris’s allegation is not only false and damaging, it diminishes the achievements of black Americans who, against the odds, labored so courageously to resist its effects.

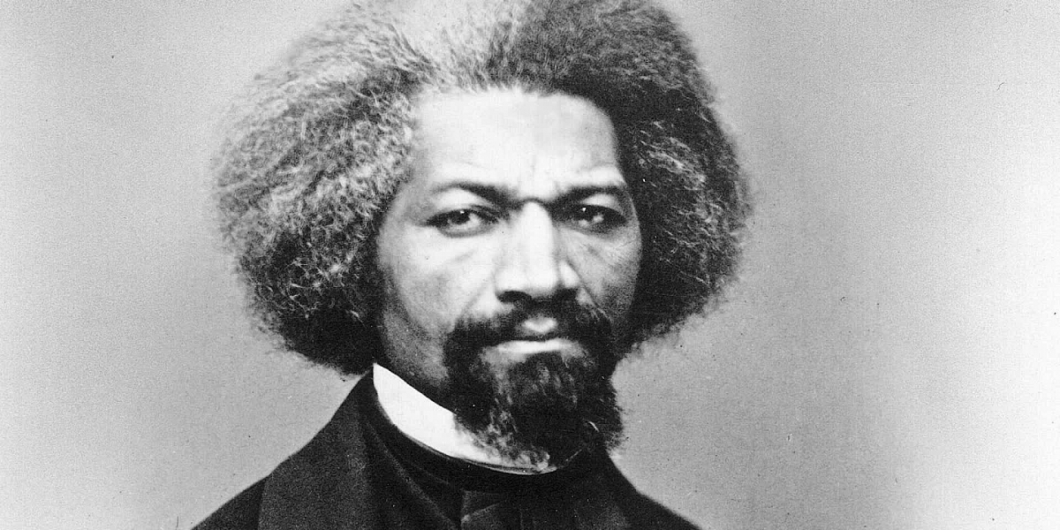

Whether real or politically fabricated, Harris’ sentiments are a continuum of the expression of racial distrust, anger, and resentment that followed in the wake of the George Floyd murder and which has since encompassed the nation. After this came racial protests that escalated into violence in Minneapolis and then Charlottesville. In cities across America, statues of Founders, generals, and other leading figures were slated for removal, vandalized, or torn down, including those depicting Thomas Jefferson, Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant, Francis Scott Key, and George Washington. Add to these Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Preceding all of these events was the introduction of the 1619 Project in the New York Times.

Since 2019-20 there has been a concerted push to tell the American story through the lens of the 1619 Project. Its instructional materials are in 4500 classrooms and at least five school districts have adopted its curriculum, including Chicago and D.C. Public Schools. “1619” is a narrative about the systemic racism, bigotry, and injustice that marks the nation’s founding and history. America was born in racism and is still today a racist, oppressive order, the only hope for which is a radical transformation of our existing policies and condition, not least of which are those informed by the principles of 1776. Clearly, more than racial equity is on the agenda of the leaders of this and other associated movements.

Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass not only helped to change the conditions of their fellow slaves, they helped to change the direction of the entire nation and the conditions of all its people.

The broader and long-term battle in America today is over the American way of life—what do we stand for? What are our most cherished principles? When Americans answer these questions they tend to divide into two groups, on the one side stand those who want to keep and revitalize the American tradition of equality and liberty, and on the other side are those who reject and want to replace that tradition with something they believe is qualitatively superior to it.

A few years ago Matthew Spaulding wrote a book titled, We Still Hold These Truths, invoking the Declaration of Independence and the place of its tenets in the American heart and mind. To fit the circumstances of the present day, that declarative statement might become interrogatory: Do We Still Hold These Truths? This is the central question of our time, situating the Declaration of Independence in the eye of the storm.

For progressive types who condemn slavery but reject the natural law basis of human equality as stated in the Declaration, the question that needs to be addressed is: what, then, is the moral basis for claiming that slavery is wrong? For Abraham Lincoln (just as later for Martin Luther King, Jr.) the assertion that slavery is wrong would have been baseless if deprived of its grounding in the idea of the natural equality of all human beings, as stated in the Declaration of Independence. As powerful as Lincoln’s attack on the institution of slavery was, however, even more powerful as counterargument were the living examples of men and women like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth.

Sojourner Truth escaped slavery with her young daughter in 1826. She was an abolitionist and active leader in the Underground Railroad, as well as an advocate for temperance and women’s rights.

After a number of failed attempts, at the age of twenty Frederick Douglass successfully broke his chains and escaped north to New York, where he declared himself a free man. In time Douglass gained national and international repute as an orator. Invited to speak on the Fourth of July in Rochester, New York, he chose instead to speak the next day, July fifth, asking, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?…What have I or those I represent to do with your national independence?” He continued:

Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? And am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits, and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?

Douglass himself ultimately answered his own question:

[T]he Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny; so, indeed, I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.

Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass helped to change not only the conditions of their fellow slaves, they helped to change the direction of the entire nation and the conditions of all its people. This is one of the “benefits” Professor William Allen is talking about—one of the “humble offerings” upon the altar of freedom, bestowed by Americans whose ancestors’ home had once been Africa, but who themselves belonged to the land called America just as that land belonged to them.

Certainly, these men and women are worthy of study in our schools, in Florida and across the nation. The question is whether our study of America’s past will enable us to live out and pay forward its “saving principles,” so as to contribute to healing our fragmented nation as they sought to heal an equally divided one, thereby making ourselves worthy of the benefits of their incommensurable sacrifices.