By stifling religion and the communities that form around it, the courts undermine religion's capacity to house safely our natural drive for meaning.

Supreme Failures from the Court

It should come as no surprise that many conservative legal thinkers consider Roe v. Wade to be among the worst decisions ever handed down by the Supreme Court. The fiftieth anniversary of Roe is also the first since it was overturned by Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. But many terrible decisions remain. The anniversary prompted us to ask: What are the worst of the worst?

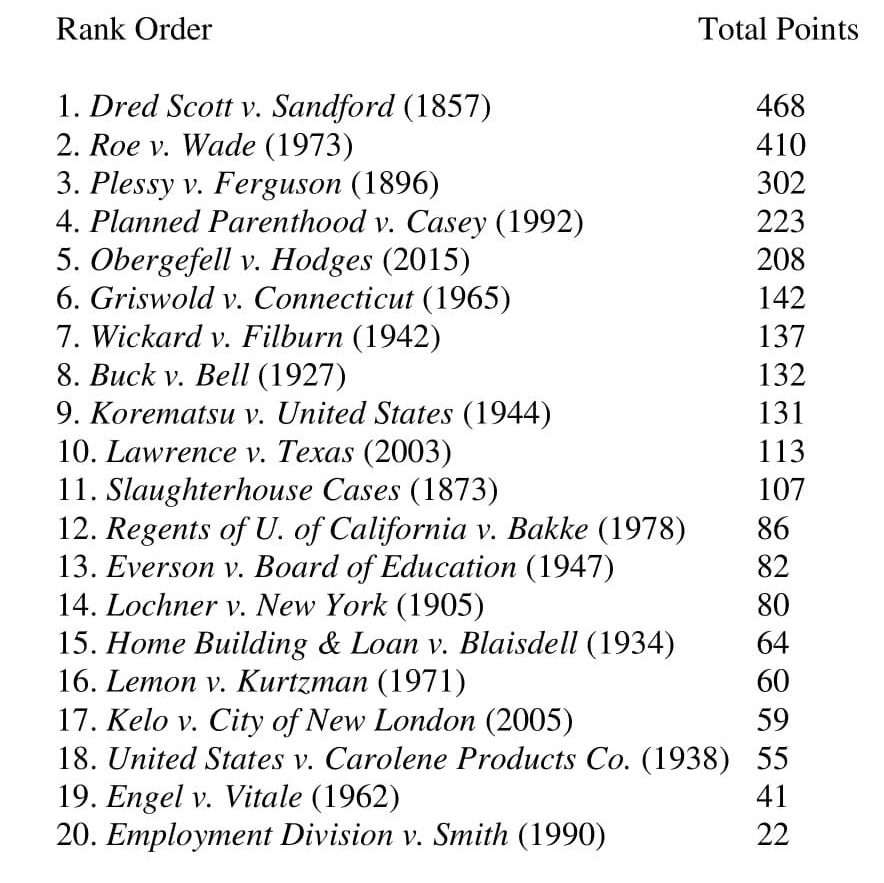

We decided to ask self-identified conservative and libertarian legal scholars to send us their own lists of what they considered to be the Court’s worst opinions. We then compiled a list of the twenty cases mentioned the most often and sent it back to scholars, asking them to rank the worst opinion, the second worst, etc. We gave every first-place vote ten points, every second-place vote nine points, and so forth. In all, we surveyed more than 100 leading conservative and libertarian legal scholars and received about fifty responses. There were some disagreements among the respondents, but there was strikingly widespread agreement about the very worst opinions.

Overall, our Dishonor Roll of opinions fell into four broad conceptual groups, the first of which included decisions that denied the full humanity of others. A second group represented the abuse of judicial power through the creation of nonexistent constitutional rights. Opinions in the third group failed to recognize or enforce limits on government power that actually are in the Constitution. And a final group consisted of opinions fundamentally misunderstanding the relationship of church and state and the contours of religious freedom. There is some overlap of opinions that could fit into more than one of these groups. Arguably all, or nearly all, could be said to fall into either the second or third—imposing what is not in the Constitution or failing to enforce what is. But we invited participants in the survey to comment, if they wished, on why they thought these were judicial blunders, and our groupings represent the reasons they gave.

Dred Scott is widely considered to have exacerbated the sectional conflict that Taney and the majority probably thought they were ameliorating, and to have hastened the onset of the Civil War.

Leading the first group was the worst disaster in the Court’s history: Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). The majority opinion, by Chief Justice Roger Taney, held that African-Americans “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.” In other words, African-Americans, whether enslaved or free, could never be citizens of the United States and their rights need not be respected as a matter of federal law. Moreover, Dred Scott held that Congress had no power to prohibit the spread of slavery into federal territories. As Abraham Lincoln recognized, the ruling jeopardized the nation’s commitment to its founding principles of equality and liberty and threatened even the people’s right to rule themselves. Dred Scott is widely considered to have exacerbated the sectional conflict that Taney and the majority probably thought they were ameliorating, and to have hastened the onset of the Civil War.

Fortunately, Dred Scott was overturned by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution (one of four Supreme Court decisions to be overturned in this way). These amendments did much to recognize the majestic principles, articulated in the Declaration of Independence, that all persons are “created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

Alas, the justices ignored this principle again when they decided what our scholars considered to be the second worst majority opinion ever handed down by the Supreme Court: Roe v. Wade (1973). In addition to conjuring a virtually unlimited right to abortion out of its own musings about “privacy,” the majority again determined, as in Dred Scott, that some citizens are not quite human and therefore unworthy of being protected as a matter of law. And, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992, number 4 on our list), the controlling “joint opinion” of Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter incomprehensibly conceded Roe’s lack of coherence as an exercise of constitutional reasoning, yet doubled down on the essential holding, shoring up the fatally flawed precedent with the bizarre statement: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” This inanity proved to have far-reaching implications over the next quarter century.

Dred Scott, Roe, and Casey stand for the proposition that some citizens do not need to be fully protected as a matter of law. According to our conservative and libertarian scholars, four additional cases reflect the kindred failure to honor the fundamental principle of equal human dignity:

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896, our number 3), permitting states to segregate and discriminate against African Americans;

Buck v. Bell (1927, number 8), upholding involuntary sterilization because “three generations of imbeciles are enough”;

Korematsu v. United States (1944, number 9), upholding the internment of Japanese-Americans, including U.S. citizens, during the Second World War; and

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978, number 12), in which the decisive opinion of Justice Lewis Powell brought about 45 years of chicanery about race-based university admissions in the name of “diversity.”

One would expect conservative and progressive legal scholars to differ widely on the Court’s worst decisions, but we think it striking that progressives would almost certainly rank Dred Scott, Plessy, Buck, and Korematsu as among the justices’ worst opinions—while they are almost certainly undisturbed by Bakke and its progeny, and fear it will be overturned in the Court’s current term. To be sure, many jurisprudential liberals disagree with conservatives about whether there is a constitutional right to abortion, but many progressives have long recognized that Roe had no sound basis in the Constitution.

The second group of cases in our Dishonor Roll comprises five opinions in which the Court invented rights nowhere to be found in the Constitution, or (in one case) presaged a jurisprudential hierarchy in which certain “preferred freedoms” of the left would outrank others, notwithstanding their equal status in the Constitution. (Dred Scott, Roe, and Casey could all fit in the “invented rights” group too, of course.) In chronological order, the first of these “invented rights” cases, which ultimately gave its name to a whole era in Supreme Court history, is Lochner v. New York (1905), in which the majority (per Justice Rufus Peckham) averred that a substantive reading of the Due Process Clause protected a “liberty of contract” capable of defeating “unreasonable” regulations of employer–employee relations. (We are certain that some of our more libertarian respondents do not disapprove of Lochner, yet overall it came in at number 14.)

Conservatives also rank three cases involving privacy and LGBT rights as among the Court’s worst decisions: Griswold v. Connecticut (1965, our number 6), Lawrence v. Texas (2003, number 10), and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015, number 5). The first two rulings invalidated statutes prohibiting the use of contraceptives and homosexual sodomy, and the third required legal recognition of same-sex marriages. Some of our respondents are surely opponents of same-sex marriage; few would wish to criminalize anyone’s sexual activity; fewer still (perhaps none) would seek to restore the prohibition of contraceptives. We surmise that our respondents’ criticism of these decisions probably has less to do with the outcomes and far more to do with the fanciful legal reasoning used by the justices who reached them.

A final case in this group is United States v. Carolene Products Co. (1938, our case number 18), an otherwise obscure case well-known among scholars for its seminal footnote 4, where Justice Harlan Fiske Stone sketched a jurisprudence of the future in which the Court’s usual presumption of the constitutionality of challenged laws and policies would be relaxed, or even substantially reversed, in cases involving civil liberties and “insular minorities.”

The third group in our Dishonor Roll consists of those opinions in which the Court, in our scholars’ view, failed to enforce constitutional rights or other limits on government power (a category into which Plessy, Buck, and Korematsu could also fall). One case here made the top ten, Wickard v. Filburn (1942, our number 7). The majority opinion expanded Article I, Section 8’s Commerce Clause to include practically all economic activity, thus opening the door to permit Congress to regulate almost anything it desires. Acting similarly with respect to state power, Home Building & Loan v. Blaisdell (1934, number 15) gutted the protections of the Contract Clause of Article I, section 10, while Kelo v. City of New London (2005, number 17) made a mockery of the “public use” requirement that the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment imposes on the use of eminent domain.

A final case, and the oldest in this group, is the opinion of Justice Samuel Miller in the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873, our number 11). Whatever their views of the decision’s holding that Louisiana could establish a corporate monopoly in the butcher trade in New Orleans, Miller’s opinion is widely viewed as having fatally obscured the intended meaning of the then-new Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause.

The last group of cases identified as among the Twenty Worst are those in which the majority, in our scholars’ view, misconstrued the religion clauses of the First Amendment: Everson v. Board of Education (1947, our number 13), Engel v. Vitale (1962, number 19), Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971, number 16), and Employment Division v. Smith (1990, number 20). The Everson opinion of Justice Hugo Black, while upholding a New Jersey town’s reimbursement of parents for bus fare to their children’s parochial schools, laid down a “strict separationist” understanding of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause that many scholars today recognize as textually and historically insupportable. Engel took the predictable next step, following Everson’s logic, of overturning the practice of teacher-led prayer (however nonsectarian) in public schools; and Lemon established an unworkable, ahistorical three-part test for assessing challenged legislation under the Establishment Clause. Finally, Smith—a case whose low score shows how much it still engenders disagreement among conservatives today—made the final position in our Worst Twenty for Justice Antonin Scalia’s rejection, in a case involving religious use of the drug peyote, of the jurisprudence of exemptions from generally applicable laws under the Free Exercise Clause.

Reasonable people, including legal scholars, disagree about which Supreme Court decisions are to be praised and which are to be condemned. And yet it seems clear that history will not judge well those jurists (and legislators) who have denied that all persons are created equal and deserve the full protection of the law. Nor will it be kind to justices who invented rights not found in the Constitution, failed to protect those that are in it, or misunderstood the proper relationship of religious faith and public policy under our Constitution.