Capitalism has brought greater economic wealth and cultural freedom to more people than any other system in the history of man.

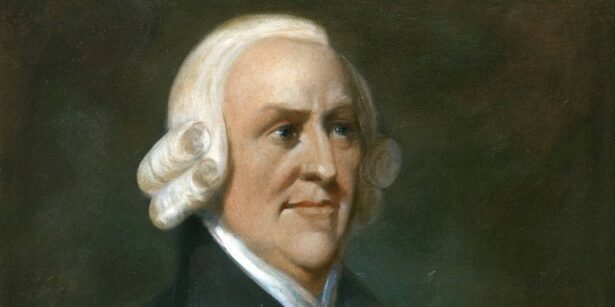

The Cooperative Capitalism of Adam Smith

Important people in history are typically commemorated on their birthdays. But some have unknown birthdays, making that tradition difficult to honor. For example, Adam Smith, history’s most famous economist, illustrates such difficulties. Some sources list his birth as June 16, 1723 while others put it on June 5 of that year (due to the use of different calendars). Still others say we don’t know when he was born but give one of those dates as when he was baptized, of which we do have a record.

Despite that problem, we are certain that this year is the tricentennial of Adam Smith’s birth, making this a very appropriate time to remember him and celebrate his valuable insights.

I anticipate quite a few articles about Smith’s contributions to economic understanding for his 300th anniversary, such as his articulation of how the “invisible hand” of market interactions can coordinate a society based upon liberty—i.e., private property and voluntary exchange—more effectively than the coercive power of the state. To quote Smith, “By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.” So I thought I would wander a bit from the well-beaten paths and consider his masterful preemptive rebuttal to decades of claims that voluntary market arrangements (or capitalism, a term used to falsely imply that only the owners of capital gain from the system) represent a dog-eat-dog jungle of a society.

Such claims have circulated long enough to become embedded in society. For instance, several songs include such phrases. But my favorite example comes from a Cheers episode, when Woody asked Norm how things were. Norm responded, “It’s a dog-eat-dog world, Woody, and I’m wearing Milk-Bone underwear.” Yet, even when it is used in a humorous way, the phrase is striking to me because I don’t know anyone who has ever seen a dog eat another dog, and making an analogy to something that doesn’t happen is a remarkably weak reed to support anything like a logical argument. In fact, the Oxford English Dictionary traces the phrase “dog eat dog” back to 1794, but notes that it is a corruption of the Latin “canis caninam non est,” which asserted the opposite: that dog does not eat dog.

If, despite that inadequacy, such mischaracterizations of market arrangements can achieve acceptance, it gives those who wish to advance their agendas by violating people’s property rights a lever to dismiss the mountains of evidence in favor of capitalism’s voluntary social coordination as instead a vicious, ugly, harmful process.

Adam Smith’s prebuttal to such assertions comes in the most famous book in economics—his Wealth of Nations—which has remained in print since the year American colonists issued the Declaration of Independence. It appears in Book 1, Chapter 2, so even a minimal effort to understand his reasoning would get a reader that far. Further, one of the book’s most famous quotes sits as a lure to attention in the middle of the discussion (“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages”).

There, Smith noted that dogs do not have property rights, as do humans (“Nobody ever saw one animal by its gestures and natural cries signify to another, this is mine, that is yours”). They do not have “the facilities of reason and speech” which would enable them to negotiate and make contracts. They do not exchange with one another (“Nobody ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange…with another dog”). Dogs, consequently, do not produce for one another, benefitting each other based on exchanging the fruits of their different talents and specialization (“for want of the power or disposition to barter or exchange,” they “do not in the least contribute to the better accommodation and conveniency of the species,” and so each “derives no sort of advantage from that variety of talents with which nature has distinguished its fellows”).

Animals’ absence of any rights beyond their own ability to deter other animals’ invasions means they do not have the private property rights protections that Herbert Spencer described as “an insistence that the weak shall be guarded against the strong,” and John Locke called the reason “man…is willing to join in society.” And ignoring why people, unlike animals, unite in society is fatal to any convincing equation of a system of voluntary arrangements to a “dog-eat dog” jungle.

The absence of exchange and the production for others among animals creates a zero-sum world, in which what one wins, the other loses. Competition restricted to such circumstances can indeed be a vicious, do-or-die struggle. But that is not the competition of markets. That is the competition of war, motivated by the desire to override other peoples’ rights.

“I win, you lose” behavior traces back to given, limited resources, which is not the situation people face under capitalism, which has done more than any other social “discovery” to replace such behavior with win-win possibilities.

People, however, who are protected by private property rights and the derivative right to contract, are united by the vast mutual benefits production and exchange with one another can make from our dramatic differences in interests and abilities. Instead of a zero-sum game, market competition produces an incredibly positive-sum “game” in which each benefits him- or herself by finding more and better ways to benefit others, which George Reisman recognized as producing a situation where “one man’s gain is positively other men’s gain.” And it comes through the ability to create and exchange with others, which Smith noted, is “common to all men, and to be found in no other race of animals,” which is why for man, “the greater part of his occasional wants are supplied by…treaty, by barter, and by purchase,” which, in turn, “gives occasion to the division of labor,” and the massive expansion of output that makes massive expansions of consumption possible.

It makes no sense to portray voluntary cooperation which must respect participants’ rights as a desperate battle for survival, where “anything goes.” Such “I win, you lose” behavior traces back to given, limited resources, which is not the situation people face under capitalism, which has done more than any other social “discovery” to replace such behavior with win-win possibilities. In Smith’s words, “Among men…the most dissimilar geniuses are of use to one another…where every man may purchase whatever part of the produce of other men’s talents he has occasion for.” Provided that people’s ownership of themselves and their production is respected, their voluntary arrangements are the means by which all gain. And that man-serving-man world is a far cry from a dog-eat-dog world.

Beyond demolishing the idea that markets represent a dog-eat-dog jungle (which is, in fact, a far closer description of government “solutions,” backed by their power to coerce people against their will), Smith offers other insights into what markets do represent and accomplish. These also reveal how different voluntary, private-property-based market arrangements are from such epithets. To avoid overly belaboring the point, consider just four of my favorite Smith quotes on the subject:

The uniform, constant and uninterrupted effort of every man to better his condition…is alone, and without any assistance, not only capable of carrying on the society to wealth and prosperity, but of surmounting a hundred impertinent obstructions with which the folly of human laws too often encumbers its operations.

In the midst of all the exactions of government…capital has been silently and gradually accumulated by the private frugality and good conduct of individuals, by their universal, continual, and uninterrupted effort to better their own condition. It is this effort, protected by law and allowed by liberty to exert itself in the manner that is most advantageous, which has maintained the progress.

Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice; all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things.

All systems either of preference or of restraint, therefore, being thus completely taken away, the obvious and simple system of natural liberty establishes itself of its own accord. Every man, as long as he does not violate the laws of justice, is left perfectly free to pursue his own interest in his own way, and to bring both his industry and capital into competition with those of any other man.

The first of my favorites emphasizes that rather than producing a jungle of harm, self-interest, subject only to the need to respect property rights and live up to voluntarily agreed contracts, is capable of producing wealth and prosperity, combined with the recognition that government is often the problem rather than the solution. The second reinforces the first, emphasizing the fact that competition in markets leads to good conduct, not the vicious conduct opponents of economic freedom use as a false premise for their desired “reforms.” The third continues the theme, with a focus on the main problem in this regard, which is government failure to protect property rights and voluntary arrangements, which is its primary if not only role that serves to advance what the Constitution called General Welfare. The last summarizes the advantages of “the obvious and simple system of natural liberty” and its consistency with justice, which cannot be the case of government alternatives that violate property rights and liberty.

Adam Smith’s tricentennial justifies renewed consideration of his wisdom about mutually-beneficial social cooperation. It is particularly important at a time when governments have long honored his insights far more in the breach than in the observance. Since the idea of markets as “dog-eat-dog” jungles has played a role in that destructive result, perhaps we should honor Smith by recognizing that such calumny is entirely inaccurate, and so take away a false premise that has underlain (with apologies to Robert Frost) so many wrong roads that should have been less traveled by.