The Fourteenth Amendment's Ambiguous Section Three

The current effort to disqualify Donald Trump under Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment makes for high-stakes politics, but bad history. Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment disqualified certain people from serving in the House or Senate, or as a presidential elector, if they had betrayed their oath of fealty to the United States and joined the rebellion during the American Civil War. Whether Section Three accomplishes anything more remains unclear as a matter of both history and constitutional text.

To date, the debate over Section Three has taken place without any systematic investigation of either the drafting process or the ratification debates. Scholars, lawyers, and judges have been flying (historically) blind—a situation I hope to change.

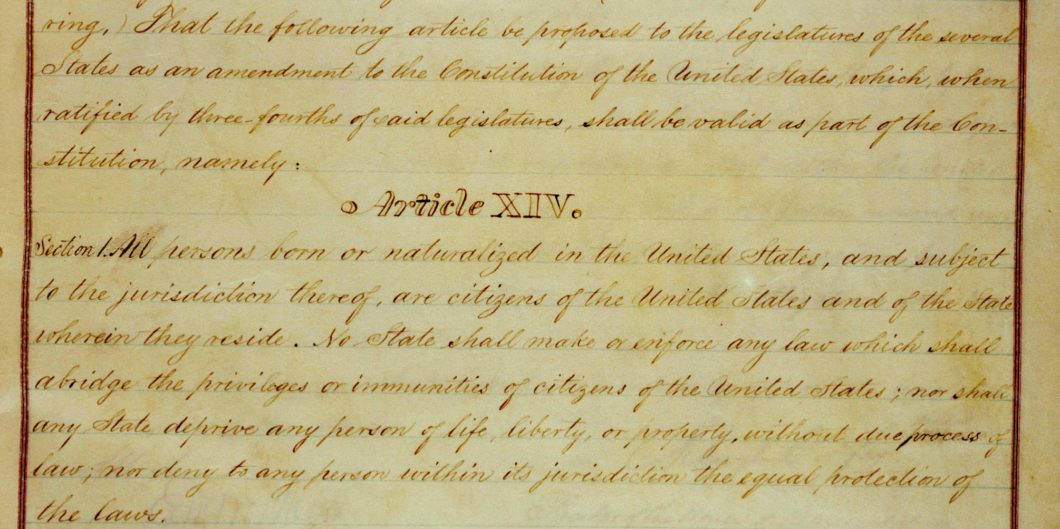

The text declares that “[n]o person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, . . . who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States . . . to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion.” The text does not expressly (1) apply to future rebellions or insurrections, (2) apply to persons elected as President of the United States, (3) apply to persons seeking to qualify as a candidate for the Presidency, or (4) indicate whether the enforcement of Section Three requires the passage of enabling legislation.

The omission of express language on these issues is significant because prior publicly announced drafts did expressly apply to present and future rebellions, did expressly name the office of the President of the United States, and did expressly bar certain persons from either holding or qualifying for office. For example, the very first draft proposed:

No person shall be qualified or shall hold the office of President or vice president of the United States, Senator or Representative in the national congress, or any office now held under appointment from the President of the United States, and requiring the confirmation of the Senate, who has been or shall hereafter be engaged in any armed conspiracy or rebellion against the government of the United States.

The final draft of Section Three omitted the express reference to being “qualified,” the express reference to the office of the President of the United States, and any reference to future rebellions (those “hereafter”). Instead of disqualifying someone elected President by the Electoral College, the final draft prohibits any oath-violating rebel from serving in the Electoral College.

The public was well informed about Section Three’s development, including the debates about various drafts. Unlike the secret debates of the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, newspapers in 1866 published the debates and activities of the 39th Congress on a daily basis. The people were well informed about what was proposed, what was abandoned, and congressional understanding of what was finally passed. These same newspapers published commentary on the various drafts of Section Three and the later ratification debates in the state assemblies.

In a new article, I explore all of this reporting and commentary in depth. I conclude that although the public shared a common understanding of some aspects of the text, other aspects—especially those most relevant to the candidacy of Donald Trump—remained unclear and sharply debated.

For example, Republican Senator Lyman Trumbull publicly explained that this portion of the Fourteenth Amendment was “intended to put some sort of stigma, some sort of odium upon the leaders of this rebellion, and no other way is left to do it but by some provision of this kind.” The historical record abundantly supports Trumbull’s explanation as the common public understanding of the text: Section Three applied to a still-living group of former rebels whose betrayal of the country had caused more than 600,000 deaths and misery and destruction on a level beyond anything the country had previously experienced (or has since).*

Whether the text applied beyond this unique historical event is unclear. Some framers and ratifiers thought it included future rebellions, others did not. Dissenting members of the Indiana ratifying assembly, for example, specifically criticized Section Three because it did not apply to future insurrections. Similarly unclear was whether the text automatically disqualified certain persons, or whether Congress would first have to pass enforcement legislation establishing procedures that would preserve every person’s right to judgment by an impartial tribunal.

In his speech introducing the Joint Committee’s draft of the Fourteenth Amendment, Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens declared that the third section “will not execute itself.” Stevens later insisted that the text would not prevent rebels from becoming President “unless in the prescription of proper enabling acts.” During the ratification debates in Steven’s own Pennsylvania, Thomas Chalfant also noted the necessity of congressional legislation to enforce Section Three. As Chalfant explained to his colleagues, “You will say, and say properly, that in order to make this section of any effect whatever, the guilt must be established. I grant it.” That could only be done, Chalfant noted, by legislation passed pursuant to Section Five of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Section Three ensured a loyal President and Vice President by ensuring that only loyal electors would cast their votes for these positions. This was enough for the moment.

Finally, it remains unclear whether there was any consensus regarding the text’s application to the office of the President of the United States. Prior drafts had expressly named “the office of President or vice president of the United States,” but the final draft did not. Instead, the text of Section Three takes a different route to preventing a former rebel from being elected President. Immediately following its prohibition of certain persons holding a seat in The House of Representatives or the Senate, Section Three then prohibits certain persons from serving as an “elector of President and Vice-President.” These three express disqualifications are then followed by a catch-all reference to “any office . . . under the United States, or under any State.” This structure suggests that no person, rebel or not, is precluded from holding the high office of the President if they are elected by a sufficient number of loyal electors in the Electoral College. The catch-all phrase then covers the remaining lower-level offices in the executive branch and in the states.

This is precisely how one of the most respected lawyers in the House of Representatives, Reverdy Johnson, first read Section Three. During the congressional debates, Johnson criticized Section Three for its failure to disqualify rebels from holding the seat of President or Vice President of the United States. When a colleague interjected and claimed that the office of President fell within the catch-all phrase, Johnson conceded the point. But Johnson further explained that it was the text itself that prompted his initial reading. According to Johnson, “I was misled by noticing the specific exclusion in the case of Senators and Representatives.”

Lawyers will recognize Johnson’s application of a well-known rule of construction called expressio unius est exclusio alterius—the expression of one thing means the exclusion of another. Members of the public may not have known the Latin, but they likely shared Johnson’s initial intuitive reading of the text. Johnson himself may have been “corrected,” but the brief exchange went unreported in the press. In fact, I have not discovered a single example of anyone during the ratification debates suggesting that Section Three disqualified anyone from holding the office of the President of the United States.

Some scholars argue that it would be absurd to read Section Three as not preventing a former rebel like Alexander Stephens from being President. But there is no reason to think it would have been absurd to anyone in 1868. The proposed Fourteenth Amendment contained a wealth of provisions guarding the office of the President. Section One prevented southern states from suppressing pro-Republican political speech. Section Two prevented the South from expanding their numbers in the Electoral College (unless they gave pro-Union Black Americans the right to vote). Finally, and most crucially, Section Three ensured a loyal President and Vice President by ensuring that only loyal electors would cast their votes for these positions. All of this was enough for the moment.

And that particular moment was all that the text unambiguously addressed. Section Three was designed “to put some sort of stigma, some sort of odium upon the leaders of this rebellion.” Whether the public understood the text as involving anyone or anything beyond the still-living leaders of that rebellion remains textually unresolved and historically unclear.

*Editor’s note: An earlier version cited Jacob Howard instead of Lyman Trumbull. The argument remains unchanged as both were influential Republicans whose comments were published in the press.