America's history of appreciating the military is worth keeping, but the country doesn't need the military in politics.

Towards a Politics of Truth

Philip Wallach has posed a worthwhile challenge to my argument that a return to the “politics of truth and virtue that built the West” will help us restore our political order. In his Law & Liberty essay, “Do We Need a ‘Politics of Truth,’” Wallach rejects my distinction between a politics of truth and a politics of utility as a “category error.” Instead, he defends a conception of politics “as its own sort of endeavor,” namely, “the search for common actions.”

In his defense of politics for politics’ sake, Wallach justifiably mentions, twice, that it remained “unclear” what I meant by “the politics of truth.” In this essay, I will take up Wallach’s challenge to clarify my meaning. And in doing so, I will explain why the embrace of politics as its own autonomous sphere—an example of what I meant by “the politics of utility”—is both impossible and undesirable.

The Denial or Affirmation of What Is Given

Politics does have its own sphere, as Wallach maintains. It has its own realm of responsibility. The ends of politics are justice and peace. But it testifies to the philosophic nature of politics that the foundational text of the Western canon is Plato’s Republic, in which the interlocutors ask: what is justice? Answering this question requires investigation into the nature of the human person, of what he is owed and what he owes to himself, to others, and to God.

It might seem strange or imprudent to jump from the definition of justice to a consideration of the duties we owe to God. But it is a necessary part of orienting our self-understanding in a self-governing community. It is an elementary point that we did not give ourselves life. Existence is given to us. And we must decide whether to accept what is given or to reject it.

The atheistic and nihilistic revolutionaries who populate Dostoevsky’s novel Demons, for example, reject what is given and leave tragedy in their wake. They burn everything to the ground. Dostoevsky said of them: “These people imagine that nature and human society are otherwise than God made them and than they actually are.” Those who reject what is given affirm Sartre’s dictum that existence precedes essence, that we came from nothing and can make of ourselves whatever we will.

On the other hand, we can accept that essence precedes existence, or, in related terms that are perhaps more understandable, that mind precedes matter. That is to say that there is a divine intelligence that created the human person according to a providential plan and provided a universal, objective, and immutable law for his flourishing. And the substance of this law is made available to human beings by reason and revelation.

Contemporary liberals reject a given order of things, that is, a prior, universal truth capable of limiting our attempts at self-assertion. Self-creation is the guiding ideal of liberal thought. Danielle Allen, for example, whose recent book I reviewed for Law & Liberty, writes that liberalism aims at “self-creation.” This means that we must make individuals “maximally autonomous.” Samuel Moyn, moreover, calls “self-creation” the “highest liberal value.”

Self-creation calls for the abolition of natural limits. The willful transgression of these limits will not end well. The twentieth-century English historian Christopher Dawson observed that efforts to master nature through scientific and technological innovation turn into efforts to master human nature. Patrick Deneen describes these two aims—mastering nature and human nature—as two stages in the development of liberal ideology.

But to finally exercise a purely man-made creative power unbounded by the limits of religion or biology we must not merely reject nature but annihilate it. New explorations into augmented reality exemplify this tendency. Elon Musk’s Neuralink brain chip, for example, works by “replacing a chunk of your skull with a smartwatch.” Musk has presented the brain chip as a means by which to improve the lives of the paralyzed. The restoration of human functionality where it has been diminished is a laudable—and humane—goal. But this is not Neuralink’s sole purpose. Neuralink co-founder DJ Seo has described the project as an “engineering challenge,” to alter the brain so that we can “learn kung fu” like Neo in “The Matrix.” In other words, the goal is to make us less human and more like computers. Musk claims this is the only way to keep up with artificial intelligence. But this reasoning seems to prove Dawson’s point that the drive toward self-creation requires annihilation, since we must abolish all prior limits, human and divine, if we are to create ourselves anew.

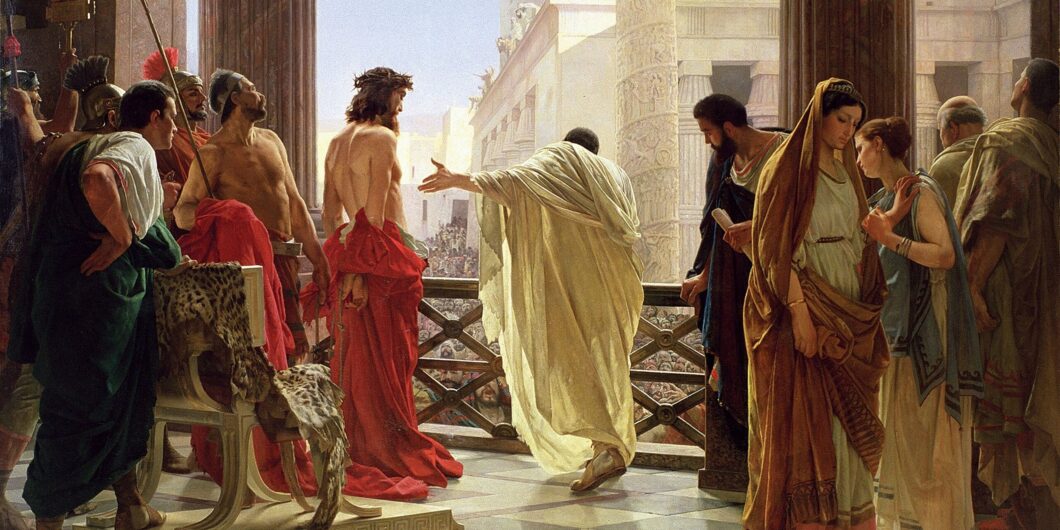

The affirmation of what is given provides us with a better, more humane alternative. And this is characteristic of what I would call the politics of truth. In the trial of Jesus before the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, Pilate famously asked, “What is truth?” In this instance, Pilate plays the part of the skeptic, the pragmatist, and the political realist. Liberalism, as a political doctrine, plays this same part. It disregards the question of truth as too burdensome to become an object of political deliberation. Like Pilate, it puts the question of truth aside and puts consideration of utility, or advantage, at the center of political life.

Utility at the Service of What?

Leon Kass stated: “Utility, like the things that are useful, is a subordinate and subservient matter, always pointing to something that is being served.” Pilate deferred to the people. He sent an innocent man to death to save his own political hide. This decision was useful, or advantageous, for Pilate, insofar as it helped him avoid a riot and the wrath of Caesar. It helped him preserve his power. He faced the truth, and he rejected it, opting to make decisions based on pragmatic political calculations. And this is what tends to happen. If the politics of utility does not serve truth, it will serve something else, something worse, whether power, license, greed, vengeance, lust, or any other partial passion or motive.

Putting the question of utility at the service of truth is the best way to place limits on politics, to prevent politics from devolving into barbarism. And this insight does not contradict our Western and American heritage. It flows from it. For example, in a letter to James Monroe, James Madison argued that the economic interest—or utility—of the many is not the standard of right and wrong in political affairs. Instead, it is the notion of “ultimate happiness … qualified with every necessary moral ingredient” that is the standard of right and wrong.

A spiritual reorientation is necessary to revive the moral and political life of the West.

Lest anyone think this quote is an anomaly, George Washington, in his inaugural address (ghostwritten by Madison, his closest advisor in the first days of his presidency), stated that “national policy will be laid in the pure and immutable principles of private morality.” Elsewhere in the speech, he equated these principles of private morality with “the eternal rules of order and right, which Heaven itself has ordained.” In other words, Washington and Madison, at least, did not think that politics was an autonomous sphere operating by its own rules, its own logic, its own “public morality.” They thought the same “eternal rules of order and right” that applied in the private sphere applied in the public sphere as well.

Wallach asks whether a politics of truth might lead us to “stipulate that a particular group of people is in full possession of Truth.” Wallach rightly asks, “How are we supposed to ascertain the truth, and how should we bring it to bear in addressing the practical questions that politics must answer?”

My response is a conservative one. The politics of truth affirms not only what is given by the order of nature and the constitution of human nature but also what is given by our civilizational heritage. It is not my own personal wisdom I am drawing upon, but the wisdom of the ancestors. Graham McAleer, a frequent contributor to Law & Liberty, coauthored a book with Alexander S. Rosenthal-Pubul, entitled The Wisdom of Our Ancestors. These authors rightly associate conservative humanism with the Western tradition, namely, Greek philosophy (oriented toward the logos), Roman law, and the theology derived from the Hebrew and Christian scriptures. The Western tradition, however, is not simply grounded in the dynamic interactions between these strands of moral, political, and religious thought. It is grounded, the authors write, in a “trinity of traditions,” namely, religion, family, and education.

The Preservation of Tradition

If we are going to describe what a politics of truth looks like, then I think this is a good place to start. The politics of truth does not entail an allegiance to a particular political form or even particular policy prescriptions. Instead, the politics of truth seeks to preserve and promote those institutions—religion, family, education—that facilitate a humanizing moral and political culture.

Of course, there are plenty of policy proposals consistent with strengthening family and education in our country. There are ways to make it easier for families to raise children, to dismantle a billion-dollar pornography industry that is rife with abuse, trafficking, and drug addiction, not to mention making dating and marriage ever more difficult. There are ways to promote classical and Christian K-12 schools and to rid our educational environment of the scourge of totalizing critical theories and gender ideologies. Such policies are being introduced in states across the country. Pro-family policies and educational reform serve truly good ends, namely, the strengthening of institutions that produce good husbands and fathers, wives and mothers, citizens, and human beings.

Wallach acknowledges that politics is a “practical science, aimed at securing actions conducive to the good of the community.” But we must define what is good. Wallach argues that politics is about “helping people achieve their goals.” But which goals? The very question demands moral judgment, which distinguishes between true and apparent goods. Wallach admits as much when he writes that the political process “when healthy, is shot through with moral, aesthetic, and prudential judgments about what is worth doing.”

Wallach maintains that “our lack of agreement on fundamental religious truths does not impair us” in our political deliberations. I think this might be the point on which we disagree most. We are faced with a choice—a primordial choice between affirmation or rejection of life—that guides our understanding, deliberations, and pursuits in political community. Of the “trinity of traditions,” religion is the one that most directly relates to this affirmation or rejection of life.

Our Most Important Tradition

A good human life is one of meaning and purpose, which is why the fostering of religious well-being is—partly, though not wholly—a matter of political choice. The political realm should not be responsible for the salvation of souls. But it should recognize that we have souls. Such a recognition both ennobles political action, by putting it in the service of persons who are made in the image of God and who possess inherent dignity, and limits political action, by recognizing that salvation is beyond its jurisdiction.

As I mentioned in my piece, “Saving Ourselves from Party Rage,” people are looking to politics for meaning. They are doing so, because they are less likely to find meaning in the traditional, non-political institutions of religion, family, and education. And this is responsible for much of our heated political rhetoric. People, who by many of today’s economic measures are better off than ever before, are asking themselves what is wrong with the world and pointing, increasingly, to systemic problems brought to the attention of the American public by the New Left in the 1970s, namely, racism, patriarchy, and capitalism. By embracing the “causes” of anti-racism, feminism, or socialism, individuals express their opposition to the corrupt systems they think are responsible for society’s ailments. In so doing, they locate the sources of evil in human life and find meaning in combating them.

Anti-racism, feminism, and socialism are ideologies. They provide clear-cut, systematic, overarching narratives about what is wrong with the world and how to fix it. As such, they function as substitutes for religion, as writers from John McWhorter to Christopher Rufo have argued. These ideologies are by no means strictly political. They are totalizing, adamantine, and unforgiving. They brook no dissent. And they are a response to spiritual and moral yearnings more than political circumstances.

The decline of Christianity facilitates the growth of these ideologies. And the growth of these ideologies portends the continued decline of Christianity. Religious “nones,” consisting of atheists, agnostics, and “nothing in particular,” are now the largest religious group in the US (28%), outnumbering Catholics (23%) and Evangelical Protestants (24%). Although 90% of Americans were self-described Christians in 1972, that number fell to 64% in 2020 and could fall as low as 35% by 2070.

For centuries, Christianity has served as the supranational life source of Western civilization, fostering unity in spiritual and moral belief, while allowing for a diversity of political and economic forms. Christianity teaches that sin, which is responsible for the evil in the world, can be found in each human heart and can be overcome by a combination of grace and moral effort. It teaches that man and woman are equal before God regardless of race or ethnicity. It teaches that the moral law applies to all human beings. Both the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures affirm that mankind and the created order are good. They both lead us away from the assertion that one group, one class, one race or ethnicity, or one “system” is the source of all wrongs in the world. Although Christianity’s historical record is by no means unimpeachable, and although it exists today in myriad denominational forms, it tends to impede utopian projects—by locating perfection in the other world, rather than this one. And in so doing, it preserves freedoms against which ideologies militate.

We are religious beings as much as we are political beings. And the political realm must be as attentive to that fact as it is to the fact that we need safe drinking water, reliable infrastructure, and national defense. We must investigate the truth of the matter. We are religious beings who have lost meaning and purpose after centuries of chasing the dream of self-creation. A spiritual reorientation is necessary to revive the moral and political life of the West. A politics of truth will not achieve that reorientation. But it can help.