The very ideologues who claim that we must be kind are not inclined to be kind to their political opponents—for with them, compassion is merely rhetorical.

Unmasking the Perils of Ideology

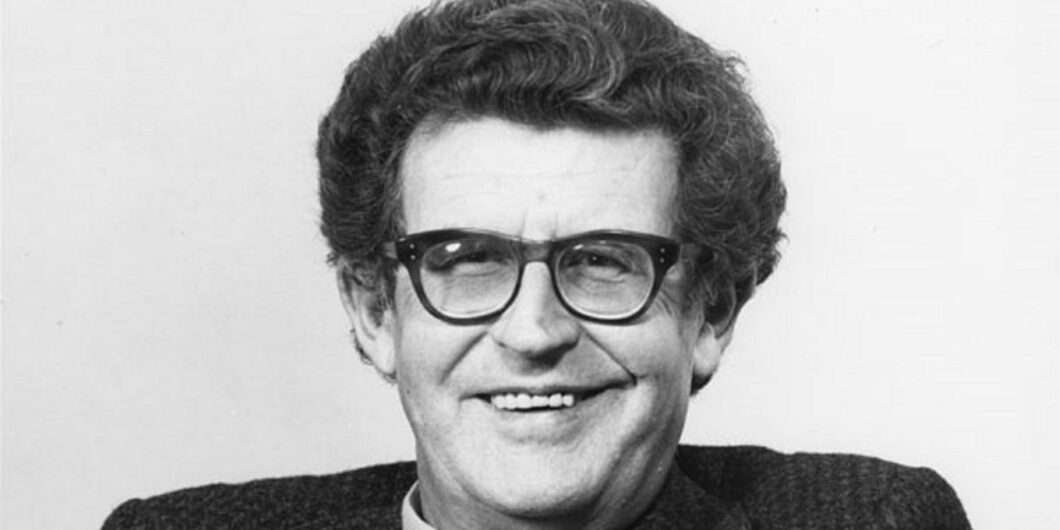

“Ideology is the purest possible expression of European civilization’s capacity for self-loathing,” wrote Kenneth Minogue in his classic book Alien Powers: The Pure Theory of Ideology, published in 1985. These words resonate today as ideologues stir resentment and anger against the practices of Western civilization and its individualistic and enterprising individuals. To the ideologue, the modern West is an oppressive system from which the exploited require emancipation. The ideological assault against the West and its practices is one of the most formidable challenges facing those who cherish our free way of life. To understand ideologies and appreciate the dangers they pose, Minogue—who passed away ten years ago this summer—is a thinker worth reading.

Born in 1930, Minogue was educated at the University of Sydney and the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), where he was influenced by the sceptical and critical outlook of John Anderson, as well as the sceptical and conversationalist views of Michael Oakeshott. These influences made Minogue a perfect candidate for Oakeshott’s additions to the government department at LSE, where Minogue established himself as an academic for many years. Minogue’s career at LSE was complemented by an active public intellectual life. He championed conservative ideas and the Western free way of life during the troubles of the ’60s, through Margaret Thatcher’s leadership of Britain’s Conservative Party, and in the aftermath of the New Right’s dominance over politics in the West.

A few years after his appointment at LSE, Minogue published what is probably his best-known work, The Liberal Mind (1963). In that book, republished by Liberty Fund in 2001, he dissected the mindset of the modern liberal and addressed what would become his central concern: the ideological challenge to Western civilisation. The book was published in an intellectual context where thinkers such as Daniel Bell, Raymond Aron, and Edward Shils were proclaiming the End of Ideology in the West. For these thinkers, the experience of the Second World War, disenchantment with Soviet communism, and the collapse of faith among intellectuals and politicians after witnessing ideology in action had created the conditions for its end. Minogue held no such celebratory mood.

In his book, Minogue asserts that ideology is still very much alive within modern liberalism. He argued that modern liberalism had become discontented with the modern world due to the various forms of suffering afflicting both individuals and society. In response, modern liberalism turned to technical knowledge to prescribe solutions to these problems through state action, aiming to achieve an ideal society free from suffering. This shift marked a significant departure from the traditional emphasis on individual freedom within classical liberalism, with its modern counterpart now embracing what Minogue termed “liberal salvationism.” Liberal salvationism, according to Minogue, reflects the belief that through state intervention, human conduct can be reformed, leading to the emergence of a perfect and redeemed world.

Modern liberalism sought sustained intellectual and policy support for its campaign to redeem the modern world, and it found this support in universities. According to modern liberals, universities are tasked with contributing to the perfectionist ideal through their research and policy work, providing solutions to address suffering situations. This instrumental role assigned to universities by modern liberals stood in stark contrast to what Minogue considered to be the proper role of these institutions of higher education. In The Concept of a University (1974), Minogue, echoing Oakeshott, argued that academic inquiry within universities should not be driven by teleological concerns, which would make the institution susceptible to government and ideological intervention. Instead, he contended that academic inquiry should have a non-instrumental role in the thoughtful and intellectual pursuit of truth.

The pursuit of a perfect world extended beyond domestic politics and civil institutions such as the university; it also manifested in modern liberalism’s early support for nationalist ideologies that gained traction in Asia and Africa after World War II. In Nationalism (1967), Minogue, following in the footsteps of his colleague Elie Kedourie, sees nationalism as a grievance-seeking ideology that promises salvation through the nation. According to the nationalist perspective, salvation entails political, territorial, social, and cultural unity, that equates the will of the individual with the will of the nation. Consequently, nationalists are inherently hostile to individualism and pluralism, as these concepts are seen as threats to the envisioned unity. While Minogue did not oppose decolonisation, he critiqued modern liberals for their salvationist approach and the sense of guilt that underpinned their support for what they perceived as “good nationalism.” Furthermore, Minogue chastised modern liberals for their naivety in believing that these newly formed nations would naturally evolve into liberal democracies, align with capitalism against communism, and lead to a better world.

Hostility to the modern individualist way of life is driven by a nostalgic yearning for a perfect world, a yearning that dominates modern liberals and an ever-increasing number of conservatives.

The enduring theme of ideology, present in both domestic and international contexts, constitutes a significant aspect of Minogue’s body of work. Nevertheless, the term “ideology,” coined by Destutt de Tracy during the French Revolution, has been a subject of scholarly debate, with varying connotations over time. Classical Marxists viewed ideology negatively, as representing the beliefs of the oppressor class. Later, under the influence of thinkers like Lenin, ideology acquired a more positive tone, encompassing the totality of beliefs within a society, whether from the bourgeoisie or the proletariat. Subsequently, with the work of Mannheim, ideology was given a non-evaluative connotation, being only the representation of the beliefs of individuals. However, in Alien Powers, Minogue aimed to reclaim the original negative connotation associated with the term “ideology,” while rejecting the Marxists’ oppression theme. He viewed ideology as a critical mode of thought that poses a threat to the tradition of politics of Western civilisation and its free way of life.

Minogue defined ideology in Alien Powers as “a form of social analysis which discovers that human beings are the victims of an oppressive system, and that the business of life is liberation.” In this conceptualisation, we can discern the two primary functions of ideology. First, it serves a critical function by falsifying the modern Western way of life as an oppressive system, leading ideologues to harbour an inherent aversion to the modern West with its pluralism and individualism. Second, ideology assumes a positive role by positioning itself as possessing the true knowledge to liberate individuals from this systemic oppression. Consequently, ideology presents itself as a pseudo-scientific mode of thought, offering a certain path to transform the entire system with the ultimate aim of creating a perfected community.

Minogue’s perspective helps to identify and respond to the ideological challenge faced by the modern West. First, he differentiates ideology from the broad characterisation given to it by Mannheim, where it represents the beliefs of individuals tied to their social location. According to Minogue, social location does not offer the revelatory knowledge claimed by ideologues. Instead, for the ideologue, the social context is merely a part of the oppressive system that hinders the emancipation of the oppressed. Consequently, ideology is not merely a non-evaluative description of individual beliefs, as employed within the social sciences. Rather, it unveils the oppressive nature of the modern world and charts a path toward a utopian promised land.

Second, Minogue’s approach separates ideology from the classical tradition of Western politics, which involves deliberation about the conditions to be accepted as members of a civil association. Paradoxically, ideology utilises politics as a means to an end—the end being the eradication of politics itself. Ideologues reject the inherent conflict in Western politics, as it hinders the achievement of perfection. Minogue succinctly captures this in Politics: A Very Short Introduction (1995) when he states, “Any conception of a finally perfect state is incompatible with the very activity of politics itself.” Therefore, Minogue reaffirms the autonomy and limited scope of political activity, emphasising the alien nature of ideology within the Western political tradition.

Third, Minogue underscores that ideology is a modern creation with an anti-modern purpose. This anti-modern objective involves rejecting modern societies that emerged as a result of individuals’ disposition to pursue their own desires and moral identities. Instead, ideologues yearn for a futuristic utopia rooted in the ideals of a traditionalist society, where the desires and moral identities of individuals are predetermined by the community or by some rationalist ideal.

Thus, ideology, according to Minogue, serves a critical function: identifying those doctrines that are hostile to the modern West and its political tradition. Minogue effectively employed this critical function to identify a new form of ideology that is gradually eroding the moral fabric of individuals, transforming them into servile beings. In his final book, The Servile Mind: How Democracy Erodes the Moral Life (2010), Minogue identified this ideology as the “politico-moral” ideology:

A structure of thought that rejects the narrow boundaries of the individualist moral life. … [It] presents instead a set of aspirations, support for which would begin to redeem the guilt appropriate to the way we as a civilization have developed.

The “politico-moral” is the contemporary character of modern liberalism, driven by Western guilt or self-hatred for all the supposed defects of the modern West. It purports to solve these problems with a new moral idiom, in which individual deliberations about human conduct are extrapolated to others or the state, with the goal of achieving the perfectionist dream. Minogue calls this the “servile mind.” It is evident in the ever-increasing government managerialism in every aspect of human conduct from addressing inequality to prohibiting large sodas due to their effects on obesity. Therefore, for the politico-moralist, freedom is not the silence of law as Hobbes believed, but rather individuals are freer or liberated from oppression when there is a cacophony of laws governing their conduct.

The value of Minogue’s work lies not only in identifying ideology in our contemporary times but also in understanding that the essence of ideology is hostility towards the modern West and the disposition that created it: individualism. This outright hostility to the modern individualist way of life is driven by a nostalgic yearning for a perfect world, a yearning that dominates modern liberals and an ever-increasing number of conservatives. The moral practice of individualism, where individuals deliberate about their conduct and self-realise their felicity and moral identity, is perceived as the primary obstacle to this perfect world. As a result, ideologues clamour for a harmonious society of servile minds as the necessary condition for entry into the ideological kingdom of heaven.

Minogue recognised the peril of ideology and never embraced the notion that we would witness its end. From the very beginning, efforts have been made to redeem the fall of humanity. The outcome of these endeavours has left our Western world scarred by the wreckage of ideological projects, ranging from university education to governmental ambitions like the war on poverty. It is in the aftermath of the failure of these ideological projects that figures like Kenneth Minogue can help us pick up the pieces.