On this July 4th, we should remember that the Declaration offers the outlines of a political morality suitable for all people, whatever their identity.

Why the Left Is Losing

The mainstream Left is in serious trouble in the West. In the December 2019 election, the UK’s Labour Party was trounced by Boris Johnson’s Conservatives 365-203 in seats, and 44-32 percent in the popular vote. This was the worst result for Labour since 1935.

Yet, as Matthew Goodwin recently noted on Twitter, the most recent election was also the worst result ever for the French Socialist Party of Benoît Hamon, and for the Left in Italy and the Netherlands. It was the second-worst performance since 1949 for the German Social Democrats, the worst finish for the Austrian Social Democrats since 1945, and the worst for the Finnish socialists since 1962. In Sweden, the Social Democrats sunk to their lowest level since 1908. This is more than a coincidence.

Cultural Realignment

Underlying the trend is a wider realignment of politics away from the economic conflicts of the 20th century toward the cultural battles of the 21st. Instead of just talking about state redistribution versus free markets, elections increasingly revolve around questions of immigration, national identity, and domestic security. This disadvantages the Left.

Why? Because, as David Goodhart remarked in an interview, it’s easier for right-wing parties to move left on economics than for left-wing parties to move right on culture.

That is, left-wing parties cannot move to the vote-rich zone of most electorates where the median voter—typically somewhat conservative on culture and centre-left on economics—resides. Conservatives can do so more easily as they are less beholden to libertarian economic orthodoxy than left-wing parties are to progressive cultural values.

Identity politics and multiculturalism are central motivating forces for the highly-educated activists who have dominated left-wing parties since the ’68 generation rose to prominence. These ideas tend to be considerably less popular than the Left’s economic offer, hence the bind the Left finds itself in.

Why Political Correctness Makes the Left Unelectable

Yet this alone cannot explain the inflexibility of left-wing parties. To do so requires an additional ingredient: the rise of political correctness. Political correctness functions as an emergent system that can push new ideas even when few people actually believe in them. Like the emperor’s new clothes, no one dares violate a taboo which may cost them dearly.

To be blunt, left-wing political correctness is more powerful than the right-wing variant. For instance, many social conservatives may dislike environmentalist candidates in their ranks, but dissidents on the left of a conservative party won’t have their character questioned and reputation trashed. By contrast, a left-wing politician who moves right on culture—calling for lower immigration or abolishing female-only shortlists, for instance—is likely to be accused of racism or sexism by radical online activists. This causes them intense embarrassment and, by triggering a social taboo, may lead others to pile on them to signal virtue. This can damage a person’s reputation well beyond politics. Something of this fate has befallen the patriotic leftists of Blue Labour in the UK, who are no longer welcome in Labour circles. Brexit-supporting Paul Embery, for instance, was kicked out of the Fire Brigades Union for criticizing the union’s position on Brexit. This, they alleged, made him an accomplice of the “nationalist Right” and thus a “disgrace to the traditions of the Labour movement.” No wonder few on the Left are willing to move right on culture.

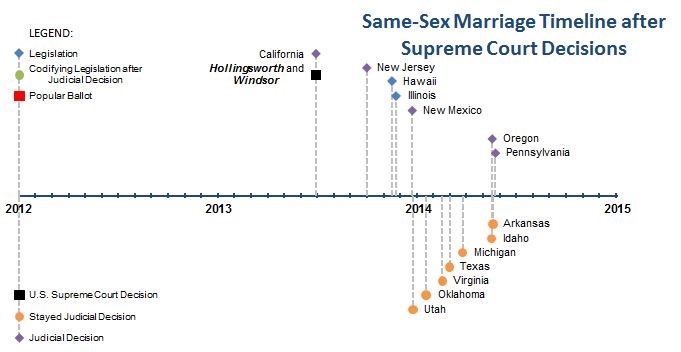

The catalyst for the change has been the post-1960s “cultural turn” of the intellectual Left, away from class issues toward the problems of disadvantaged race, gender, and sexual identity groups. Social sanctions accompanied this change of sensibility. Figure 1 shows how the term “racist” first took off in English-language books in the late 1960s. “Sexist” followed a few years later. Both enjoyed another efflorescence in the late 1980s when “political correctness” entered the lexicon.

Figure 1. Use of Identity Politics Terms in English-Language Books, 1960-2000 (Source: Google Ngram Viewer)

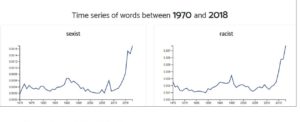

These first two great awakenings of cultural progressivism—a liberal-left fusion ideology I termed “left-modernism” in my 2004 book The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America—have been followed by another, post-2014 eruption. This has been concentrated in publications such as the New York Times which are consumed by the highly-educated metropolitan Left. In figure 2, which focuses on America, we see how a combination of editorial change and what Vox’s Matthew Yglesias calls the ‘Great Awokening’ have boosted the focus on racism and sexism. This, in turn, constrains the ability of a Bernie Sanders to question open immigration, and of other candidates to reject reparations for slavery, defend the police against charges of racism, or adopt Obama-era rhetoric on border control.

Figure 2. Editorial usage of terms “sexist” and “racist” (Source: New York Times Media Analytics, accessed August 20, 2019)

The rise of identity politics stanched discussion of the cultural anxieties of many white working-class voters, who instead find themselves the object of scorn for their apparently retrograde social attitudes. Meanwhile, identity appeals attract young, educated urbanites motivated by questions of equity and diversity. This is especially true of the largely white eight percent of the American population whom the Hidden Tribes study categorises as Progressive Activists. However, since 2014, the Great Awokening spread some of these sensibilities among the third of American whites who identify as liberal.

Realignment Within Parties

The result of the new cultural realignment has been to upend the class composition of the main parties. We see this in the steady decline in class voting across western democracies in the late 20th century. In Britain, for instance, a majority of manual working-class voters plumped for Labour between 1945 and 1975. Even after that date, at least 40 percent voted for the party, with over half backing Tony Blair’s New Labour in the 1997 election. Since then, however, Labour’s support within the white working-class has fallen relentlessly, dropping to only 20 percent among such voters by 2015.

Jeremy Corbyn continued the pattern, further consolidating the university-educated metropolitan left and ethnic minority vote while losing white working-class voters in the pivotal “Red Wall” seats of the English Midlands and North that the party had held, in some cases, since the dawn of the current two-party system. It appears that Conservative voters are now more working-class than Labour’s, something unthinkable in 1945 or even 1995.

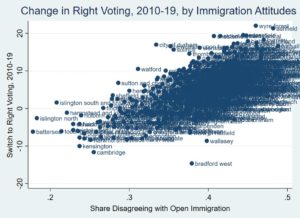

Figure 3 plots the swing to parties of the Right between the 2010 and 2019 elections by constituency. The shift of white working-class voters toward the Conservatives, as with the similar move of Midwestern blue-collar whites into Trump’s Republicans, is heavily predicted by views on immigration. As restrictionist voters in blue-collar places, such as Wyre Forest and Ashfield in the Midlands, moved toward the Tories, pro-immigration liberals in London-area seats like Battersea and Islington, or university towns like Cambridge, shifted to Labour or the Liberal Democrats.

Figure 3. Constituency voting shifts between 2010 and 2019 by immigration attitudes (Source: UnHerd Britain)

In continental Europe, most countries use a proportional representation electoral system which results in a large number of political parties catering to many political tastes. Despite the volatility and fragmentation, there has been an unmistakeable increase in populist right vote share. The 2015 Migration Crisis in particular gave right-wing populist parties a boost. European Union data shows that immigration into the European Union from outside Europe began to rise above half a million in 2013, eventually reaching two million during the height of the 2015 asylum wave. Concern over immigration rose in tandem with the numbers, with the Eurobarometer recording a steady increase. By late 2015, nearly 60 percent of survey respondents said immigration was the leading issue facing the EU. James Dennison and his colleagues found a significant relationship between immigration levels, concern over immigration, and populist right support in nine of ten western European countries between 2005 and 2016.

While centre-right parties have been constrained in the past due to pressure to maintain a cordon sanitaire against the populist right and its issue agenda, this has faded over time. In the Netherlands, Mark Rutte asked immigrants to “act normal or go away.” This burnished his nationalist credentials, helping him win re-election. In the UK, Theresa May and Boris Johnson, both of whose sympathies leaned toward remaining in the EU prior to 2016, subsequently embraced the Brexit cause, winning voters back from the populist right UKIP and Brexit Party. In Austria, Sebastian Kurz’s tough talk on immigration and integration helped him win over many populist-right Freedom Party voters. France’s Emmanuel Macron has taken a hardline stance on asylum seekers and has run afoul of progressive norms on several occasions, as when he advised African women to have fewer children. Overall, the rise in concern over immigration plays to the strength of the Right, which is trusted more on this issue than the Left.

The Exceptions

There are some countercurrents. The Left won in Portugal’s election, though the country’s small Muslim immigrant population arguably makes it different from other western European countries. The socialist PSOE managed to hang on in coalition in Spain despite a surge in support for the populist-right Vox, which won 15 percent of the vote in November 2019.

In some cases the Left can move right on culture, and when it does, it often succeeds. In Denmark, the Left has been able to overcome normative constraints and shift right on immigration and integration—sometimes in draconian fashion—facilitating its electoral success. Likewise in New Zealand in 2017, Jacinda Ardern weathered charges of racism from progressive commentators to campaign on a platform that included cutting immigration levels in half. Ardern won in coalition with the populist-right New Zealand First.

It appears left-wing parties in countries undergoing demographic change face a dilemma. Move right on immigration and risk alienating your activists, or tack left and lose elections. The one major exception to this rule is English-speaking Canada. While Quebec elected the populist-right, anti-immigration CAQ to provincial office in 2019, Canada as a whole returned the Liberal Justin Trudeau to power in the federal election the same year. Trudeau is overtly pro-immigration, post-nationalist, and “woke” on gender, aboriginal, and sexuality issues. Ordinarily, this would be a recipe for failure. So what’s different?

Essentially, English Canada lost its loyalist cultural tradition with the decline of the British Empire, creating a vacuum which 60s progressivism, in the guise of official multiculturalism, was able to fill, redefining Canadian identity. The Anglo-Canadian electorate thereby leans left politically by a 60-40 margin whereas most other western countries are evenly split. However, Canada is undergoing an unprecedented cultural and political polarization. The share of Conservative voters who approve of Justin Trudeau has hovered between just three and six percent since June 2019 compared to 90 percent among Liberal voters as of January 2020. Immigration attitudes differed by only 10-15 points between the Conservatives and Liberals five years ago, but the gap is now around 50 points. This is similar to what I found in the United States between 2012 and 2016 where Republican voters became more restrictionist while Democrats moved in the opposite direction, creating a 50-point divide over whether immigration should be reduced.

The ethnic change that is transforming western societies makes cultural issues more relevant, benefiting the Right while harming a Left that finds itself hemmed in by progressive norms, unable to adapt to new electoral realities.