Liberalism has never had a prefabricated essence ascertained all at once or implemented with a coherent plan.

Breaking the Spell of Marxism

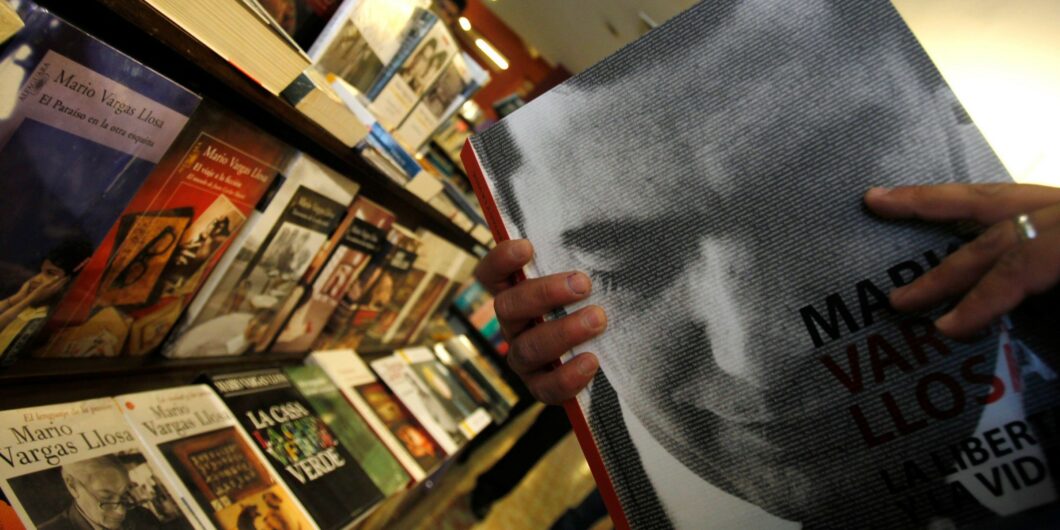

While classic literature provides an inexhaustible fount of wisdom for exploring the complexities of human nature and the human condition more broadly, as a rule the same cannot be said for contemporary writers. Indeed, with their predilection toward mindless ideological clichés and sympathy for revolutionary regimes of the most despotic kind, contemporary writers are perhaps the last place one should turn for political wisdom of a sober, measured, and reliable type. There are notable exceptions, to be sure. The Peruvian Nobel Laureate Mario Vargas Llosa is very close to the top of that list. He is at once a gifted writer and a sensible and humane guide to political judgment. But it wasn’t always so.

In the opening chapter of his engaging political and philosophical reflection, The Call of the Tribe, Vargas Llosa traces his own intellectual odyssey from Third World radicalism and a quasi-religious faith in socialist transformation to a distinctive liberalism informed by the reflection of seven distinguished European writers and thinkers: Adam Smith, José Ortega y Gasset, Friedrich August von Hayek, Karl Popper, Raymond Aron, Isaiah Berlin, and Jean-François Revel. In his thinking and concerns, Vargas Llosa navigates between Latin America, Spain, France, and the birthplace of modern liberty which is Great Britain. His choices will not immediately resonate for those whose concerns and references are narrowly American-centric, but his cast of intellectual guides and heroes are indeed sturdy defenders of civilized liberty from which we have something important to learn.

As a young man and writer, Vargas Llosa was swept up in the abstract “literary politics” (as Tocqueville strikingly called it) of the age. He displayed an unwise attachment to Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution and over the course of a decade “defended the revolution in manifestos, articles, and public works” both in France (where he was then living), “and in Latin America, where [he] traveled quite regularly.” He was under the spell of the Marxisant and fellow-traveling political reflection of Jean-Paul Sartre and his ilk, although he admits to being intrigued by the political sobriety on evidence in Raymond Aron’s weekly column in the Parisian daily Le Figaro. But the Stalinization of the Cuban Revolution and the vicious persecution of the poet Herberto Padilla for speaking his mind about cultural repression in Cuba began to awaken Vargas Llosa from his ideological slumber.

He began to value the so-called “formal freedoms” of bourgeois democracy as a precious protection for liberty and human dignity, and not a cover for the exploitation of the oppressed, as Marxists falsely claimed. With his eyes increasingly opened to the realities of “really-existing socialism,” and his mind now guided by such anti-totalitarian writers as Albert Camus, George Orwell, and Arthur Koestler, the Peruvian writer was on the way to his mature affirmation of a robust anti-totalitarian liberalism. This movement towards a somewhat idiosyncratic and personal version of classical liberalism was reinforced by living in Britain for much of the 1980s, where he was open to the efforts of Margaret Thatcher to reinvigorate economic liberty in a Britain that had turned sclerotic.

At the same time, Vargas Llosa saw Peru sliding into political dictatorship and economic penury under the left-wing regime of Alan Garcia (which had succeeded a repressive left-wing military dictatorship). He actively opposed Garcia’s misguided efforts at full-scale economic nationalization and would run for president of Peru in 1990 as the candidate of the Democratic Front. He stood for economic liberty and the full democratization of Peru. That would entail choice in the educational realm, a reinvigorated rule of law, and an end to the corruption and clientelism that did so much to keep the poor of Peru and elsewhere poor. At the time, Peru was ravaged by nihilistic violence from the Khmer Rouge of Latin America, the fanatical and murderous Shining Path guerrillas. In the 1990 election, Vargas Llosa lost to Alberto Fujimori. To his credit, Fujimori crushed the Shining Path but at the cost of an increasingly authoritarian regime and a good deal of personal corruption.

Vargas Llosa then and now defends liberalism against a Left that opposes it with cheap slogans rather than sustained arguments. He is also at odds with certain elements in the Catholic Church who continue to “slander” the liberal dispensation “despite the existence of so many liberal believers.” This tendency is not, alas, found only in the past. Today, Pope Francis combines the Church’s traditional prejudices against a caricatured “liberalism” with a certain indulgence toward the totalitarian left. Personally, Vargas Llosa himself expresses no deep spiritual yearnings and no obvious sympathy for the Christian contributions to Western civilization, but no open or overt hostility to it either. He is more sensitive to the Christian sources of religious fanaticism than he is to its considerable contributions to the moral foundations of modern democracy. The fraying of this heritage in modern Europe hardly evinces a comment from the Peruvian writer. It is fair to say that he is anti-clerical without being particularly anti-Christian. His Latin American background undoubtedly accounts for at least some of his striking indifference to the religious sources of Western liberty.

Vargas Llosa’s portraits of his seven heroes, his classical liberal pantheon, are well drawn and easily sustain the interest of the reader.

To the Edinburgh Station

Vargas Llosa writes with rare clarity and elegance, and with an admirable energy and liveliness. His portraits of his seven heroes, his classical liberal pantheon, are well drawn and easily sustain the interest of the reader. The Call of the Tribe shows that a work of non-fiction can very much be a work of literary art, written with a precision and grace that carry over perfectly well in translation. His model is the once-famous book To the Finland Station, published in 1940 by the literary critic Edmund Wilson. That book provided an artful (if one-sided) account of the development of European socialism from the nineteenth-century French historian Jules Michelet to Lenin’s terribly consequential arrival at the Finland Station in St. Petersburg in April 1917.

In his book, Vargas Llosa intends to illustrate a counter-intellectual history beginning with Adam Smith’s defense of “natural liberty” tied to moral propriety and culminating in portraits of various anti-totalitarian liberal thinkers who resisted the slide toward collectivism and intellectual conformity in the twentieth century. The book is noble in intent and a pleasure to read. But in two cases, Popper and Berlin, he largely passes over crucial defects in the thinkers under consideration, and in one case, Aron, he ignores the conservative elements in a generally liberal thinker without which his achievement cannot truly be understood or appreciated.

I will avoid giving detailed accounts of each of these artfully sketched portraits. Vargas Llosa gets the essential points about Adam Smith right and rescues him from his posthumous reduction to the status of a proto-professional economist. He appreciates that Smith was above all a “moralist and philosopher” and understood himself as such. The book that mattered the most to him was The Theory of Moral Sentiments, a classic of moral philosophy that he continued to revise right up until his death. Vargas Llosa does a particularly good job of explicating Smith’s crucial idea of “the impartial spectator,” the “man in the breast,” the judge or arbiter who allows us to judge our own conduct in something like an objective or non-arbitrary way.

The impartial spectator may not be the literal voice of God in the human heart as a Christian like Newman thought, but he is the closest thing to Divinity within each human being that Smith recognizes or describes. As Vargas Llosa ably shows, Smith was far from a moral relativist and never wished to liberate the political economy from moral evaluation or judgment. Smith saw himself as a friend of the poor and opposed mercantilism and heavy-handed regulation precisely because they aided and abetted “the monopoly of the rich” and did little to help the truly “poor and miserable.” Smith’s approach to political economy is thus broad and humane and hardly lacking in “sensitivity and solidarity.” Nor was he a closet “progressive” as some strained recent scholarly interpretations would like to suggest.

The chapter on the admirable Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset is of particular interest, at least to this reader. The Anglophone world knows him primarily for his 1930 book Revolt of the Masses, a rich and enduring reflection on the loss of individual moral and intellectual self-command and the rise of a new barbaric tyranny and conformism. It is a book to be read along with Tocqueville and Arendt, and its aristocratic liberalism is a welcome and needed corrective to the doctrinaire egalitarianism of the age. At the same time, Vargas Llosa rightly faults the great Spanish thinker for ignoring the central place of economic liberty in any liberalism worthy of the name, and for hardly knowing or appreciating the considerable moral resources undergirding American democracy. Ortega saw America as “the paradise of the masses,” a caricature at best and a calumny at worst.

Today, especially in Spain, Ortega is viciously attacked by left-wing bien-pensants for refusing to choose between a Stalinizing Republic, on the one hand, and Franco’s Nationalists, on the other, during the vicious Spanish Civil War of 1936–39. Vargas Llosa defends Ortega against these attacks, especially by those who falsely paint Ortega as a closet Francoist and Falangist. But he does so with some defensiveness since the left literati in Spain see “fascism” as the enemy par excellence. But these ideologues are pygmies compared to the civilized liberalism of Ortega, which hardly had a space to breathe during Spain’s terrible ideological polarization in the 1930s. A less apologetic defense of Ortega would have been more courageous and effective.

The Liberal Tradition

The central chapters on Hayek, Popper, and Berlin are not without interest. Vargas Llosa sympathetically lays out the central ideas of Hayek’s 1944 The Road to Serfdom, The Constitution of Liberty (1960), and Hayek’s later writings. These include respect for “spontaneous order” and equality under law, a recognition of the limits of social “constructivism,” and a critique of the ample “contradictions” of the “planned” economy and society. He also criticizes Hayek, with some justice, for tending to lump all “socialists” into the same authoritarian category.

The chapter on Karl Popper nicely describes the Austrian-born philosopher’s movement from youthful socialism to anti-Marxist liberalism. Vargas Llosa is, in my view, rather too sympathetic to The Open Society and Its Enemies (1944). That book effectively defended moderate liberty, but egregiously misread Plato, Aristotle, and even Hegel as precursors of modern totalitarianism. Popper is simply out of his depth in his most famous book. But Vargas Llosa highlights some excellent insights found in Popper’s 1957 book The Poverty of Historicism: a critique of global determinism of the kind espoused by Comte, Marx, and even Mill—a lucid and compelling critique of utopian social engineering in the name of a modest preference for improvements that are incremental but sustained.

Vargas Llosa is right to resist the “call of the tribe” and to denounce fanaticism, tribalism, and intellectual conformity in the variety of its forms.

In contrast, “the piecemeal engineer,” an unfortunate choice of words in my view, “puts the part before the whole, the present before the future, the problems and needs of men and women in the here and now before the uncertain mirage of humanity in the future.” There is much to appreciate in this formulation. On a critical note, Vargas Llosa gently chastises Popper for writing a book near the end of his life in which he argued that television posed a grave danger to democracy and therefore that its influence needed to be curbed.

Thus, at the end of his life, Popper increasingly sounded like the classical political philosophers he had so unfairly disparaged. They, too, had worried about the moral degradation of democracy and the accompanying decline of citizen virtue that came with it. Confronted by the winds of postmodern nihilism, Popper undoubtedly grew more conservative in his final years. How much more appalled would he be by moral and cultural degradation brought about by the omnipresent internet and the intended addiction of handheld gadgets?

Indeed, considerably more than Vargas Llosa, Popper and Aron expressed deep concern about the erosion of the moral supports for the constitution of liberty in the years after the revolutionary year 1968. Even Hayek lambasted Freud for his role in undermining the self-restraint necessary for free men and women to live responsibly in a truly free society. Vargas Llosa seems, however, largely insensitive to these concerns. His liberalism is too “liberal” in the end, and insufficiently “conservative” before the challenge of postmodern moral and intellectual nihilism. The closest he has come is to express his deep concern that our cultural turn to the visual and away from the textual has undermined the patience so necessary for civilized life. About that he is certainly correct.

In this, our author is not unlike his hero, Isaiah Berlin. Berlin, like Popper, was an admirable critic of full-blown historical determinism and twentieth-century totalitarianism. Berlin artfully and eloquently demonstrated the crucial role that the free will of great individuals played in shaping the dramatic events of the twentieth century (see his magisterial 1949 essay “Churchill in 1940”). At the same time, he rested content with a spiritually anemic defense of “negative liberty.” Nor does Vargas Llosa appreciate how close Berlin’s “value pluralism” is to out-and-out moral relativism. Berlin is weak, to say the least, on the essential ties that bind truth and liberty. His English decency, however, ultimately prevented him from succumbing to the radical relativism implicit in a pluralism that gave little or no guidance for weighing and balancing competing goods.

The Peruvian Nobel Laureate is a Francophile who has intimate knowledge of the French intellectual scene. He came to admire Raymond Aron (1905–83) for his immense learning, his immunity to the totalitarian temptation, his refusal to be cowed by ideological fashion, his moral clarity about Communism, and his refusal to celebrate the revolutionary bacchanalia that was the Parisian “May revolution” of 1968. But in an otherwise fine reading of Aron’s 1955 classic The Opium of the Intellectuals, he misreads the import of Aron’s critique of the secular religiosity of the intellectual Left and the duplicity of their progressivist Christian collaborators. Vargas Llosa underplays Aron’s respect for authentic transcendental religion. Aron emphatically stated that his skepticism was not directed at authentic religion itself, but rather at “schemes and models, ideologies and utopias.”

In addition, Vargas Llosa misleadingly claims that Aron saw the great French statesman Charles de Gaulle fundamentally, and finally, as an “authoritarian.” But as Aron’s long-time protégé Jean-Claude Casanova argues in his “Preface” to Aron et Gaulle, a collection of Aron’s writings on the French statesman published in the fall of 2022, Aron acknowledged the French statesman’s greatness, respected him, and saw in him no trace of the tyrant. At the same time, Aron criticized de Gaulle when the circumstances required it, occasionally forcefully, especially in matters related to foreign policy. He however sided unequivocally with de Gaulle in resisting the “elusive revolution” that nearly brought down the French Fifth Republic in May 1968.

Vargas Llosa simply ignores what we might call the conservative side of Aron’s political philosophy. Between 1968 and his death in 1983, Aron expressed grave concerns about a crisis of authority in liberal Europe. Authority was confused with authoritarianism, and civic virtue was hardly to be found when it was not dismissed as outdated and irrelevant. In a posthumously published book called Liberty and Equality, to be published in English later this year, Aron spoke of “the moral crisis of liberal democracy.” He emphatically warned about replacing a robust sense of reality with the “liberation of the pleasure principle.” And he added that “theories of democracy and the theories of liberalism always included something like the definition of the virtuous citizen, or the manner of life which would conform to the ideal of a free society.” Such a concern is missing in Vargas Llosa’s account of Aron and is hardly present in his discussion of liberalism as a whole. That is a significant lacuna, which shows the limits of Vargas Llosa’s own liberalism.

The portrait of Aron is followed by a delightful portrait of Aron’s friend, the French journalist, essayist, writer, and pamphleteer, Jean-François Revel. He was one of the best-informed critics of totalitarianism in the Western world. His prose was impeccable. Revel took on all the illusions of the Left, while hardly being a man of the Right himself. He was a republican in the French secular sense and hardly had a religious bone in his body, although his son became a famous Buddhist monk, and father and son wrote a global bestseller together. Revel turned to liberalism in the Mitterrand years, somewhat belatedly, realizing that democratic socialism was in the end a chimera. As Vargas Llosa rightly suggests, there is no journalist in the Western world today who matches Revel’s pugnacity, courage, panache, and breadth of interests. To his great credit, Vargas Llosa allows us to hear Revel’s voice once again and to truly appreciate his merits.

In his title, Vargas Llosa names his bête noire, the siren call of tribal allegiances. In many respects, he is right to resist the “call of the tribe” and to denounce fanaticism, tribalism, and intellectual conformity in the variety of its forms. But he also exhibits a danger inherent in liberalism, of casting out the baby with the bathwater, or less metaphorically, of failing to appreciate liberty’s preconditions and its culminating aspirations. For example, is humane national loyalty simply a form of tribalism? Does the West, and the constitution of liberty more specifically, not have crucial moral and cultural prerequisites that we are obligated to articulate and defend? These are questions and concerns that come to mind in engaging Vargas Llosa’s eloquent, thoughtful, and lively— but ultimately flawed— recovery of the liberal tradition.