Formerly the world’s bastion of self-government, the United States has become a cesspit of self-love.

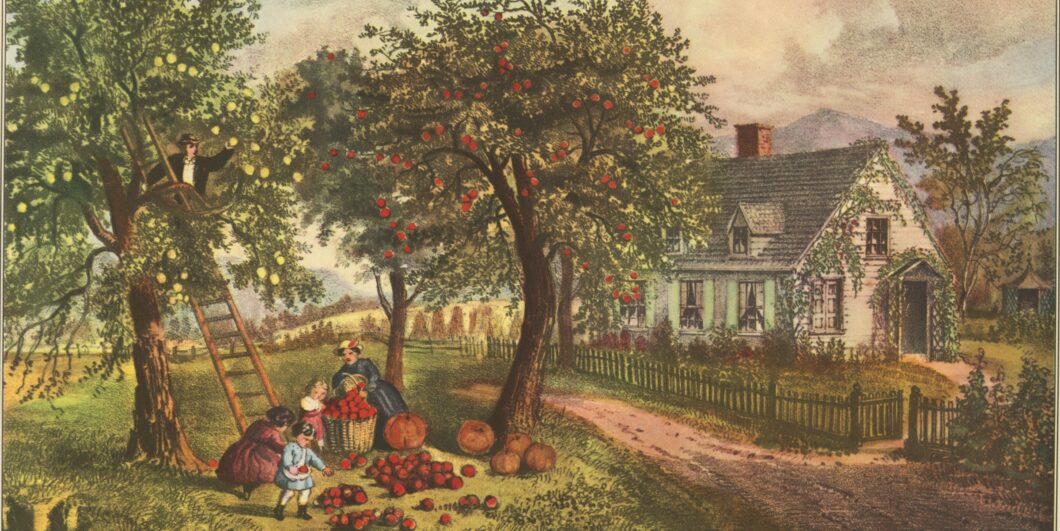

Cultivating the American Life

Several years ago, my wife and I moved to an old stone farmhouse in a rural part of Frederick County, Maryland. In all the time we spent restoring the house and cultivating the land, however, we did not think much about the house’s history. In fact, for a long time we had naively assumed—and erroneously told people—that the house was built in 1847, because that number, alongside the name “Jacob Sponseller,” is inscribed on a drawer in one of the rooms.

Rarely does an academic book resonate with a scholar’s personal life. But it just so happens that this is exactly what happened when I read Bruce Frohnen’s and Ted McAllister’s Character in the American Experience: An Unruly People. As I read the book’s opening chapters on pre-1787 America, I became more interested in the history of my house. After lots of digging and sorting through Frederick County archives, my wife and I learned that the tract of land was first licensed in 1746, and the house seems to have been built in the 1750s. The 1847 “Jacob Sponseller” inscription, it turns out, was likely written by a child—probably a nephew of an owner living here at that time.

Even more astounding to us was the plurality of the owners. The original owner was an Irish immigrant who soon left to explore the frontier of what would become West Virginia. The next two owners were Englishmen who had come from southern Maryland to settle in western Maryland. The next owner, the son of an Irish settler, purchased the house and land in 1795, likely with money earned fighting in the War of Independence. The grandchild of that man married a descendant of Germans who had moved down to Frederick from Pennsylvania. And that woman’s maiden name was Sponseller, which is how it came to be written on the drawer.

So just in its first century of existence, our house had owners of English, Irish, and German descent. But these diverse owners nevertheless had much in common. Indeed, as part of our research, my wife and I read through the owners’ wills, and we noted how the wills began with lengthy expositions of the testator’s faith in redemption through Jesus Christ. We also learned that many of the families attended the church down the road from our house; in fact, many are buried in the church cemetery. And the family names are still found in the region (the neighboring farm is directly linked to the 1795 buyer).

The story of our house is very much the story of Frohnen and McAllister’s Character in the American Experience. America is not a singular nation, with an identity traceable to a particular ethnic lineage. This, of course, could be said about many modern-day states. But America is distinct in how its ethnic differences have animated and fueled its political development, at times, in ways that have threatened the nation but often in ways that have defined and even strengthened it.

Here, it is important to distinguish Frohnen and McAllister’s argument from the pablum that permeates contemporary discourse on American diversity. Frohnen and McAllister do not see America as a “nation of immigrants.” Nor do they believe that America is defined by the idea that “diversity is our greatest strength.” If anything, Frohnen and McAllister view America as a nation of settlers whose European ancestry and Protestant beliefs laid the foundation for future generations of immigrants who would later develop the nation within the culture that the settlers created.

In Chapter Two, for example, “The Roots of American Culture,” Frohnen and McAllister argue that we currently misunderstand the American identity, because we ignore the extent to which “settlers were more important in creating our culture than immigrants.” These early settlers brought the cultural backgrounds from their native regions, but they adapted those cultures to the experience of settling land, in turn “establishing linguistic patterns, religious beliefs, architectural and other material cultural traits, marriage and family structures, and a host of other folkways.”

Instead of turning this into a philosophical matter, as though these early Americans were united by their understanding of John Locke or John Winthrop, Frohnen and McAllister observe that, in the formation of this new culture, “ideas [we]re not necessarily more important than sports, food, clothing, dialect, or class.” The settlers’ folkways were just as important as their notions of liberty in creating the American identity, and “folkways are both deeper and less intellectualized than much of what scholars take as culture.” Indeed, “[h]abits of settlement (whether in towns, clusters of homes, or isolated homesteads), child-rearing, and treatment of the bodies of deceased members of the community” are folkways critical to structuring social and political relations.

Frohnen and McAllister identify four features in particular that united the early Americans: (1) “colonial Americans largely shared English as a common language,” (2) “the vast majority of colonials were protestant,” (3) “Americans lived under and generally admired British law and the common law that underwrote it,” and (4) “the colonials shared a strong attachment to British liberties.”

Frohnen and McAllister trace these four features to “four distinct ‘folkways’” identified by David Hackett Fischer, “each in turn rooted in a distinct region of Britain”: (1) the New England “Puritans from the East Anglia region of England,” (2) the Virginia settlement consisting of people “from a different region of England than the Puritans,” and “from a different class and with different goals,” (3) the Quakers, who settled principally in Pennsylvania, and (4) the so-called “Scotch-Irish” or “Borderlanders” who settled further inland.

Our task is to create and participate in institutions of self-governance that permit—and perhaps even foster—a plural American identity.

These early Americans disagreed sharply on how to structure their social orders. The Puritans, for example, “came with amazing singleness of mind” in “[r]ejecting religious tolerance,” in part because they were “strikingly homogeneous” in their “religious convictions, educational background, professional similarities, family structure, and purpose for migrating.” The Quakers, like the Puritans, “came to America for religious reasons,” but they departed sharply from the Puritans in seeking to create “a society and government that took tolerance and religious freedom as its cornerstone.”

While the early settlers disagreed on the content of rights, as exhibited in the more exclusive Puritans and more inclusive Quakers, they largely agreed on the source in that “they all held dear inherited liberties as their rightful bequests from [their] ancestors.” And even while disagreeing on content, they were unified in that “[a]t the core of their ideals was self-rule.” This ideal, in turn, made the plurality of early America work.

Character in the American Experience is not a polemical work, which is not surprising for anyone familiar with Bruce Frohnen and the late Ted McAllister, both as men and as scholars. But there is nevertheless a perceptible thrust in the book against various currents in American thought on the Founding.

Perhaps most obvious is that the book’s treatment of the American identity is at odds with the progressive version of the story—both in terms of the Wilsonian and New Deal Progressives, as well as our modern-day variety, associated with “wokeness” and the 1619 Project. In Chapters 16 and 17, Frohnen and McAllister document how centralization in the first half of the twentieth century weakened the commitment to “self-rule” that had been so central to the early Americans. In the next five chapters, Frohnen and McAllister explore how this project radicalized in the second half of the twentieth century, principally through the civil rights revolution and the expansion of the administrative state. This, in turn, produced the polarization we see today, the topic of Chapter 23, “Two Peoples, Two Americas?”

These chapters on the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, constituting the last third of the book, have an unmistakable political salience. For example, while Frohnen and McAllister see the African slave experience as an important part of the American identity (covered in Chapter 3), and they fully acknowledge in this chapter that “the most troubling part of our history concerns slavery and a persistent legacy of racism,” Frohnen and McAllister do not see American history as simply reducible to racial oppression, the way that many contemporary progressives do. And while the authors are generally sympathetic to the civil rights legislation (covered in Chapter 19), they are less supportive of the Supreme Court’s civil rights decisions. They also see a dark side to how the civil rights revolution expanded the federal government’s authority over local and private matters.

Character in the American Experience is, however, no mere diatribe against progressivism. Indeed, the nationalist conservative movement is also challenged, albeit less directly, in the book. Many nationalist conservatives, such as Yoram Hazony, imagine the American Founding as creating a monolithic national identity, and they often point to leading Federalists, such as Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, to support this notion. Frohnen and McAllister, however, reveal this idea of a singular American identity to be a fiction, and a dangerous one at that.

The book is just as opposed to treating the American identity as merely ideational, as though America were a “proposition nation,” defined by one line in the Declaration of Independence. This account, popularized by the neoconservatives in the 1980s, is at odds with how Frohnen and McAllister view the Founding—namely, as a product of distinct cultures, folkways, and communal orders. In the neoconservative imagination, the War of Independence was fought on ideological or even philosophical grounds. But as Frohnen and McAllister observe, “[t]he vast majority of patriots fought, not to make the world anew, but to prevent the British parliament from destroying their traditional rights and the institutions of self-government they had inherited and developed in the New World.”

When reading this passage, I was once again reminded of what I had learned in my research on my house. Many of the families connected to the house had fought in the War of Independence, and this was common in the western part of Maryland, because many of the settlers were Scotch-Irish or German (and therefore felt little obligation to the Crown), they were independent-minded as settlers on what was then the frontier, they did not fear the threat of the English presence farther inland, and perhaps most importantly, they were farmers who needed money.

In sum, Frohnen and McAllister warn against reductionist accounts that simplify American history, and in turn the American identity, to monolithic concepts like racism, nationalism, and Lockeanism. Frohnen and McAllister instead encourage us to appreciate and indeed celebrate our complexity and disorder. But that raises a serious problem: If we should think of ourselves as an unruly plurality, how are we to think about the American project going forward?

It may not come as a surprise that, in a book that complicates our understanding of our past, Frohnen’s and McAllister’s prescription for the future is not neat and tidy. There is, in short, no checklist or formula for restoring our order. Indeed, one of the book’s principal themes is that ideology—the systematizing of political problems into formal methodologies—is responsible for creating the deep fissures in American social and political relations. When we start thinking ideologically, particularly in terms of political parties and platforms, we stop thinking of our co-citizens as co-participants in a deliberative process. We instead start thinking of our co-citizens, including our neighbors, friends, and family members, as political enemies to be conquered and transformed.

The authors therefore exhort the reader to focus on living in a way that operates organically outside the parameters of abstract systems or plans. The best way to challenge radical agendas, in other words, is to inhabit a life that exposes their falsehood. Many readers will likely dismiss this as just another localist solution, but I think the authors have something more nuanced in mind. Perhaps it would be more accurate to describe their project as more associational than local in orientation. As Frohnen and McAllister write in the concluding chapter, “[w]hat is needed is a specific kind of self-governing, republican virtue,” which will require “the associations of republican life—the township and its fundamental elements in family, church, and local association.”

In other words, restoring federalism, without the attendant restoration of familial duties, church attendance, and associational freedoms, will not do the trick. This means our task is not simply the negative project of limiting the federal government but also the positive project of creating and participating in institutions of self-governance that permit and perhaps even foster a plural American identity.

This is not the stuff to excite ideologues who romanticize muscular national agendas and who seem more interested in changing the way other people structure their family lives than in how they structure their own. But this inward turn, however dull it may be for those addicted to the rush of reform and revolution, may be the only way to sustain the Republic.

I can think of no better way to honor the legacy of Ted McAllister, and his loyal friend Bruce Frohnen, than to join them in this honorable mission. That is precisely what my family and I plan to do in playing our small part in stewarding the American project on our little homestead.