How the Constitution Unifies the Country

In his splendid new book, American Covenant, Yuval Levin reminds us that the first word of the Constitution is “we.” The Constitution is neither a mechanism, as Woodrow Wilson thought, nor a ploy to thwart majority opinion, as a number of Ivy League law professors think. It hardly runs like a machine. Rather, it creates a framework that makes republican government possible in a massive, diverse, rambunctious country. It establishes hurdles, not barriers, for a majority to overcome. Levin’s key thesis appears in the first clause of the subtitle, “How the Constitution unified our nation.” The second clause, “and could again,” addresses the steps necessary to put the first clause in the future tense. His ability to substantiate the first clause and provide practical suggestions for working towards the second, combined with his lucid, jargon-free prose, renders this book the intelligent reader’s best guide for understanding the American constitutional order, the decay into disorder, and a road toward its resuscitation. Simply put, the Constitution properly understood is the fundament upon which our democratic republic is grounded.

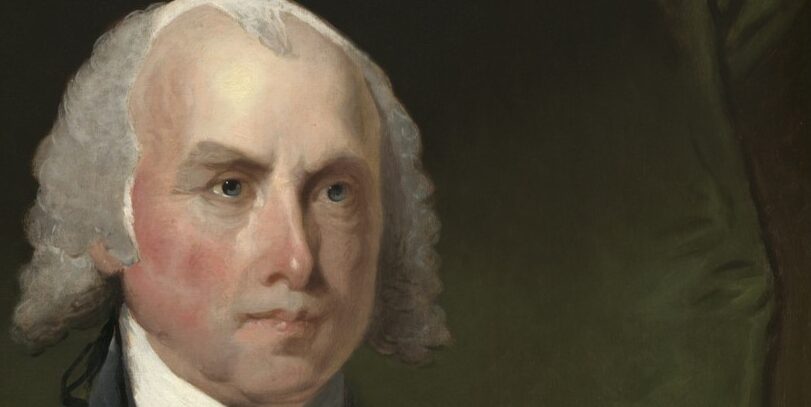

Levin explains that understanding the Constitution is not the exclusive province of lawyers and judges. Indeed, the narrowness of their training hampers them in that endeavor. He urges us to take America’s greatest constitutional thinker, James Madison, as our lodestar. As Madison recognized, a key aim of the Constitution was the preservation and nurturance of unity. Unity does not mean unanimity, although both progressive critics of the Constitution and some National Conservatives seem to think the two words are synonymous. On the contrary, politics in a democratic republic is inevitably riddled with differences of interest and opinion that often result in discord and conflict. Rather, unity means a common attachment to the principles and forms of republican government which enable our society to remain free and intact, despite the rough and tumble of politics.

Levin’s view is reminiscent of the role that the great French political theorist, Bertrand de Jouvenel, accords to government. It is the stabilizer of a dynamic society, the preserver of the “social tie.” As Levin points out, “The Constitution not only gives form to the governing institutions, laws, and political practices of our society, it shapes the American people as well.” It profoundly influences our political culture. As Mary Ann Glendon pointed out in her great book, Rightstalk, Americans love to assert rights claims and pose them against the rights claims of their opponents. As Madison hoped, the Constitution inspires reverence.

To understand the constitutional order, it is critical to recognize that the principle of separation of powers establishes the primacy of Congress. Congress makes the laws and the rule of law is the heart of republican government. The principle of checks and balances is not intended to allow any branch to do the work that another branch has been designated to perform. Despite the inevitable overlaps, Congress makes law; the Executive administers the law, and the Court, as regards public law, interprets how laws already passed and administrative actions already taken should apply to a specific case. “It is only a slight exaggeration to say that Congress is expected to frame for the future, the president is expected to act in the present, and the courts are expected to assess the past.”

Levin sees that the most serious threat to the constitutional order is the urge of the Supreme Court—and the President—to legislate. The Court has gone beyond its authority to interpret the Constitution to declare new rights that the Constitution does not authorize, most notably the right to privacy. Furthermore, it has enabled executive agencies to issue regulations and so-called guidance documents that go so far beyond the intent and the wording of the statute as to substitute their will for the will of Congress. Presidents legislate under the guise of issuing executive orders.

Levin devotes a chapter to each of the powers. For each one, he gives a discerning account of the formative Constitutional Convention’s deliberations and contemporary distortions, while also offering modest suggestions for reform. To encourage the deliberative and compromise-inducing role Congress is meant to play, he proposes loosening the grip of the Speaker and elevating the importance of the committees that purportedly have jurisdiction over the policy area at hand. This form of decentralization is essential for enabling Congress to deliberate in an informed manner. To further increase committee power, he would do away with separate appropriations committees and give the subject matter committees authority over both authorization and appropriations. To prevent the committees from becoming mere fiefdoms of their chairs, the chairs would be elected by the committee members, not appointed on the basis of seniority. Given these more robust responsibilities, committee members would have a stronger incentive to acquire expert knowledge and seek bipartisan support for measures they favor. Thus, they might choose to devote themselves more to legislative craftsmanship and less to virtue signaling. As Madison asserted in Federalist #51, “The interest of the man must be connected to the constitutional rights of the place.”

Thanks in large measure to Washington, Marshall, and Lincoln, the Constitution became embedded in our political culture.

Whereas slavery and the Senate were the issues at the Convention that were the great potential deal breakers, the Executive was the most difficult. There had never been a Republican chief executive and many at the convention feared that such a role was impossible. The doubters finally acquiesced to the establishment of an energetic executive because they realized that the largest republic ever attempted, covering a vast land mass and vulnerable to foreign threat could not exist without one. In addition to his vital national security duties, the framers stressed his administrative responsibilities.

Levin accepts this understanding of executive power even as he decries the expansion of presidential power which he attributes to the Progressives. “His role is not to be tribune of the people or a visionary tyrant but to engender stability and steadiness in a republican polity that always threatens to burst at the seams.” He blames Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson for the development of the president as opinion-maker and visionary-in-chief. He approvingly quotes Jeffrey Tulis, who coined the term “rhetorical presidency”: “Since the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, popular or mass rhetoric has become a principle tool of presidential governance [so that] the doctrine [assumed] that a president ought to be a popular leader has become an unquestioned premise of our political culture.”

“Unquestioned” is too strong, since Taft, Coolidge, Hoover, and Eisenhower do not fit that description. More importantly, attributing the rise of the president as popular opinion leader to the Progressives underestimates the degree to which Thomas Jefferson pioneered the rhetorical presidency. Jeremy Bailey’s seminal work, Jefferson and Executive Power, demonstrates how aggressive Jefferson was in this regard. His preferred method for shaping public opinion was public declarations, like the Declaration of Independence and his two presidential inaugurals. In the first, he declares that the president is the only representative of the public to “see the whole ground” and therefore his vision of the public good must take precedence. In that address, he envisions “a rising nation … advancing rapidly to destinies beyond the reach of mortal eye.” In the second Inaugural, he claims to have fulfilled those pledges. Nor should one ignore Andrew Jackson’s rhetorical exhortation that the president alone is indeed the tribune of the people. And, especially, one should appreciate the visionary rhetoric of Abraham Lincoln. The Gettysburg Address explains that the Emancipation Proclamation was not a wartime expedient but that it heralded “a new birth of freedom.” The Second Inaugural provides a vision of a postwar nation marked by conciliation, not vindictiveness.

Levin’s insightful discussion of the Supreme Court acknowledges the difficulty of interpreting the Constitution. He criticizes the three most prominent contemporary schools of constitutional interpretation. Nobody wants a dead Constitution, but advocates of a “living” one use that term as a subterfuge for imposing their preferred policy preferences. Levin is devoted to the Framers, but he is not a doctrinaire Originalist. He understands that discerning the intent of the framers is not reducible to linguistic detective work. Nor does he think serious constitutional issues can be settled by a resort to a self-evident understanding of the common good as contemporary natural right thinkers use that term. There are simply too many divergent and conflicting visions of the common good. Rather, the constitution’s claim to unity rests on a political not a strictly moral, conception of the common good—a common commitment to democratic republican government and to the key tenets of the Declaration and the Constitution that sustain it.

Levin recognizes that classical liberalism is central to the American constitutional order. However, liberal principles alone cannot sustain that order. To do so depends on “a set of preliberal and prerepublican institutions of formation—familial, communal religious, civic, and educational. The Framers recognized that the national government was ill-suited to nurture such virtues. It still is. Does the Department of Housing and Urban Development really sustain community solidarity? Does the Department of Education really promote civic education? The genius of the Constitution is to enable those crucial virtues to be nurtured elsewhere. Churches can flourish because the First Amendment protects religious freedom. Members of the public can learn both the rights and duties of citizenship because that amendment protects their right to speak freely and to assemble. States retain the police power, meaning that they make the law that pertains to families, schools, order maintenance, and disputes between neighbors. In practice, states devolve much of the police power to localities, which are the best places for nurturing citizens. Thus, federalism is best viewed as a key element of the separation of powers, providing the proper sphere for sustaining the prerequisites that liberal, republican, government requires.

As much as I appreciate the subtitle of this book, I like the title even more. Perhaps Moses and John Winthrop would not agree, but the Constitution is a covenant. It binds Americans in a way that a contract never could. It reads like a contract because initially it was ratified as a contract. And like a contract, it is amendable and can be rewritten by a constitutional convention (perish the thought!). But contracts do not engender reverence. Thanks in large measure to Washington, Marshall, and Lincoln, the Constitution became embedded in our political culture, though it risks being disinterred. As Yuval Levin masterfully demonstrates, it provides the foundation on which our democratic republic rests.